The US stock markets are on a tear. Even the news of “higher for longer” interest rates doesn’t deter it.

There’s a clear theme in the spectacularly persistent boom - artificial intelligence (AI). Nvidia has been the standout leader. This post will examine some of the thinking around the stratospheric rise of Nvidia and the AI-rally in the US equity markets. What’s driving this market expansion? Is it similar to the dot-com bubble? Is Nvidia the new Cisco?

Consider these numbers about the market in the aggregate,

Torsten Slok, chief economist at private equity group Apollo, said the index is looking “more vulnerable”. The top 10 companies in the S&P 500 make up 35 per cent of the entire value of the index, he noted, but only 23 per cent of earnings. “This divergence has never been bigger, suggesting that the market is record bullish on future earnings for the top 10 companies in the index,” he wrote. “In other words, the problem for the S&P 500 today is not only the high concentration but also the record high bullishness on future earnings from a small group of companies.”

… Charles Schwab points out that only 17 per cent of stocks in the S&P 500 have outperformed the index itself over the past year. For the Nasdaq, it is just 11 per cent. “The dramatic outperformance of a small handful of stocks at the very upper end of the market capitalisation spectrum has greatly flattered index-level performance among cap-weighted indexes,” wrote analysts Liz Ann Sonders and Kevin Gordon at the retail broker. “There has been a tremendous amount of churn and rotational corrections occurring under the surface.”

