The conventional wisdom on firm size in India is that labour regulations on hiring and firing (specifically the Industrial Disputes Act, IDA) hinder its growth. I have blogged here and here pointing to research that raises doubts about this argument and here pointing to the importance of the lack of entrepreneurial appetite and dynamism as a contributor. My co-authored paper here dwelt extensively on the problem of firm size and productivity. This post will discuss the issue.

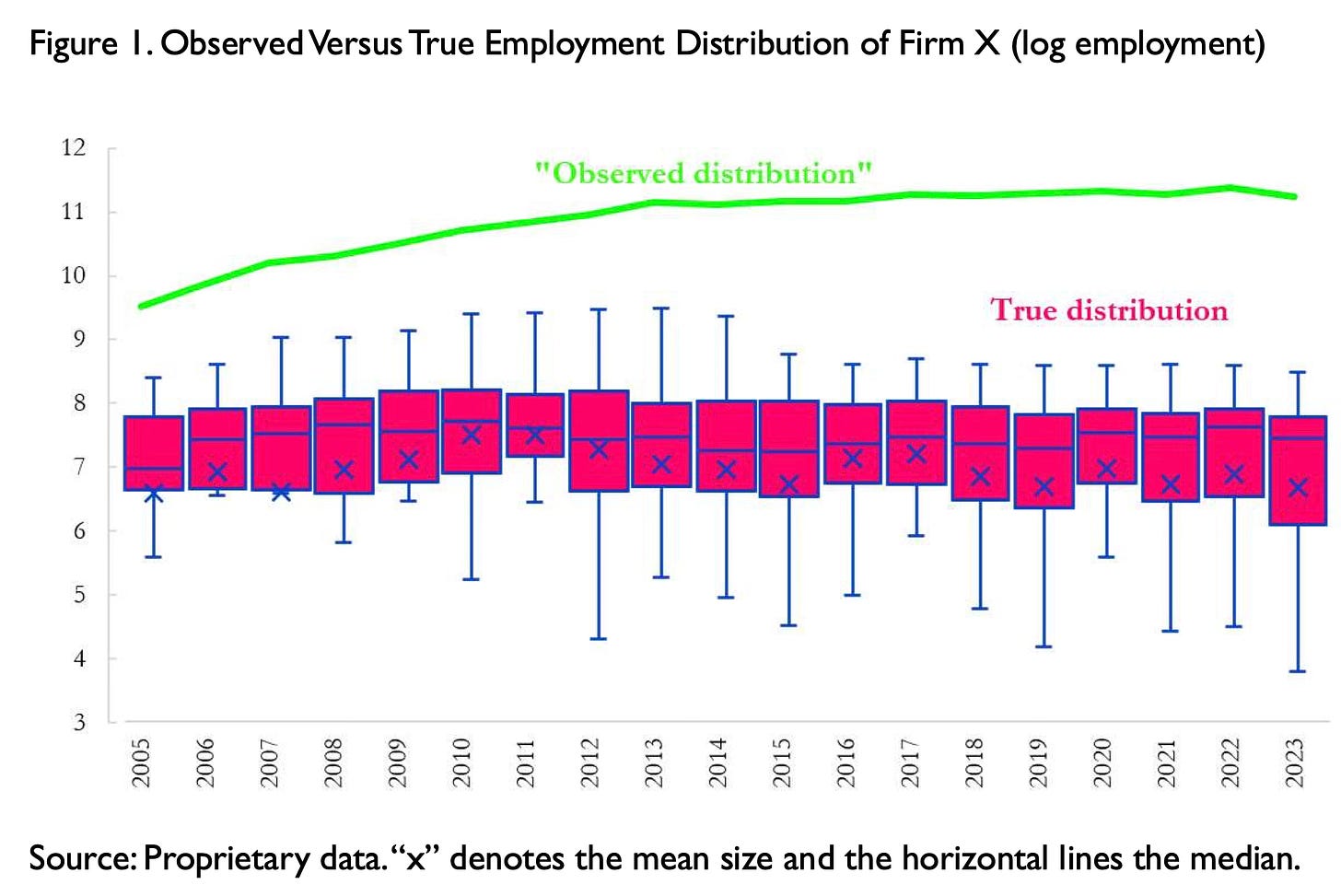

Abhishek Anand, Arvind Subramanian, and Naveen Thomas have a paper with some useful quantitative insights on firm-size. They show that the real problem is not the IDA, large plants are more productive, and that there are very few large globally competitive plants. These are already well-known facts, though not the reasons and the paper does little to explain them. But the contribution of the paper is to draw attention to a flaw on how the ASI data on firm size is captured which might be overestimating the firm size distribution in India.

For documentation of the numbers, I’ll extract some of their findings. These are the three headline findings.

