John Burn-Murdoch has an excellent op-ed that compares the views of politicians and voters in Western countries on economic and sociocultural issues. He cites the work of political economist Laurenz Guenther, who draws attention to a remarkable convergence on the former and divergence on the latter.

Guenther’s analysis shows that voters and mainstream politicians have long been broadly aligned on economic issues like tax and spend or public ownership. But on sociocultural issues such as immigration and criminal justice there is a yawning gulf. Western publics have long desired greater emphasis on order, control and cultural integration. Their politicians have tilted in the opposite direction, favouring more inclusive and permissive approaches. The result is the opening up of a wide “representation gap” — a space on the political map with large numbers of voters but few mainstream politicians or parties — into which the populist right is now rapidly expanding as cultural issues rise in salience.

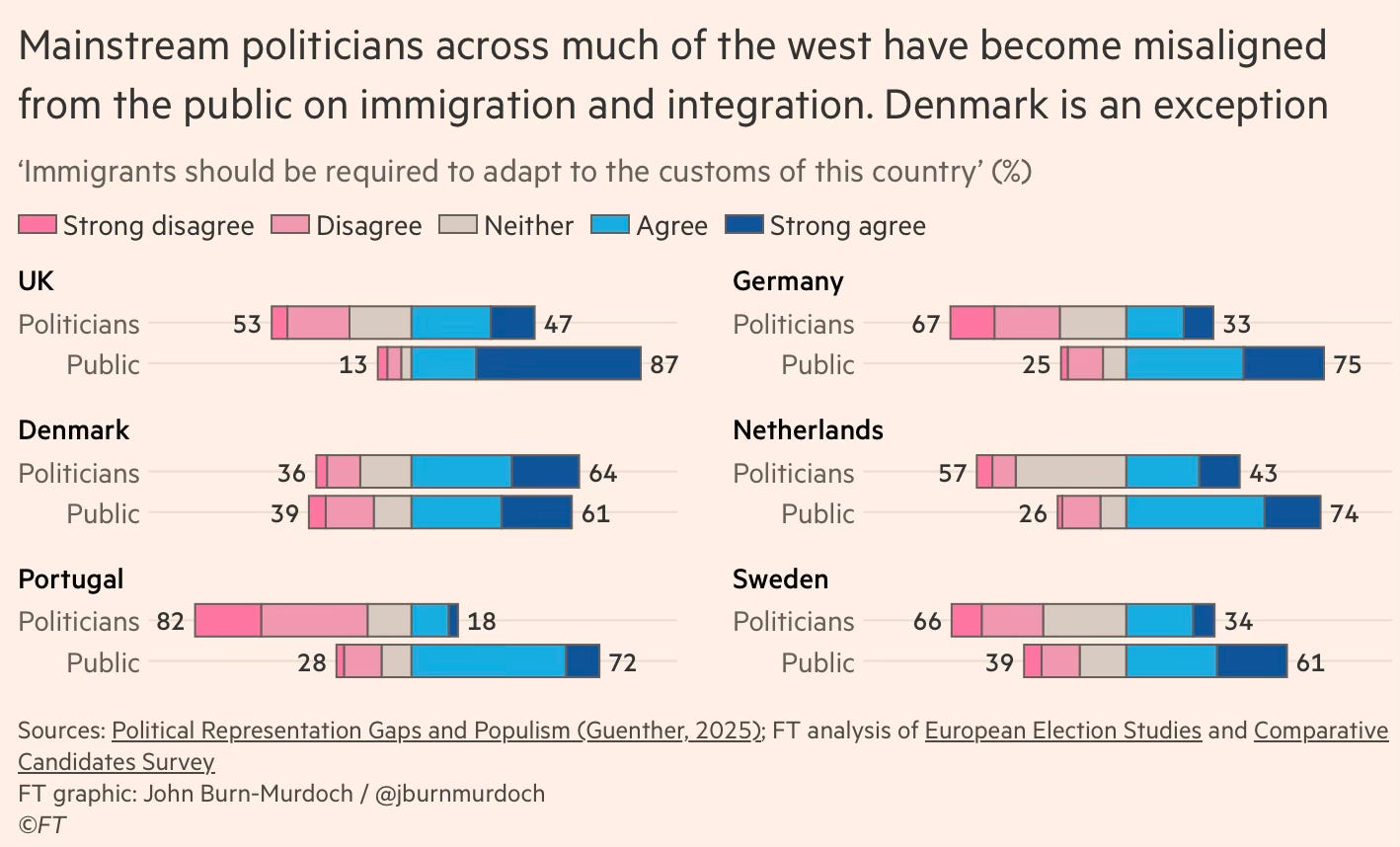

Aside from Denmark, he finds a sharp divergence between the views of politicians and voters on sociocultural issues.

