I have blogged on multiple occasions (this and this) that the biggest challenge to the social contract from widening inequality comes from the consequent inevitable capture of the political processes and the rules-making institutions.

Jeff Bezos and Amazon are only the latest examples of how this capture plays out. Here are two illustrations from recent newspaper reports.

It has just been reported that as the owner of the Washington Post, Jeff Bezos, has intervened to prevent the paper from endorsing any candidate in the US elections for the first time in 36 years.

The newspaper’s editorial page staff had written an endorsement of Kamala Harris for US president, but it was not published following a decision by Bezos, the Post’s owner, to change its policy on endorsements, according to an article in the paper... Sir Will Lewis, The Washington Post chief executive, outlined the reasoning behind the policy change in an opinion article in which he acknowledged that it could be read as “an abdication of responsibility” but added: “We don’t see it that way.” However, the newspaper’s guild said the decision raised concerns that “management interfered with the world of our members in editorial”... This will be the first time that the Post has not endorsed a president since 1988... Lewis, a former executive at News Corp and The Telegraph, was appointed by Bezos last year to try to arrest mounting losses and a decline in readership. People close to Lewis have said in the past that he is in regular contact with Bezos, and would not make big decisions without his input... This summer, Lewis angered Washington Post journalists after replacing the executive editor and other staff with his former colleagues from The Wall Street Journal and The Telegraph. He faced investigations from rival newspapers — as well as his own publication — into his role in a phone hacking scandal in the UK while he was a senior executive at Rupert Murdoch’s media empire. The turmoil at the Post came as Murdoch’s New York Post endorsed Trump for president, with a front-page headline declaring that the “choice was clear”... The Post’s reversal on endorsements follows a decision by Patrick Soon-Shiong, owner of the Los Angeles Times, to block an endorsement of Harris. Mariel Garza, the editorials editor, resigned in protest.

At a time of deep social polarisation, digital media-induced perversions of public debates, and the rise of populist politics, corporate takeover of media is a matter of big concern. Apart from the disturbing political consequences of such interferences, there are the motivations that drive such decisions. Sample this.

The Associated Press reported that hours after the Post announced its endorsement decision, Trump greeted executives from Blue Origin, the space company owned by Bezos that has a $3.4bn contract with Nasa to build a spacecraft to carry astronauts to the moon and back.

There would be a temptation to weigh in on the issue by arguing that the media should stay neutral and not endorse any candidate, and to that extent, Bezos is right. While that would be a logical (and correct) argument in many political contexts, it would be a disingenuous abstraction from the context in this case.

In the US, it's common to see even people like academicians flaunting their political affiliations. In this milieu, newspapers have been ideologically aligned to political parties and, therefore, have historically endorsed Presidential candidates. The increasing flock of corporate media outlet owners like Jeff Bezos are using their ownership position to interfere in editorial decisions to favour their corporate and financial interests.

And since the interests of corporate owners on a few issues (taxation, anti-trust, widening inequality etc.) are divergent from the wider public interest, such capture of the Fourth Estate has the potential to erode an already fraying social contract further.

The second exhibit concerns carbon emission reduction. Being very large consumers of energy through their data centres and AI algorithms, Amazon and the Big Tech companies are keen to burnish their green credentials by hitting their net zero targets quickly and cheaply. An alternative to actually hitting the target is to manipulate the target itself and the means of hitting the target. This would involve lowering the standards and providing flexibility in measurements. The way emission reduction is calculated offers an opportunity to indulge in greenwashing.

Consider this.

