There’s a puzzle about the Indian economy. A newspaper report informs that private capex plans announced in the Q1 of 2024-25 have slumped to a 20-year low. Another report points to a deceleration in sales and profit growth of private companies in the first quarter of 2024-25.

Why is private investment stagnant despite several steps by the government and vibrant animal spirits about the country’s economic prospects?

Despite strong and pretty long pump-priming by the government with a near doubling of capital expenditures, transformational upgradation of infrastructure, significant improvements to the ease of doing business, credit markets being flush with funds and willing to lend, and favourable global tailwinds, private investment in India remains stuck. It’s all the more surprising given that Indian corporates are very well-placed to invest - they deleveraged during the last decade, used the pandemic to shed labour and automate, benefited from the steep cut in corporate tax rates, have enjoyed the generous incentives across sectors from the Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme, and tariff walls have gone up to provide domestic industry with more than sufficient protection. Finally, animal spirits about the economy are at their most animated, domestic investors are flooding into a booming stock market, and global interest in the Indian economy has never been this good.

The Indian government has done most things that would be expected of any government to support economic growth.

The market conditions have improved dramatically in recent years. The corporates themselves are in the pink of health. Consider these statistics about corporate profits

Data of more than 5,000 listed companies from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy suggests that from 2018-19 to 2022-23, the net sales of these companies went up 52%, corporate taxes paid went up only 36% and their net profit rose sharply by 187%. In comparison, between 2014-15 and 2018-19, net sales had gone up 30%, corporate taxes by a higher 38% and net profit in 2018-19 was around 90% of the profit in 2014-15. Clearly, among other things, lower taxes have helped spruce up profits of listed companies, pushing up stock prices.