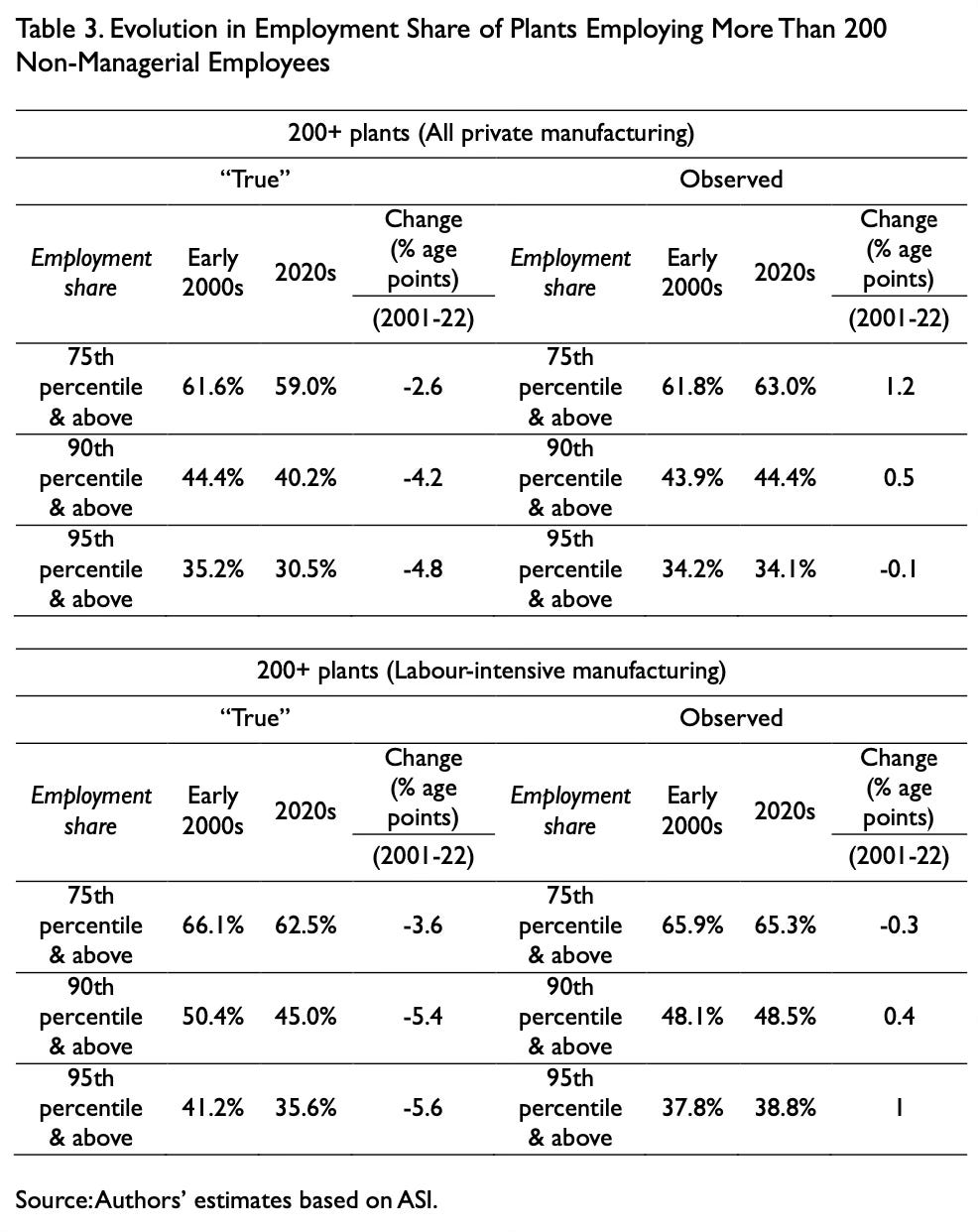

First, that this phenomenon of multi-plants has been growing over time and is quantitatively significant, accounting today for over 25.16 percent of total employment in all plants and 35.48 percent of employment in large plants. Second, ignoring it leads to over-stating the change in the size of plants since the early 2000s. It is popularly believed that Indian plants have become larger but we show that that is not the case and on some metrics large plants may have even become smaller… Third, that the multi-plant phenomenon seems to be a response to some underlying friction. It seems to be an endogenous device for Indian capital to keep their operations small, presumably as a way of coping with the regulatory burdens and risks imposed not, or not just, by labor laws but the broader political environment, shaping capital-labor relations.

Some other findings

The contract labour phenomenon is much greater—almost twice as large—in single plants compared to multi-plants… Single plants are both more “productive” than multi plants for any given level of employment and this differential increases as employment size increases. For example, at employment of 200 workers, single plants are about 9 percent more productive and at 1000 worker plant size, that wedge increases to over 21 percent… even in 2022, the 75th percentile plant in India employed about 53 workers, and the 90th percentile firm employed 128 workers. These cannot be considered large by any means…

Bangladeshi plants export on average 95 percent of their output compared to 37 percent for India… if we compare plants size in India and Bangladesh, we find that Bangladeshi plants are consistently bigger at every threshold with the size differential rising as we go to higher thresholds for size: for example, the 95th percentile firm in Bangladesh is about 40 percent larger than its Indian counterpart… Plants employing more than 200 workers account for roughly 85 percent of all employment in Bangladesh. In India, the comparable correct number is 50 percent. And plants employing more than 1000 workers account for roughly 41 percent of all employment of Bangladeshi plants. In India, the comparable correct number is 15 percent.

