The Government of India launched the Production Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme to incentivize domestic manufacturing. Its current version seeks to incentivize firms with 6% to 2% of incremental sales over five years, on meeting certain pre-defined investment and sales thresholds. It has become the default instrument of India’s industrial policy.

I have blogged earlier on the PLI scheme here. There’s a risk of the PLI scheme becoming a one-size-fits-all solution to a very complex problem. Let’s start with the problem India’s industrial policy is trying to solve.

If it’s to incentivise domestic manufacturing, it immediately begs the question, how? In theory, a domestic manufacturing base could emerge from a large cohort of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) or a few big firms. In the former, industrial policy would target support for SMEs and try to ensure that a few grow into large firms. In the latter, industrial policy would explicitly support a handful of big firms to grow into bigger sizes.

In reality, given the unbundled and globalised value chains across manufacturing and the importance of economies of scale in achieving global competitiveness, large firms must be given primacy in any theory of change on domestic manufacturing. Only large firms can justify making the investments required to operate at the productivity frontier in their respective industries. The large firms, in turn, encourage the emergence of networks of suppliers, who are more likely an ecosystem of SMEs. This also results in technology diffusion and industry-wide productivity improvements.

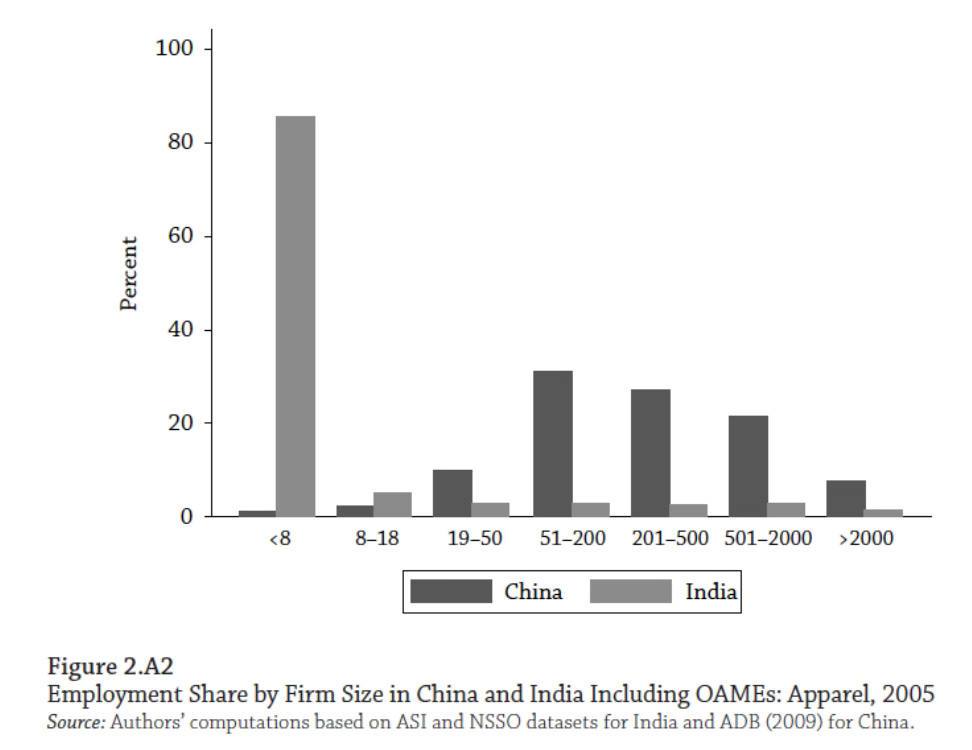

This is especially important given India’s chronic deficit of scale manufacturing and excessive concentration of small firms. This graphic from a tweet is especially relevant, in so far as it points to the stark contrast in firm-size distribution between China and India in the Apparel industry.

If we accept this argument, the objective of India’s industrial policy should be to facilitate the emergence of a few large and globally competitive manufacturers in important industries. I had blogged here making the case for supporting large investments. This should then become the primary objective of the PLI scheme.

North East Asia’s economic success, which Joe Studwell has so brilliantly articulated, was built on a few globally competitive large firms and their cohort of SME supplier networks in each industry conquering export markets. There are some important features of their economic successes that could serve as insights for India as it strives to expand the base of its domestic manufacturing:

1. Industrial policy revolved around export competition. Firms were incentivized to produce for exports.

2. Industrial policy was dynamic in so far as it allowed competition to play out, and confined support to the succeeding firms and allowed the weaker firms to fail. As the Chinese saying goes, “grasp the successful, and let go of the weak”.

3. Instead of spreading scarce resources thin and supporting all firms, this also meant that industrial policy doubled down on supporting successful firms, letting them grow into large firms with massive manufacturing capabilities. The theory of change was that only large manufacturing facilities can create the component ecosystems, maximize productivity, and result in technology and learning spillovers. Big, and not small, was beautiful.

4. A complementary policy focus was to identify a few important and large import volume and value product categories and prioritize support to boost their domestic manufacturing. This too helped avoid spreading the butter thinly.

5. Another aspect of the dynamic nature of the industrial policy was to continually tweak policy to incentivize firms to move up the value chain. Start with assembly and packaging, but then shift upstream to component manufacturing (e.g., in electronic products start with other components and only then move into the semiconductor chips), and then the complete manufacturing cycle.

6. In an acknowledgement of the globalized nature of the supply chain and the gradual nature of the shift up the value chain, import duties were kept low on components to ensure the competitiveness of final export products.

Studwell’s excellent book is only just one source that articulates the centrality of these principles in the region’s spectacular export-led economic success.

India could emulate the East Asian model and orient its PLI scheme in that direction. A few suggestions in this regard:

1. Promote export competition by making in India for the world. In particular, avoid being entrapped in the sub-competitive world of making in India for India. Either mandate a minimum export threshold or provide a differentiated higher level of incentive for exporters.

2. Instead of spreading the butter thin, limit fiscal incentives to only the high value/volume or strategically important product imports in a few sectors.

3. Identify a few firms (say, the succeeding firms from the first round of PLI) in an objective enough manner, and double down on incentives and facilitation for a long enough time to help them grow big. As a corollary, it’s equally important to be explicit about letting go of the support for the weaker firms. This means PLI should be aimed at large companies to facilitate scale manufacturing (including their component manufacturers).

4. Shift away from incentivizing sales to incentivizing domestic value addition, and also increase the magnitude of incentives provided for higher shares of domestic value addition.

5. Lower the customs duties on components of those products prioritized for PLI support. The duties can be raised gradually as a complementary lever to proportionate increases in the domestic value addition thresholds of the corresponding products.

The support for large firms should be complemented with efforts (another scheme) to support SMEs in component manufacturing for the anchor firms. The level of support required for component manufacturers might be higher and is perhaps best achieved through investment subsidies.

Two cross-cutting requirements should accompany these principles.

a. Create a rich database with details of the market trends on production, sales, exports, imports, etc., in each market segment identified for PLI. It can be invaluable decision support in identifying winners, letting go of the weak, tweaking policy, fixing incentive rates, and generally monitoring for the realisation of scheme objectives.

b. Announcing the intent and policy pathway, captured in the aforesaid principles, in a policy document is necessary to signal predictability and shape long-term market expectations.

No comments:

Post a Comment