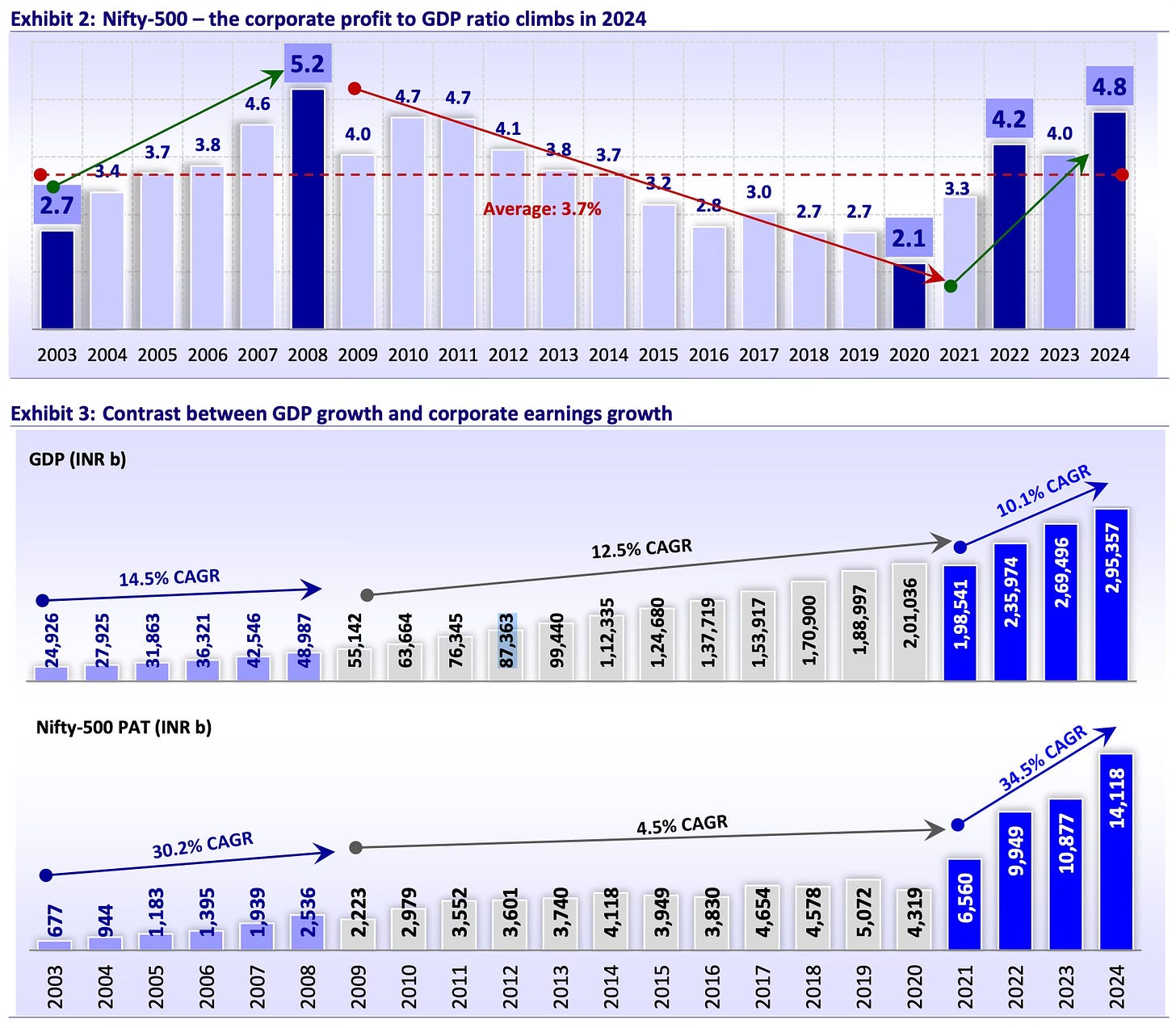

A recent report by brokerage firm Motilal Oswal analysed corporate earnings as a share of GDP for the period from 2003-24. Its findings are captured in this graphic. the ratio is at a 15-year high, and it has grown at more than thrice the nominal GDP growth since the pandemic.

Interestingly, the increase from 2.1% to 4.8% in the 2020-24 has been driven mainly by oil and gas, automobiles, metals, and utilities. In contrast, sectors like consumer goods, consumer durables, and retail have been stagnant.

See also this and this. This Indian Express article points to the sharp dissonance between anaemic topline growth co-existing with booming bottom-line (PAT) growth rates.

According to a November 2023 CMIE estimate, over the past three and half years, listed companies have generated Rs 17.7 trillion as additional net profits while their net fixed assets had grown by only Rs 4 trillion and their investments into financial investments increased by Rs 6.2 trillion. In other words: India Inc. is not particularly constrained to expand its capacity. It, however, chooses to refrain.

Though Indian corporate leaders themselves have been gushing and swooning about the prospects of the Indian economy, they have been unwilling to put their money where their mouth is and restart the private investment cycle. Private investment remains far below what should have been the case. It’s the dog that has not barked. What explains this?

In a recent oped, Arvind Subramanian and co-authors point to a possible explanation, the failure of the government to address the problem of investment risk. Specifically, they point to the government’s preference for a “national champions” strategy that tilts the playing field against competitors; aggressive tax demands and coercive enforcement actions; and supply chain risk arising from abrupt tariff changes, especially on raw materials and inputs sourced from other countries.

While all of them are risks and they should be addressed, I’m not sure any of these are binding constraints to the economy. The risk of the national champions strategy, if at all, is confined to the infrastructure sector and does not explain the broad-based manufacturing and economy-wide investment stagnation. Both Japan and South Korea followed this approach and it did not do them any bad. In fact, a new paper finds that in South Korea “exceptional performance of the top 3 firms within each sector relative to the average firms contributed 15% to the 2011 real GDP and 4% to the net present value of welfare over the period 1972-2011”. The aggressive tax demands have been a constant feature of the Indian economy, even in times when FDI inflows were booming. Further, the much higher regulatory capricity risk in China has not deterred investors. The supply chain risk, while important, is cognitively amplified by the few high-profile cases and impacts only a small part of the economy, though the high tariffs on inputs and resultant effect on competitiveness is a problem. None of these can explain the broad-based economy-wide stagnation of private investment.

Let’s for a moment keep aside foreign investors and activities that are critically dependent on imported inputs. India is the third (or fifth) largest economy in the world and therefore has a massive domestic market. It has a very diversified and rich industrial base. Therefore, even with all these risks and constraints, given the country’s recent rapid growth rates and animal spirits surrounding the economy, the private sector should be opening their investment taps. A massive and rapidly growing economy like India’s will have several national economy-sized market segments which are large enough to justify large investments. At the least, private investment growth should be commensurate with the economic growth rates.