They also write on labour regulations

Much of the literature on employment size has focused on the Industrial Disputes Act (IDA) and on examining whether the thresholds in them have shaped plant size. This has been a distraction, impeding our understanding of plants size and the labor market… We find that there is a clear tendency for plants to remain small even beyond the 100 worker threshold set in the IDA so that it is not the law per se (which is after all legally irrelevant beyond the threshold) but other factors that shape firm behaviour.

The authors also discusses how labour hiring and management decisions may interact with the firm size, but different from the conventional wisdom on the restrictions of the IDA, in a two-part oped here and here.

Rising contractualisation of labour — from about 22 to 41 per cent over the first two decades of this century — has been an important response of Indian firms and their management to the regulatory environment. Firms such as TeamLease act as brokers, taking upon themselves the burden of complying with labour laws so that manufacturing firms themselves do not have to. But somewhat puzzlingly, we find that contractualisation is lower in labour-intensive industries than in non-labour intensive ones. This is puzzling because if contractualisation is a response to labour laws and their burdens, the incentives to do so should be greater in labour-intensive industries. For example, in labour-intensive industries, the share has risen from about 23 per cent to 31 per cent over two decades, but in other industries from 19 per cent to 47 per cent. Unpacking this further, we find that recourse to contractual labour is greater in single plants than multi-plants. We also find that at the margin, the incentive to substitute contract labour for full-time employees rises with employment size in single plants but does not do so uniformly for multi-plant units.

