1. Revival of manufacturing in the US faces a collective action problem! It's good as long as I'm not working in manufacturing.

Interestingly, real value-added by US manufacturing has risen sharply even as employment has fallen.This is also reflected in the shift up the value chain in the sectors involved.Since 1990 America has lost over 5mn manufacturing jobs. In that time, it has gained 11.8mn roles in professional and business services, and 3.3mn in transportation and logistical activities, linked to multinational supply chains.

2. One of the most important requirements for a deal between two parties is the space available to negotiate and their credibility as negotiating partners (preferably in terms of track record). If you present the other side with an egregiously unacceptable deal, then it virtually eliminates the likelihood of a deal even before the negotiations have started.

The Trump administration appears to have erred in two very high-profile negotiations. The magnitude of the tariffs imposed on China and the subsequent public posturing may have made it impossible for the Chinese to not retaliate. On the same lines, the contents and the tone of the letter to Harvard and the track record of Columbia's submission failing to win reprieve on the release of funds meant that Harvard could not but reject the proposal. This tweet describes it nicely.

Bullies can't make deals.

3, Tyler Cowen makes a good point

The inconvenient truth, for China, is that its scale relies upon American power and influence. The Chinese export machine, for instance, requires a relatively free world trading order. The recipe to date has been “mercantilism for us, free trade for everybody else.” Yet Trump threatens to smash that framework. If the world breaks down into bitterly selfish protectionist trading blocs, China will be one of the biggest losers. After all, where will the Chinese sell the rising output from their factories?

4. Financial markets and Liberation Day

American economic success in the era after the second world war depended on innovation, which in turn relied on strong institutions that encouraged people to invest in new technologies, trusting that their inventiveness would be rewarded. This meant a court system that functioned, so that the fruits of their investments could not be taken away from them by expropriation, corruption or chicanery; a financial system that would enable them to scale up their new technologies; and a competitive environment to ensure that incumbents or rivals couldn’t block their superior offerings. These kinds of institutions matter under all circumstances, but they are especially critical for economies that rely heavily on innovation... A basic pillar of the American century was the country’s ability to shape the world order in a way that was advantageous for its own economy, including for its financial and tech industries... Democracy’s bargain everywhere, and especially in the US, was to provide shared prosperity (economic growth out of which most people benefited), high-quality public services (such as roads, education, healthcare) and voice (so that people could feel they were participating in their own government). From around 1980 onwards, all three parts of this bargain started to fall away.

Unsurprisingly, given his research focus on institutions, he traces America's decline to the erosion of its institutions, which gathered pace during the Trump administration. He foresees increasing business concentration and dominance by the Big Tech firms which come to a head in early 2030s resulting in a massive crash and economic collapse.

But the real extent of the damage became clear only with the tech meltdown of 2030... After Trump lifted all roadblocks ahead of AI acceleration and cryptocurrency speculation, there was initially a boom in the tech sector. But within a few years the industry had become even more consolidated than before, and both insiders and outsiders came to realise that only companies favoured by the administration could survive. Gargantuan incumbents began crushing rivals, first by using their financial might, then by luring competitors’ workers and innovators (who curiously stopped producing valuable patents once they had joined these mega-firms) and ultimately by stealing their intellectual property. By this point, US courts had lost most of their objectivity, and because the mega-firms were the administration’s friends and allies, they benefited from favourable rulings even when they were blatantly stealing from smaller competitors and engaging in predatory pricing and vertical foreclosure to drive them out of the market. By late 2029, many commentators were questioning what was going on in the tech industry, which had invested heavily in AI but had little to show for this in terms of innovation or productivity growth.