So what’s keeping down private investment?

The Indian Express article mentioned earlier raises a set of questions that might give pointers.

Why are listed non-financial companies not able to register higher sales in a fast-growing economy? Moreover, how long can companies continue to make profits without raising their sales? If companies are not able to substantially increase sales, would they invest in fresh capacities, regardless of their profits?

A long-running theme of this blog, and best captured in my first co-authored book, Can India Grow, is that, unlike China, India does not possess the financial, physical, personnel, and institutional capital to sustain high growth rates for long enough periods. The consumers cannot absorb the scale of supply, the labour market cannot supply the scale of skilled workforce required, and the private sector cannot provide goods and services at the scale required to support the high growth rates. In this chain of demand and supply, the consumer demand is critical.

I have blogged on several occasions drawing attention to the narrow economic base of the formal productive economy and the need to broaden it. Without significant broadening of this base, India will struggle to generate the kind of demand required to justify higher levels of corporate investment.

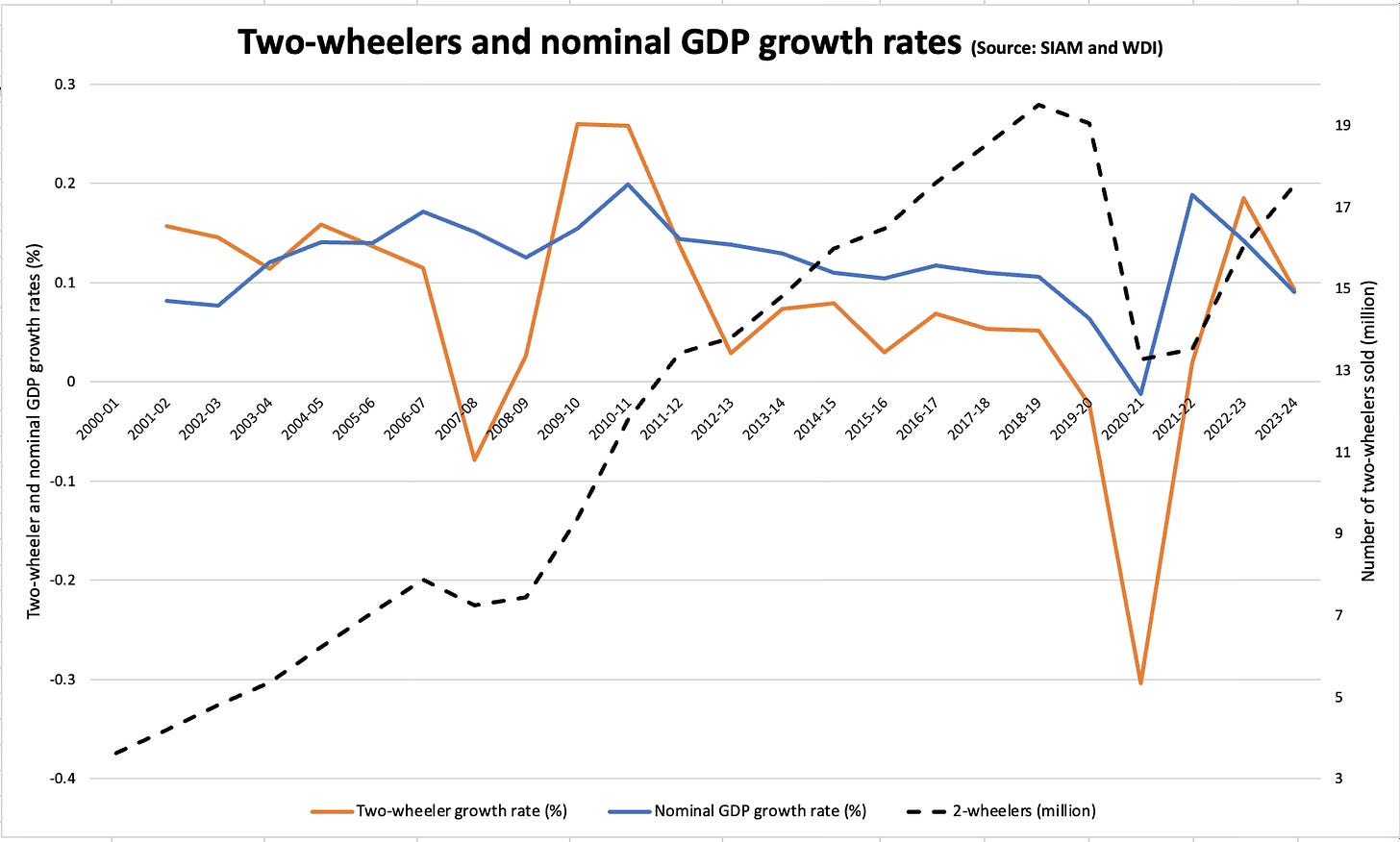

There are several signatures of this narrow base from across market segments and it’s also reflected in the low sales growth of consumer durable goods, poor affordable housing loan off-take, slow deposit growth in banks, and tepid topline growth of private companies in general. A reasonable proxy for the narrow base of the economy can be the trends in the sales of two-wheelers.

Indeed, two-wheeler sales have nearly doubled over the last decade before the pandemic struck. However, the sales growth has remained far below the nominal GDP growth rate. In an economy growing at 6-8% real rate, which has experienced steep drop in those below the poverty line, which has very low two-wheeler penetration, where two-wheelers are seen as an important aspirational acquisition and a marker of economic mobility, it’s surprising that the two-wheeler sales have grown at about only half the rate of nominal GDP growth during most of last decade. Yes, the rates are up in the last two years and it’ll be interesting to see whether it’s a secular trend or a base-effect after the pandemic.

Even at the top end of the market segment, the Indian market is tiny, compared to say the Chinese equivalent. As an illustration, luxury brand LVMH had 950 stores in China employing 24,000 people as of 2019 and added another 58 stores just in 2023. In stark contrast, all of India today has just five stores!