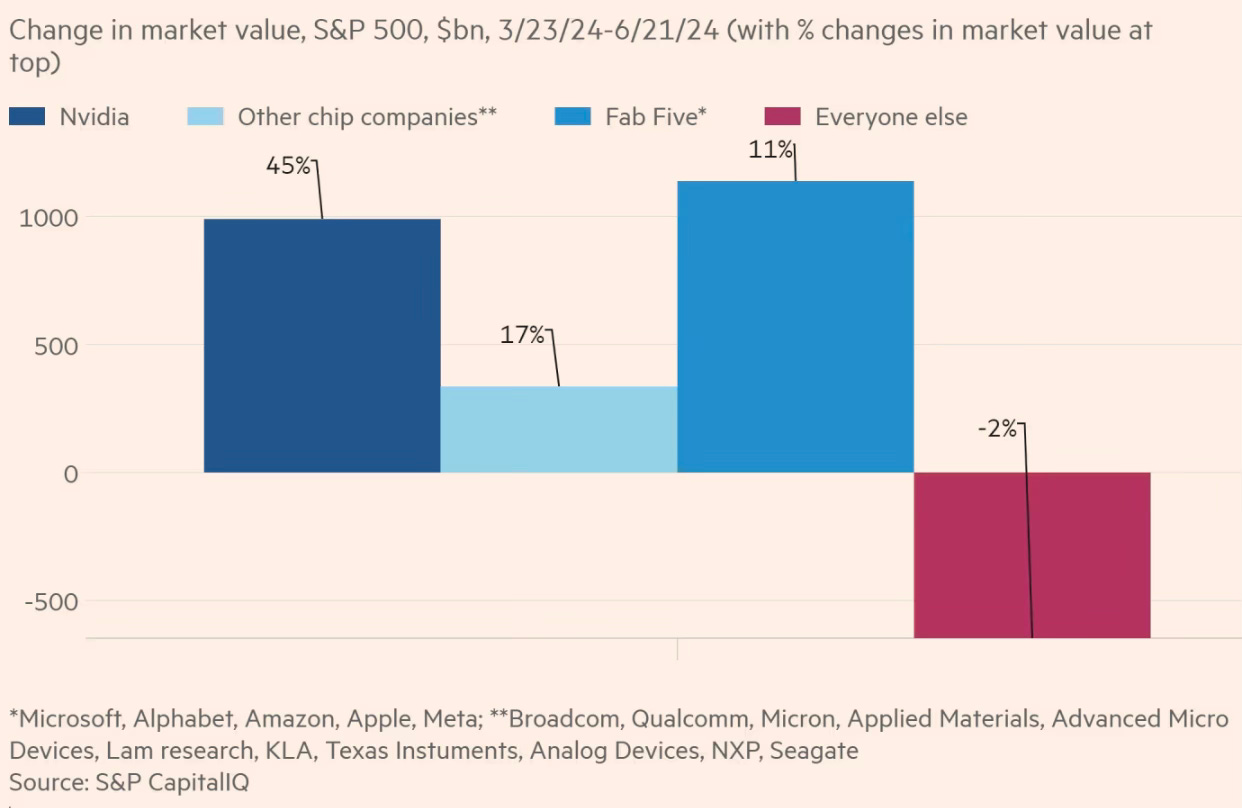

Another FT article points to the fact that all the gains in the S&P 500 since late March have come from AI or AI-adjacent stocks.

In the same period, the non-AI stocks are down 2%, with 9 out of 11 sectors are down.

As Robert Armstrong in Unhedged points out, it's hard for anyone to make informed choices given the conflicting trends on Nvidia.

Consensus estimates for revenue growth for next year and for 2026 do not, in fact, seem wildly demanding. Analysts are expecting a 23 per cent annual growth rate for Nvidia over that period. This would represent something of a moderation in rate; over the past five years Nvidia revenue has grown at 50 per cent a year. Similarly, the two-year revenue growth rates pencilled in for the Fab Five are at or below the growth rates of recent history. It is only a handful of the chip stocks — Micron, Texas Instruments, Analog, and Lam — where a major acceleration in revenue is expected. Is the recent rally in the AI group driven by upgrades of earnings estimates? Looking at 2025 estimates, not really. Since the end of March, earnings estimates for the group as a whole have crept up in the low single digits, percentage-wise. Apple, Amazon, and Micron are the only ones that have received meatier upgrades… In the past three months, the price/earnings ratios of Nvidia, Apple, Broadcom, and Qualcomm have all risen by over 20 per cent. Looking back to last October, when the rally began, the average (harmonic mean) P/E ratio in the AI group is up almost 50 per cent.