Burn-Murdoch also writes that

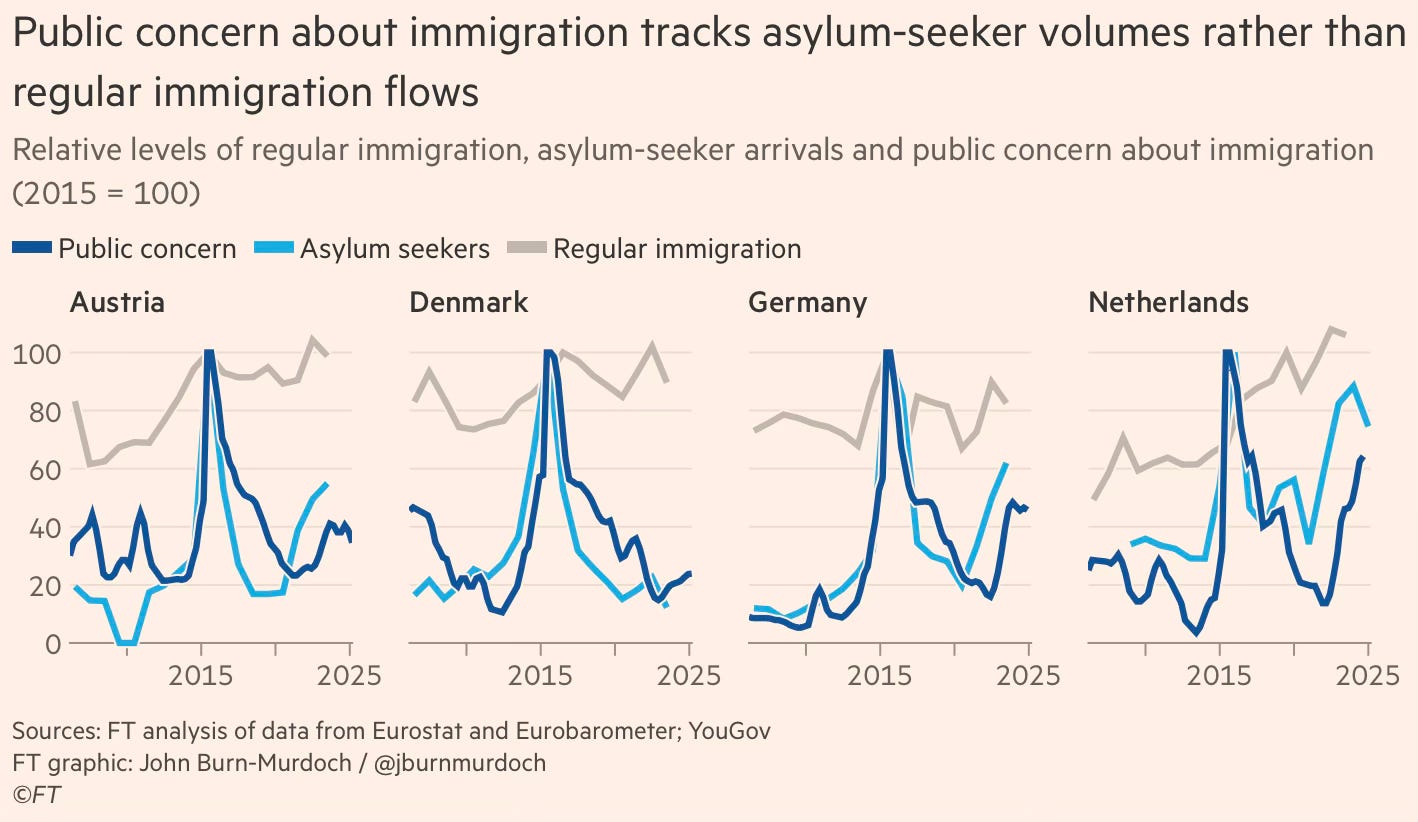

My analysis of decades of data on public perceptions and immigration levels shows that concern consistently tracks irregular migration and failed integration, not people coming to work and study. But Guenther’s research corroborates the consistent finding that the public does not want large flows of arrivals without visas, or a growing share of the population unable to speak the language (both of which have happened). A similar pattern is clear with crime, where rates of arrest and prosecution have fallen in several countries and lower-level disorder is on the rise. Sustained failure to curb these trends under governments of both the centre left and centre right has signalled to the public that the political class either doesn’t see this as a problem or is incapable of addressing it.