For sure, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) has been on a downward trajectory since the 2003-08 boom. In fact, it never recovered fully from the depths of the global financial crisis and subsequent corporate indebtedness problems. Private investment dropped from around 27% in 2007-08 to 19.6% in 2020-21.

Strong and large enough demand growth is also important to sustain innovation. As I blogged here, companies in frontier industries require good margins and associated cash surpluses to be able to innovate and experiment to expand the boundaries of technology and markets. India’s deeply price-sensitive consumers and very small base of affluent consumers mean that companies have to work on small margins and a low demand base even at the top market segments. This can be a binding constraint to innovation, market development, and investment in sectors like electric vehicles. The high levels of indirect taxes add to the challenges faced by businesses.

I’m therefore inclined to believe that the primary reason for the anaemic investment growth is the consumer. Specifically, the signatures of consumption growth across segments may not merit a supply response that’s more than the current one. In other words, the slow pace of investment growth is only a reflection of the demand weaknesses.

But this cannot explain the corporate sector’s failure to increase investment rates. It’s clear that the corporates used the pandemic to cut manpower costs, increase automation, deleverage, and fortify their financial position, and are reaping its benefits in the form of high margins and record profits. But this cannot go on without commensurate topline growth, which is of course dependent on consumer demand.

Be that as it may, the record surpluses are a great opportunity for corporates to invest in innovation and R&D, the foundation for future growth and increasing global competitiveness, which are also the traditional weakness of India’s private companies. Given the very promising long-term economic prospects of the country and the 6-8% GDP growth rates in recent years, it’s short-sighted on the part of corporations to pull back on investments on grounds of demand weakness.

There’s an endogeneity between investment and demand. After all, aggregate demand and broad-based growth come from greater productivity, higher wages, more investment, and newer jobs. The government has been doing its bit. It’s well past time for the private sector in India to step up.

// therefore inclined to believe that the primary reason for the anaemic investment growth is the consumer. Specifically, the signatures of consumption growth across segments may not merit a supply response that’s more than the current one. In other words, the slow pace of investment growth is only a reflection of the demand weaknesses.

ReplyDeleteBut this cannot explain the corporate sector’s failure to increase investment rates.//

Great post but aren't these two points contradictory?