Unhedged also points to the internal tension within the AI rally

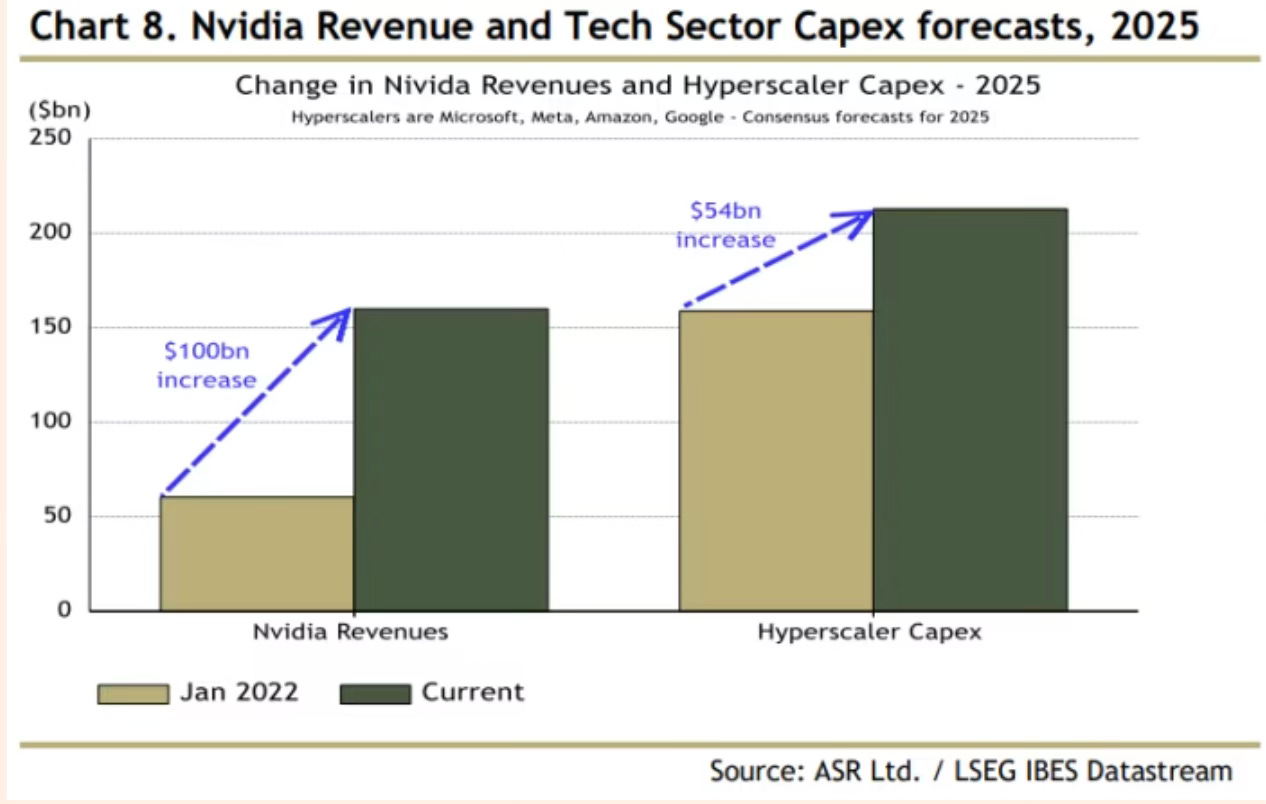

One internal tension within the AI rally is that the revenues of its leading company, Nvidia, are expenses for some of its biggest beneficiaries, the Fab Five. In the short term, Nvidia’s success is a drag on the cash flows of Big Tech companies, which are buying the bulk of Nvidia’s chips. Charles Cara of Absolute Strategy Research has recently made a provocative point about this. He notes that 40 per cent of Nvidia’s revenues come from Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Google, and that even the very large expected increase in capital expenditure at those companies is not very large relative to the expected increase in Nvidia’s revenues. The increase in the four companies’ capital spending between the last fiscal year and 2025, at $54bn, is more than 40 per cent of the $100bn expected increase in Nvidia’s revenues, but presumably only a fraction of Big Tech’s capital spending goes to Nvidia’s GPUs. So either the Big Tech will spend more, or Nvidia will make less.

Nvidia's stratospheric rise evokes comparisons with Cisco (instead of Microsoft and Apple).

The Nvidia economy looks very different to the one surrounding Apple. In many ways, the popularity of a single app — ChatGPT — is responsible for much of the investment that has driven Nvidia’s stock price upwards in the past few months. The chipmaker says it has 40,000 companies in its software ecosystem and 3,700 “GPU-accelerated applications”. Instead of selling hundreds of millions of affordable electronic devices to the masses every year, Nvidia has become the world’s most valuable company by selling a relatively small number of expensive AI chips for data centres, primarily to just a handful of companies. Large cloud computing providers such as Microsoft, Amazon and Google accounted for almost half of Nvidia’s data centre revenues, the company said last month. According to chip analyst group TechInsights, Nvidia sold 3.76mn of its graphics processing unit chips for data centres last year. That was still enough to give it a 72 per cent share of that specialist market, leaving rivals such as Intel and AMD far behind...

Demand for Nvidia’s products has been fuelled by tech companies that are seeking to overcome questions about AI’s capabilities by throwing chips at the problem. In pursuit of the next leap forward in machine intelligence, companies such as OpenAI, Microsoft, Meta and Elon Musk’s new start-up xAI are racing to construct data centres connecting as many as 100,000 AI chips together into supercomputers — three times as large as today’s biggest clusters. Each of these server farms costs $4bn in hardware alone, according to chip consultancy SemiAnalysis.

