This is the latest in the series of annual posts on the state of global infrastructure finance and its lessons for India's infrastructure financing plans. The earlier versions are here, here, here, here, and here.

The unambiguous takeaway is that contrary to the hype among investment bankers, consultants and boosters in the media, India's infrastructure financing has to come from domestic capital sources. For policy makers captured by this hype, sooner the reality check, better for the country's massive infrastructure financing needs. This is more evidence on a problem on which I have written a very long paper here.

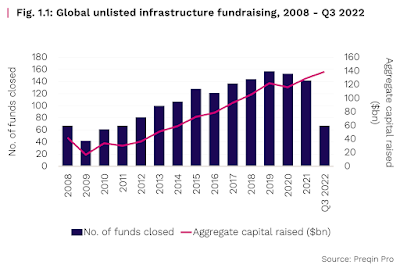

1. This is the summary of global unlisted infrastructure funding raised over the last 15 years.

2. This is the summary of the destination of these funds - in 2022, just $8 bn was bound for Asia, and the region's CAGR for 2017-22 was -10.8%. It has been in the $4-9 bn range for the last five years. For all practical purposes, such funds are largely US and Europe bound.

3. And within the infrastructure space too, most of the funding is going into renewable energy, telecommunications and internet, and highways. Traditional energy (which includes water and utilities) and social infrastructure are small and declining.

4. This is the summary of trends on global assets under management (AUM) by the PE industry. As can be seen, infrastructure makes up a very small share.

5. From the same McKinsey report, on AUM in the H1 of 2022.This is the break-up of the dry powder available across sectors, of which infrastructure is very small.

6. And this is the break-up of capital raising, which too shows a very small share for infrastructure.

7. Unlisted or private infrastructure funding has been on the downward trend.

8. Infrastructure was a small share of the total VC/PE investments, domestic and foreign, in the country.

9. And even within infrastructure, as the table below shows, the funding typically goes into renewables and roads.

10. Finally, most of the investments are in brownfield assets and involve large size deals.

On a separate note, the Indian VC investments are overwhelmingly on the (mostly copycat) consumer tech, fintech and SaaS side, and has very little going into manufacturing.

The clear conclusion from this are four-fold

1. Given the numbers above, India's infrastructure investment needs will have to be met almost completely from domestic sources. Even in theory, since infrastructure revenues are in domestic currency and since the sectoral returns are smaller compared to other assets, foreign investors cannot be anything other than marginal contributors.

2. To the extent that local finance, equity and debt, will be required to finance most of infrastructure, the binding constraint to expanding infrastructure investments will be their availability. On both the equity and debt sides, infrastructure demands long-term (patient) capital with moderate returns appetite. Infrastructure will be part of a portfolio of investments, balancing out risks while offering lower returns.

3. The major share of private equity in infrastructure will go into brownfield assets to replace private or public equity, and therefore will be in the form of large ticket size deals. Given the uncertainties with construction risks, it'll be very difficult to attract investors into greenfield investments and smaller brownfield assets.

4. Within the infrastructure fold, the major share of investments go into two areas - renewable energy (26%) and telecommunications (30%). These are two sectors where public investments are in any case already a very small share. And most of the remaining target brownfield highways, where too private investments are the norm. In contrast, the dry powder available to invest in urban infrastructure, downstream electricity, public transportation, affordable housing, social infrastructure etc is vanishingly small.

So, as mentioned earlier, the major part of India's public goods infrastructure funding has to come from the governments, banks, and public markets. In this paper, I had categorised infrastructure into four groups, and shown that most of the public goods investments (urban infrastructure and utilities, electricity distribution, public transport, social infrastructure, irrigation, and affordable housing) will have to come from public sources.

More specifically, a financing strategy for infrastructure for countries like India could look something like this

1. Infrastructure financing in large countries like India will have to be almost completely driven by local long-term finance. Foreign capital will be marginal and catalytic in certain areas.

2. Certain types of private infrastructure like electricity generation and telecommunications, and public infrastructure like electricity transmission and national highways, can be mostly privately financed either as greenfield or brownfield. But there are limits to how much private capital is available to invest.

3. Greenfield projects face the problem of very high construction risks (from financial closure, permissions and clearances, right-of-way or site acquisition etc). Therefore the main source of greenfield public goods infrastructure financing will have to be from the government, which alone can bear these construction risks. This government financing can be directly from the budget, from local governments, government corporations, and government-owned special purpose vehicles. Each of them will have to figure out ways to leverage debt through loans and bonds.

4. After construction risk is off-loaded, brownfield assets which are revenue generating can be privatised or monetised, thereby freeing up public finance to take on newer investments. A framework that facilitates monetisation is essential to achieve this objective.

5. Those assets which cannot monetised can be given out in long-term concessions for operation and maintenance. Like with monetisation, a robust framework on concession management and renegotiations is critical to success of concessions too.

Both monetisation and concessions allow for recycling of government equity.

6. Public finance will have to be leveraged mainly with bank loans, structured through various means like syndication, takeout financing etc so as to address the asset-liability mismatches.

7. The critical challenge will be to expand the envelope of domestic equity and debt with the interest to invest in infrastructure. The sector is less risky and therefore offers lower and stable returns. This is not the ideal thing for equity investors who are generally looking at higher returns, though within a portfolio infrastructure can be a small asset category.

8. There are perhaps two approaches to expand the envelope of scarce risk capital equity. One approach would be to facilitate the entry of more infrastructure contractors and O&M operators. This would entail proactive approach by the government to lower entry barriers in public contracting so as to expand the pool of infrastructure contractors and therefore the likely sources of risk capital. These contractors will combine both private and public market equity.

9. Another approach to address the problem of scarce equity is to encourage the development of infrastructure funds. These funds aggregate risk capital from investors (the limited partners) and invest them in a portfolio of infrastructure projects or in the infrastructure contractors themselves (as either private or public equity).

Typically, the contractors prefer to assume higher risks so as to earn higher returns, which attracts them to construction contracts. In contrast, infrastructure funds prefer to come in after commissioning of the project and are satisfied with the lower but stable returns.

These two approaches together allow for recycling of scarce private equity capital.

10. On the debt side, bond markets will have to be deepened to the extent possible so that it can supplement bank loans. But, as I have written on numerous occasions citing evidence from across the world (except the US), there are strong limits to such deepening and they'll remain distant secondary debt sources compared with bank loans. See this and this.

Creating the enablers for pension funds and insurance funds to invest in these bonds is essential to such deepening. On the supply side, enablers like credit guarantees and other credit enhancement instruments should be used to encourage debt issuers, especially the most credit worthy ones, to shift from banks towards capital markets.

11. The likes of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) and outright private provisioning will invariably be marginal sources of financing of public goods infrastructure.

12. Finally, the political economy risks of long-term contracts will have to be mitigated if we are to make any progress in these directions. This would require strengthening of regulatory frameworks (and their enforcement), inviolability of contractual obligations on all sides (so, for example, tariff increases will have to be seen through), and insulation of such contracts from political transitions.

No comments:

Post a Comment