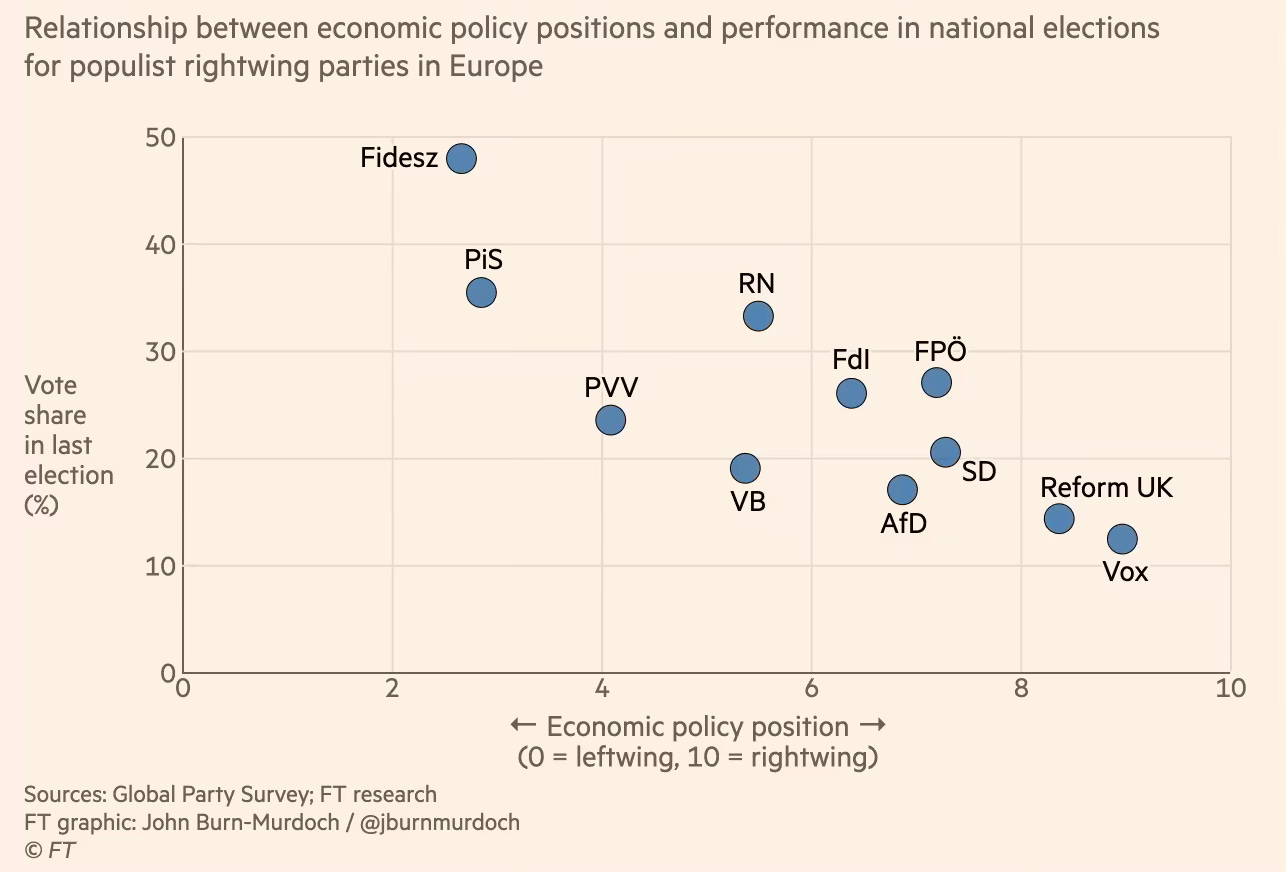

In another article, Burn-Murdoch has shown how “populist parties on the right combine rightwing positions on social issues with left-wing positions on economics”.

In a third article, he points to declining fertility levels among progressives as a possible explanation for the world becoming more socio-culturally conservative.

I find that the assumption that birth rates are falling across society in general is not really true. From the US to Europe and beyond, people who identify as conservative are having almost as many children as they were decades ago. The decline is overwhelmingly among those on the progressive left, in effect nudging each successive generation’s politics further to the right than they would otherwise have been… A growing left-right birth rate gap will slow that liberalising conveyor belt, and could result in societies and politicians that are less liberal and less concerned with the environment than would otherwise be the case.

The dissonance between the political parties and their voters on socio-cultural issues is surprising, given the importance politicians tend to attach to public opinion surveys. It begs the question as to why parties are unable to recalibrate their positions to reflect the views of their electorate. Also, what explains the dissonance being confined to socio-cultural issues and not to economic issues?

An important reason for the failure to incorporate public perceptions, as I have blogged here and here, is that the leadership of mainstream political parties have become captives of certain interests. This is especially true of the centre-left or social democratic parties, whose leadership largely consists of the beneficiaries of the capitalist economic system. Their social and cultural proclivities are towards the liberal positions on immigration, diversity, minority rights, etc. Sample this description of the Democratic Party leadership in the US.

Since 1980, among all Democratic candidates for president and vice-president of the US, Tim Walz, Kamala Harris’s running mate, was the first not to have a law degree. During the same period, none of the four Republican presidents had a legal background: the first, Ronald Reagan, was an actor and the other three were businessmen. In the US, lawyers are rivalled only by politicians as the most hated professional group. Is it any wonder, then, that the lawyers’ party was overwhelmed? That a platform entirely conceived by lawyers, centred on the defence of democratic procedures and respect for minority rights, whose main argument consisted in the lawsuits against the Republican candidate, was swept away by the recriminations of Trump supporters: inflation, illegal immigration, class contempt?