The biggest risk for Nvidia lies on factors beyond its control - whether the AI investments made by Big Tech will translate into proportionate benefits.

That scale of investment will only continue if Nvidia’s customers figure out how to make money from AI themselves. And at just the moment the company reached the top of the stock market, more people in Silicon Valley are starting to question whether AI can live up to the hype... Big Tech companies will collectively need to generate hundreds of billions of dollars more a year in new revenues to recoup their investment in AI infrastructure at its current accelerating pace. For the likes of Microsoft, Amazon Web Services and OpenAI, incremental sales from generative AI are generally projected to run in the single-digit billions this year... The period when tech executives could make grand promises about AI’s capabilities is “coming to an end”, says Euro Beinat, global head of AI and data science at Prosus Group, one of the world’s largest tech investors.

But Nvidia is not staying still. It’s constantly innovating both on its products and its business strategies.

Analysts say if it is to continue to thrive it must emulate the iPhone maker and build out a software platform that will bind its corporate customers to its hardware... It provides all the ingredients to build “an entire supercomputer”, Jenson Huang has said. That includes chips, networking equipment and its Cuda software, which lets AI applications “talk” to its chips and is seen by many as Nvidia’s secret weapon. In March, Huang unveiled Nvidia Inference Microservices, or NIM: a set of ready-made software tools for businesses to more easily apply AI to specific industries or domains. Huang said these tools could be understood as the “operating system” for running large language models like the ones that underpin ChatGPT... The problem for Nvidia is that many of its biggest customers also want to “own” that relationship with developers and build their own AI platform... Nvidia is cultivating potential future rivals to its Big Tech customers, in a bid to diversify its ecosystem. It has funnelled its chips to the likes of Lambda Labs and CoreWeave, cloud computing start-ups that are focused on AI services and rent out access to Nvidia GPUs, as well as directing its chips to local players such as France-based Scaleway, over the multinational giants. Those moves form part of a broader acceleration of Nvidia’s investment activities across the booming AI tech ecosystem. In the past two months alone it has participated in funding rounds for Scale AI, a data labelling company that raised $1bn, and Mistral, a Paris-based OpenAI rival that raised €600mn. PitchBook data shows Nvidia has struck 116 such deals over the past five years. As well as potential financial returns, taking stakes in start-ups gives Nvidia an early look at what the next generation of AI might look like, helping to inform its own product roadmap.

So what to make of this rally?

A paper by Philippe van der Beck, Jean-Philippe Bouchaud, and Dario Villamaina echoes the well-known herd effect among investors.

Many active funds hold concentrated portfolios. Flow-driven trading in these securities causes price pressure, which pushes up the funds' existing positions resulting in realized returns. We decompose fund returns into a price pressure (self-inflated) and a fundamental component and show that when allocating capital across funds, investors are unable to identify whether realized returns are self-inflated or fundamental. Because investors chase self-inflated fund returns at a high frequency, even short-lived impact meaningfully affects fund flows at longer time scales. The combination of price impact and return chasing causes an endogenous feedback loop and a reallocation of wealth to early fund investors, which unravels once the price pressure reverts. We find that flows chasing self-inflated returns predict bubbles in ETFs and their subsequent crashes, and lead to a daily wealth reallocation of 500 Million from ETFs alone. We provide a simple regulatory reporting measure -- fund illiquidity -- which captures a fund's potential for self-inflated returns.