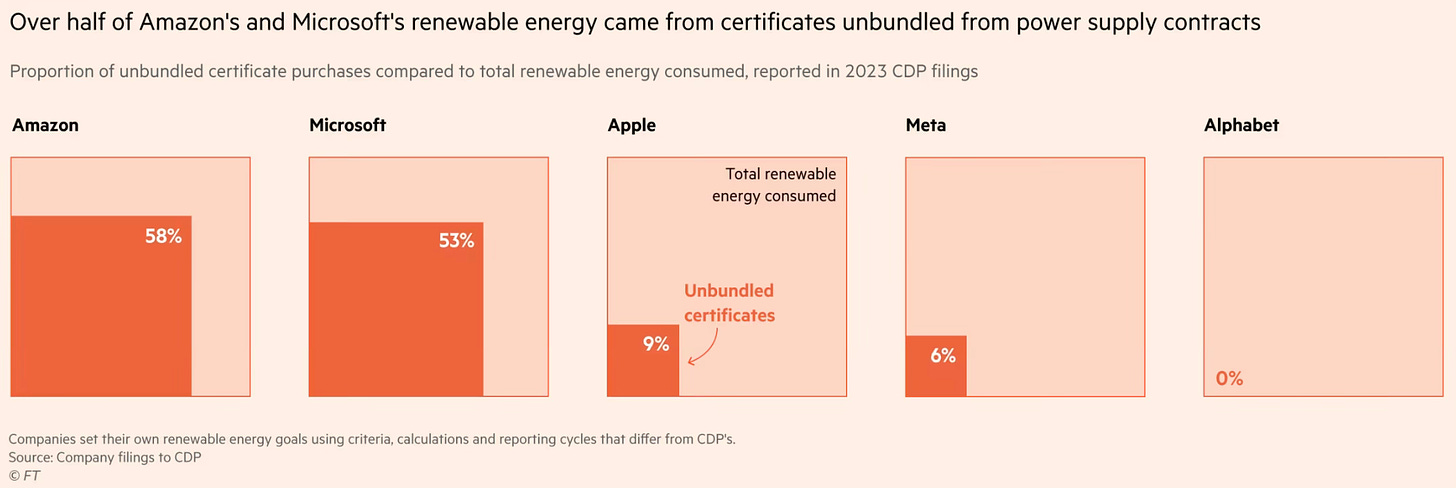

Social media group Meta, for instance, says it has already hit “net zero” emissions in its energy usage. But FT analysis of its 2023 sustainability report shows that its real-world CO₂ emissions from power consumption the prior year were 3.9mn tonnes, compared to the 273 net tonnes cited in the report… Companies including Amazon, Meta and Google have funded and lobbied the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, the carbon accounting oversight body, and financed research that helps back up their positions…A coalition that includes Amazon and Meta is pushing a plan that critics fear will allow companies to report emissions numbers that bear little relation to their real-world pollution and not fully compensate for those emissions. One person familiar with the reform discussions describes the proposal as “a way to rig the rules so the whole ecosystem can obfuscate what they are up to”… A rival proposal by Google, which would require companies to offset their emissions using power generated by more closely comparable means, has been criticised by the Amazon coalition and others for being expensive and too difficult…

Tech companies invest in renewable energy but they cannot fully control how polluting the power their data centres draw from their local grid is. So under current accounting rules, the power used by a data centre during the night in a coal and gas heavy region such as Virginia can be cancelled out by buying a certificate tied to solar energy produced during the day in a region with a cleaner grid, such as Nevada… Each time a wind, solar or hydroelectric facility generates a unit of clean power, its owner can issue an energy attribute certificate, typically known in the US as a renewable energy certificate, or REC. These can either come “bundled” into a contract for clean power, or can be bought individually from a generator or market intermediaries. Companies can purchase RECs “to buy-down their environmental impact”…

But Matthew Brander, a professor at the University of Edinburgh, says the system is akin to buying the right from a fitter colleague to say you have cycled to work, even though you arrived by a car that runs on petrol. Other experts have raised concerns about how RECs are being used to offset real-world emissions. At present, the certificates must come from the same defined geographic region as the pollution they are offsetting, such as Europe and North America, but not the same grid and not at the same time. That means the clean energy that offsets the emissions could be generated in a different country, at a different time of day — or even in the past…