One explanation is simply that in multi-plant units, flexibility in hiring and firing labour comes from the fact of having many plants. In single plants, there is no such flexibility, which renders the use of contract labour more important. We were told by the CEO of a large exporting firm that in the event of, say, a drop in orders from one client that affects one plant, the firm can redeploy labour in another plant without having to terminate their employment, which would be the only option in a single plant establishment. In other words, multi-plants and contract labour are both devices that increase flexibility but in different ways and for different situations and work as substitutes. According to the CEO, it would be more competitive internationally if its plant sizes could be greater. But it chooses not to grow as a matter of diversifying policy and legal risks and because of onerous regulations.

The risks may not be the law per se but stem from the broader political environment in which the firm feels it would be vulnerable to the whims of the Centre and state governments, and also to labour in the event of frictions or disputes. A dispute in a big plant would entail greater risks relative to that in a smaller plant: In an extreme situation shutting down a plant with 500 employees is less costly than one with 5,000 employees… The constraints imposed by the thresholds in the Industrial Disputes Act are not the only deterrents to scaling up; it is the pervasive uncertainty in the business and regulatory environment that seems to compel firms to fragment their operations regardless of scale.

The conventional wisdom on firm growth in India is that they are constrained by labour laws that discourage expansion beyond certain employment levels. While there’s some truth in this, there are other (perhaps more difficult to overcome) glass ceilings that Indian firms encounter in their growth trajectories, that go beyond even the political and regulatory risks imposed by labour size alone in a plant.

While the paper discussed above goes beyond the narrow instrumentality of the labour hiring and firing constraints posed by the IDA, and points to the uncertainties in the country’s political and regulatory environments that deter labour expansion, the problems may go much deeper.

Large size is not just about labour. Let’s explore this a bit more. A few questions are in order.

Is it the case that instead of some unique Indian contextual reasons, the very nature of the political and regulatory risks of large plant size by itself, irrespective of the country but especially so in developing countries, are too onerous as to discourage firms in general from establishing large plants? Is it possible that the large manufacturing plants, of the kind we are interested in, emerge only through special circumstances (and not through the general market dynamics of demand, competition and firm growth)? Is it possible that irrespective of the general political and regulatory environment, such large-sized factories can emerge only through proactive support from the government? Is it the case that governments in India while not explicitly against large size have not been active promoters of large-sized plants in particular and large firms in general, preferring instead to support small and medium-sized firms?

There’s nothing automatic or market-based about the growth of successful firms from small to medium, and from medium to large, especially in the manufacturing sector. Firms hit binding statutory, economic, and entrepreneurial constraints when they reach a certain size. For example, as I blogged here and here, there might be significant risk-appetite bounds to be crossed in such transitions, which many, if not most, successful entrepreneurs struggle with.

Apart from the political and regulatory uncertainties relating to labour discussed above, large size is associated with generally more onerous compliances, firm growth requires adding new factories, hiring good professional executives besides expanding the labour force, revisiting ownership holding and corporate form, changing management structure and practices, tweaking business models, acquiring new customers, assuming more debt, etc. Firm size also invites greater external scrutiny of all kinds in general. Each of these imposes significant requirements on the owners and the management, including decisions that require overcoming entrenched norms.

For example, many successful family-owned firms struggle to trust professional executives and prefer to avoid assuming more debt. The smaller size of the enterprise helps them control their business without relying on outsiders and professional managers. It also limits the commercial risk exposure from a business downturn. They can rely on some local and loyal staff to manage the business. Scaling also requires investments in greater automation and adherence to greater standards, which demands capital and debt. All this creates the danger of losing control and assumption of greater business risks.

Further, as firms become large, they must compete with their more aggressive national and foreign competitors to acquire and retain customers and iterate continuously to improve their products, business lines, and delivery models. Any growth that involves expansion into foreign markets demands continuous productivity improvements, agility, and a high risk appetite. The firm cannot stay static and must be dynamic in all aspects. All this requires a growth mindset - an appetite to assume risk and an ambition to expand and become an industry leader. However, most Indian firms appear happy and content with their current market share, at best growing marginally, and strive only to retain it. The low R&D investments of even the leading corporates in the country are a reflection of this mindset.