Aswath Damodaran echoes the classic bubble talk

The AI story is expanding. I’m old enough to have seen multiple truly big changes, the ones that have changed not just markets, but the way we live. I started in 1981, so I saw the PC revolution. And then in the 1990s, the internet come in. And then social media come in. Each of these were kind of revolutionary, and in each of them we saw an over-reach — people taking every company in the space and pushing up prices. It’s the nature of the process. When people talk about bubbles, I say, what’s so wrong about a bubble? A bubble is the way humans have always dealt with disruptive change. What makes us change is the fact that we underestimate the difficulty of change and overestimate the likelihood of success. Whenever you have a big change, everything in that space will tend to get overpriced because people will push up the numbers, expecting outcomes that cannot be delivered. Eventually they come back to reality. It happened with PCs, it happened with dotcoms, it happened with social media.

When it’s all said and done, you have four or five big winners standing. Even if you believe this in the AI bubble, there’s no easy way to monetise that view. Short all these companies and you’ll be bankrupt before you’re right. So I look at these bubbles and I try to stay out of them. But I never thought that we should somehow stop the bubbles. Do you want to live in a world run by actuaries? We’d still be in caves, sitting in the dark. “This fire thing will get out of control!” We need people to over-reach. So with Nvidia at $850, it seems to me, the price has run ahead of the stock. I did a reverse engineering of how big the AI market would have to be and how big Nvidia’s share would have to be to justify the price. This was at $450. And I worked out that the AI chip market would have to be about $500bn, and Nvidia would have to have 80 per cent of the market, to essentially break even [In 2023, Nvidia’s revenue was $61bn].

Here's Robert Armstrong's conclusion in interpretation of the spectacular rally.

Perhaps it just reflects momentum and animal spirits. More charitably, it could reflect the expectation that the AI business will provide an increase in profits that lasts for many years into the future. That is to say, it is a bet about the competitive dynamics within the AI industry: that it will not be hypercompetitive, and the winners in the long term will be the same as the winners now — the Fab Five and today’s leaders in the semiconductor industry. To me, the second half of the bet, that the incumbents will keep on winning, seems like a reasonable one. Incumbency in tech is very powerful, to the extent that companies can use their strong market position in one technology to create a strong position in another (think of Microsoft moving from PC operating systems to cloud computing). The first half of the bet, that AI will not turn into a capital-intensive knife fight where no one makes high profits, I don’t know how to assess.

Clearly, nobody know with any great clarity for how long the technology companies will keep investing on AI-related hardware. As long as the technology companies feel the value (or peer-pressure) in adding to their capex, the very high margins and even higher entry barriers ensure that Nvidia will keep scorching ahead. The problem will arise when the tech companies stop their investments, either due to the realisation that AI’s commercial outcomes are falling short of expectations, and/or a disruption in AI that goes beyond the LLMs-based AI, and/or the next recession striking.

Update 1 (13.07.2024)

More on the topic. Here’s the optimistic case that the bubble is not about to burst anytime soon.

Nvidia said late last year that cloud companies — a market dominated by a handful of big players — accounted for more than half its sales of data centre chips. Any hint from the big tech companies during this earnings season that they are moderating their spending would deal a serious blow. Yet as tech companies prepare to announce their latest earnings, all the signs are that the boom is still in full swing. Many business customers have barely begun their first pilot projects using the technology and will be increasing their testing of the technology in the coming months, even if it’s unclear what ultimate uses they will find for it. Pouring money into large language models and the infrastructure to support them has also become a strategic necessity for the big tech companies themselves. If machines that can “understand” language and images represent an entirely new computing platform, as many in the tech world expect, then all the big players will need a stronger foothold in the technology…

It’s also worth noting that these companies have more than enough financial firepower to maintain and even escalate the battle. The combined operating cash flow of Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta jumped 99 per cent in the past five years, reaching $456bn in 2023. That was more than enough to accommodate capital spending that ballooned by 96 per cent to $151bn. Meanwhile, the next big product cycle for chipmaker Nvidia, based on its new Blackwell chip architecture, isn’t even due to begin until the second half of this year. The lower costs this promises for training and running large AI models have guaranteed a stampede from customers, even as demand for its earlier generation of chips remains strong.

No comments:

Post a Comment