But both timing and location matter in terms of real-world emissions. For example, one potential buyer hooked up to a coal-dependent grid and another on a much cleaner grid could buy the same certificate to offset one megawatt hour of power use — even though the emissions stemming from that usage will differ in each grid. The certificates are also very cheap. The average forward price of a single US renewable energy certificate to be bought in the next calendar year has been under $5 since at least 2022, commodity trader STX Group estimates… Academics and experts at Princeton, Harvard and the Greenhouse Gas Management Institute have shown that buying certificates typically did not drive either a new supply of renewables or a fall in emissions… Google’s proposed solution is to only match energy consumption with clean energy and certificates from the grids where power is consumed, and to take the time of day of its electricity use into account. Using certificates from one area while operating in another could allow buyers to understate their reliance on fossil-based electricity without addressing the emissions for which they’re physically responsible.

In this context, it’s disturbing that Jeff Bezos’ $10 bn charitable group, Bezos Earth Fund is trying to influence the operations of the carbon credit market to allow Amazon to dilute its emission reduction obligations. Amazon is lobbying to not only continue recognising carbon credits purchased from a different geography and time, but also get a higher credit for those purchased from a dirtier developing country grid than from a cleaner developed country grid.

The Bezos Earth Fund is among the largest funders of the Science Based Targets initiative, a globally-renowned body relied upon by groups such as Apple and H&M to set voluntary standards and strict limits on the use of carbon credits to offset emissions… The SBTi is also in the middle of a process of rethinking its approach to offsets, a decision that could prove crucial to Big Tech groups at a time when artificial intelligence is resulting in a leap in emissions caused by the greater use of data centres. Experts and campaigners have grown concerned about the potential of Amazon and the Bezos fund… to influence SBTi, which holds sway over whether many corporate groups can achieve a credible “net zero” label… a former SBTi staff member raised fears about perceived influence of the Bezos fund on climate standards in a July complaint to the UK charity commission. The fund has also financed the organisations that employ three SBTi board members…

Grant-making organisations with current or historic ties to big business, such as Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Ikea Foundation or the Rockefeller Foundation are the financial bedrock of the climate standard setting and campaigning space. Google and its philanthropic arm have also funded bodies in this space. But the battle over the future of the SBTi could prove crucial to corporate efforts to achieve climate goals. Some companies have become frustrated at SBTi’s restrictions on the use of credits to just 10 per cent of emissions… The Bezos fund is also a backer of the top standard setter in carbon accounting: the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which is also in the process of reconsidering its approach to offsets… Amazon is also seen as promoting alternatives to the SBTi’s standards… Amazon last year also contributed to the creation of a market label, Abacus, to test the quality of carbon credits… Buying credits is typically much cheaper than cutting supply chain emissions, making them a tool of choice for some chief executives in the face of pressure to keep climate promises made to shareholders.

There’s a real danger of green-washing here, to fake net zero.

Here’s the problem. The two examples are only the latest to show that wealth brings outsized influence in the political and rules-setting process, thereby eroding democracy and the social contract itself. It’s Jeff Bezos’ outsized wealth that gives him the power to exercise such influence on a terrain that goes far beyond his business or even industry. It’s not possible through any institutional restraint or safeguards short of outright prohibitions (against, say, corporate ownership of media outlets) to insulate from elite capture.

But, even such measures are likely to be blunt given the staggering magnitude of wealth concentration and the availability of instruments to exercise influence (electoral funding, ownership of media outlets, philanthropic foundations etc.) that allow the likes of Bezos to manipulate the political process from behind the scenes (though the likes of Elon Musk no longer make have even these pretensions) to suit their interests.

The final word on the issue should go to this quote from Justice Louis Brandeis (HT: Matt Stoller), who famously said, "We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both." Just as business concentration and competition cannot co-exist, democracy and wealth concentration too cannot go together!