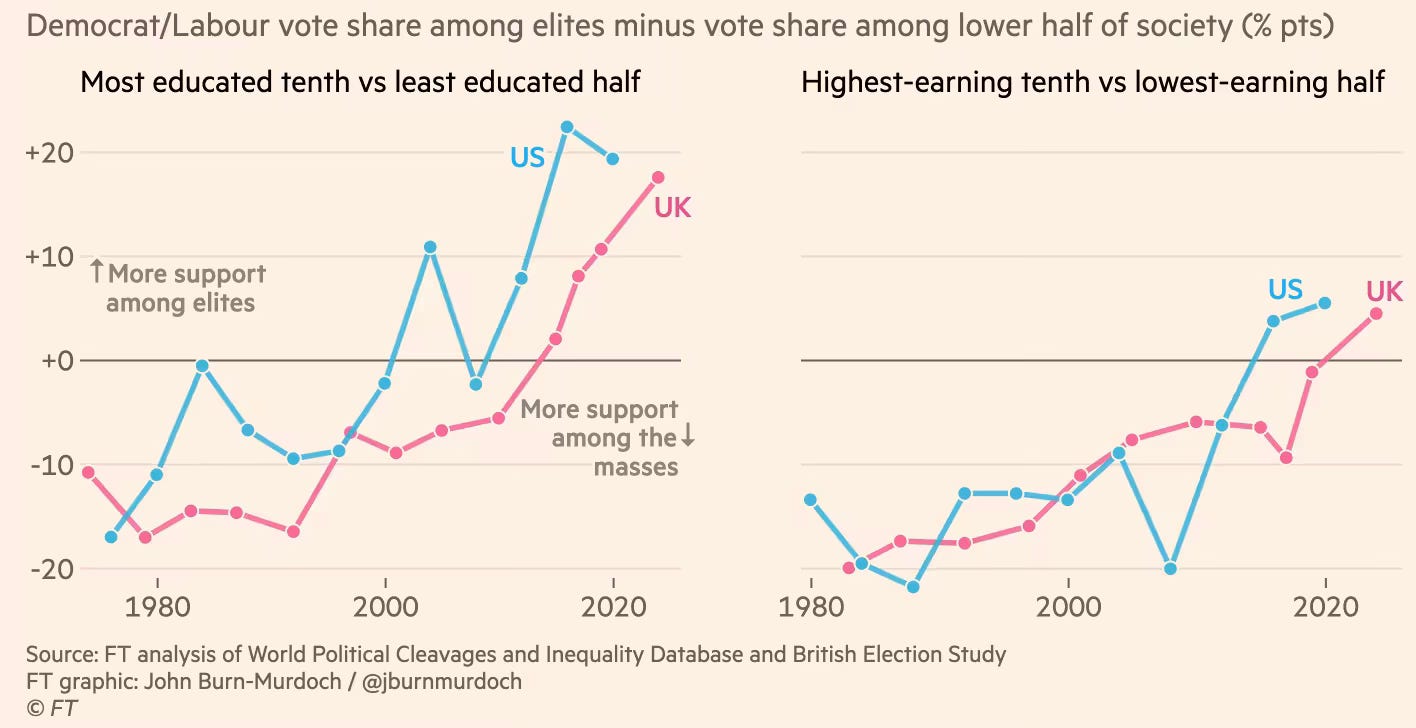

It’s not unsurprising then that in the aggregate, left-wing parties tend to fare better with elites than with the masses on both sides of the Atlantic.

Burn-Murdoch points to the idea that class has been replaced by education as the new defining cleavage in politics.

In their book Polarized by Degrees, political scientists Matt Grossman and David Hopkins set out how the realignment of the political divide from class to education has formed strong new alliances that are likely to survive changes in political personnel. While arts and entertainment elites have long leaned leftward, academia has veered further to the left of the general population over recent decades. Conservatives have become a rare breed in journalism, and corporate bosses are increasingly aligned with the left.

While the occupational base of Republican Presidents and candidates may have been more diverse, their economic class base is narrower and has several common features with their Democratic Party counterparts. The traditional left-wing mass electoral base of factory and service industry workers, and the right-wing mass base of primary sector and hinterland residents, are characterised by their lower levels of education, especially compared to the political leadership of both Parties in the US. This explains the comparable levels of dissonance between them and their respective electoral bases on socio-cultural issues. The class dominance has come in the way of their remaining connected with the social views of their electorate.

However, as Rana Faroohar writes, there’s an important, unmistakable emerging political reality arising from the deepening of the class-based dissonance. It’s called populism, of either variants.

Whatever the outcome, it’s clear that future elections are going to be won or lost on who can convince working people that they will fight for them. For example, the issue of healthcare affordability — surveys show premiums will probably rise by 10 per cent or more next year — is driving the launch of “TrumpRx”, a federal website through which Americans will be able to purchase discounted drugs (ironically taking a page from Obamacare). The affordability crisis is also behind the rent freezes and municipally owned groceries suggested by (Zohran) Mamdani.

The alignment on economic issues is more intriguing, especially given the clearly widening inequality and rising relative deprivation in the US. Besides, there are clear faultlines along education levels between political leadership in both Parties and their respective electorates.

I’m inclined to argue that while the dissonance between political leadership and electorate will be less likely (at least for now) on broad principles like support for the capitalist system with a social welfare net (as captured in the survey mentioned above), it’s likely to be more pronounced on issues like business concentration and anti-trust actions, or tax cuts and welfare squeezing, or deregulation and quality of job creation.

No comments:

Post a Comment