The growth bounds are perhaps amplified for Indian entrepreneurs with their struggles of doing business in environments that are sometimes downright hostile and mostly not-so-easy. These constraints manifest in the general inability of large numbers of very good small and medium enterprises to break out and emerge as large-scale firms.

So what are the policy takeaways to address this complex and binding constraint?

A headline takeaway that should be strongly internalised among policymakers in India is that scale manufacturing does not emerge on its own and requires government support. This is important since the current guidances and norms are not only to support SMEs but also to avoid supporting larger firms. There are some other misplaced but widely held beliefs, amplified also by the fear of vigilance agencies - once the SME grows the industrial policy support should cease, and firms once supported must not benefit again etc.

It must be noted that government support has been central to the emergence of scale manufacturing in China and all the North East Asian economies. The zaibatsus and chaebols of Japan and South Korea respectively created the culture of world-class scale manufacturing in those countries, with considerable support from their governments.

The likes of Morris Cheung of TSMC and Grace Wong of Luxshare Precision Industry got extraordinary levels of support from the governments of Taiwan and China. Thanks to the support the Chinese government provided to help her company emerge as a leader, the latter has in a little over a decade emerged to become Apple’s second biggest supplier, coming only behind her previous employer Foxconn. The government virtually forced Apple to enlist and grow Luxshare as a contract manufacturer for Apple products. The Chinese government has focused on the creation of large-scale manufacturing giants, especially but not only among state-owned enterprises.

A general feature of the successful North East Asian industrial policy has been to weed out the weak and double down with support for the strong firms and let them grow in size.

A big positive about India’s scale manufacturing strategy is the arrival of large foreign contract manufacturers and domestic corporate groups like Tata. These were perhaps the only ways scale manufacturing could have emerged in India. Tata has taken the lead on electronics manufacturing in India, with active government encouragement and PLI and other facilitation support by central and state governments. It’s incumbent on the other large conglomerates with manufacturing legacy to step up and emulate their East Asian counterparts and establish scale manufacturing facilities.

It would now be interesting to closely study at least three possible future trends over the coming 5-10 years. One, are these large contract manufacturers spawning a large and growing ecosystem of component manufacturers and sub-assemblers in India? Two, is the initial cohort of contract manufacturers engendering emulation by domestic corporates and entrepreneurs, especially those with existing medium-sized firms in the industry? Three, is the presence of large contract manufacturers resulting in knowledge and technology spillovers across the regional economies and contributing to productivity improvements?

I can foresee one important problem with the realisation of these objectives. The aforesaid trends require significant AND increasing value addition by the contract manufacturers. It provides the market signals of market and value-addition growth to both foreign component manufacturers and those dynamic and ambitious domestic entrepreneurs to set up shop. Firms look for growth both at the extensive (volume of the same business) and intensive (increasing value addition and shift to adjacent market segments) while making long-term investment decisions. It’s possible that the contract manufacturers, especially but not only the foreign ones, could largely remain stuck in the lower-value assembly stage and not have the incentives to continually move up the value chain.

It’s therefore important that public policy closely watch the emerging trends and engage to achieve the objectives above. The current success in mobile phone assembly should not blind us to the need to quickly move up the value chain by doing more component manufacturing domestically.

The PLI scheme is a good place to start. The next round of PLI-scheme incentives could be linked to domestic value addition as against sales (even with all the challenges of its accurate measurement). It may even be useful to consider extending the incentives on the existing PLI scheme beneficiary firms for another five years, but this time on the incremental value addition over a baseline. There should not be any limits on the number of times a firm can access PLI scheme benefits (in the different scheme rounds).

These and other policy interventions might be necessary to achieve the objectives underlying the three aforesaid desirable trends.

No comments:

Post a Comment