6. In a brilliant essay, Sarah Churchwell compares today's America to that of the Great Gatsby's.

During the novel’s composition, Fitzgerald immersed himself in reading about Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West. Spengler wouldn’t be translated into English until after Gatsby’s publication; Fitzgerald was gleaning his ideas for it from other writers. But he assimilated Spengler’s vision of a world where power-hungry leaders rose from cultures grown cynical and spent — ideas the Nazis later appropriated. Fitzgerald recalled responding to Spengler’s sense of civilisational senescence — what he described as “gang rule . . . the world as spoil”. Fitzgerald absorbed from these sources a pervasive sense of cultural decline, where hope feels both essential and doomed... Gatsby reaches beyond the moral failures of its characters to expose carelessness as a political force. This includes not only the oligarchy’s immunity from consequence, but also the way extraction was equated with success. The unheeding brutality of so-called world-builders has returned most recently in the dark fantasies of Trumpism, and in Silicon Valley’s fatuous motto, “move fast and break things”...Exploiting anxieties about cultural collapse and demographic shifts, Trumpism frames progress as decline, insisting America must forcibly reshape itself to resemble a mythologised past. If there is a philosophical undercurrent to this panic, it is the same ambient declinism revived by today’s “Dark Enlightenment” ideologues — neo-reactionaries who dress authoritarian nostalgia and rigid hierarchy in the guise of pragmatism. These movements posture as intellectually serious but offer only recycled grievance, cherry-picked from a deeply unserious reading of history. The Dark Enlightenment advocates for replacing democratic institutions with authoritarian governance led by a powerful executive, often likened to corporate management... Some Dark Enlightenment thinkers tout “accelerationism”, which seeks to hasten the breakdown of current systems to pave the way for authoritarian governance... People such as Thiel, Elon Musk and Donald Trump seem to find democracy vexatious because it is a theory of power-sharing. Tech moguls who glorify efficiency and advocate “exit” from democratic accountability imagine themselves natural rulers, reasserting hierarchies that protect their privilege. Ironically, of course, it is the very democratic and economic infrastructures they scorn as obsolete that enabled their rise.

7. Good primer on wealth tax, with focus on the UK.

8. Rote learning and concepts remain the focus of India's school education system.

9. Globalised supply chain as illustrated by car manufacturing in the US (HT: Adam Tooze).The big losers are likely to be the biggest beneficiaries of globalisation — American multinationals. As barriers to trade and capital fell in recent decades, US corporations increased profits much faster abroad than at home. Profit margins for S&P 500 companies had held steady since the 1960s. Then margins nearly doubled to around 13 per cent after 2000, coinciding with China’s entry into the WTO. Many US giants generated “supernormal” profits, far higher than their developed world rivals, by cashing in on the appeal of American brands and outsourcing production to nations with the cheapest costs. Today, US multinationals generate more than 40 per cent of their revenue abroad. The biggest gainers were manufacturers, which on average pay their workers overseas 60 per cent less than staff at home.Now, American businesses will think twice before setting up new factories abroad and decisions will not be driven by the straightforward logic of maximising profitability. The large multinationals in particular will see profit margins under constant pressure. Amid anger over tariffs, “Made in America” is attracting more controversy than customers. Two in three Germans say they are avoiding US products. Social media campaigners are organising boycotts in Sweden and France. No nation is more irate than Canada, where consumers are switching from US to Japanese whisky, cancelling US streaming services and calling off trips to their southern neighbour.

12. The rise and rise of gold

Vietnam and Indonesia have been big beneficiaries of the migration of labour-intensive manufacturing, gaining more than 10 million jobs since 2011. Their exports have grown at 12.3% and 8.2% respectively from 2019-23.

Analysis of 12 labour-intensive manufacturing industries between 2011 and 2019 by academics at Changzhou University, Yancheng Teachers University and Henan University found that average employment shrank by roughly 14 per cent, or nearly 4mn roles, between 2011 and 2019. Roles in the textile industry shrank 40 per cent over the period. An FT analysis of the same 12 sectors between 2019 and 2023 found a further decline of 3.4mn jobs… China shares of the export of 10 labour-intensive products — including home fixtures, furniture, luggage, toys and others — peaked at nearly 40 per cent in 2013, according to figures compiled by Hanson at Harvard Kennedy School. Hanson’s figures show that China’s share of the combined 10 goods had fallen to less than 32 per cent by 2018…

Beijing risks experiencing the same “China shock” that it imposed on advanced manufacturing nations after its entry to the World Trade Organization in the early 2000s, when orders migrated en masse from more expensive hubs to the cheap and efficient factories of Guangdong and other provinces. Now, the cheaper factories are in countries like Vietnam and Indonesia where exports have surged… Gordon Hanson, a professor at Harvard Kennedy School… points to the example of Martinsville, in the US state of Virginia, the onetime “sweatshirt capital of the world”, where in 1990 as many as 45 per cent of working-age adults were involved in manufacturing. The majority of those jobs “just disappeared” as the town failed to reposition its economy, he says — and today the poverty rate is double that of the nation.

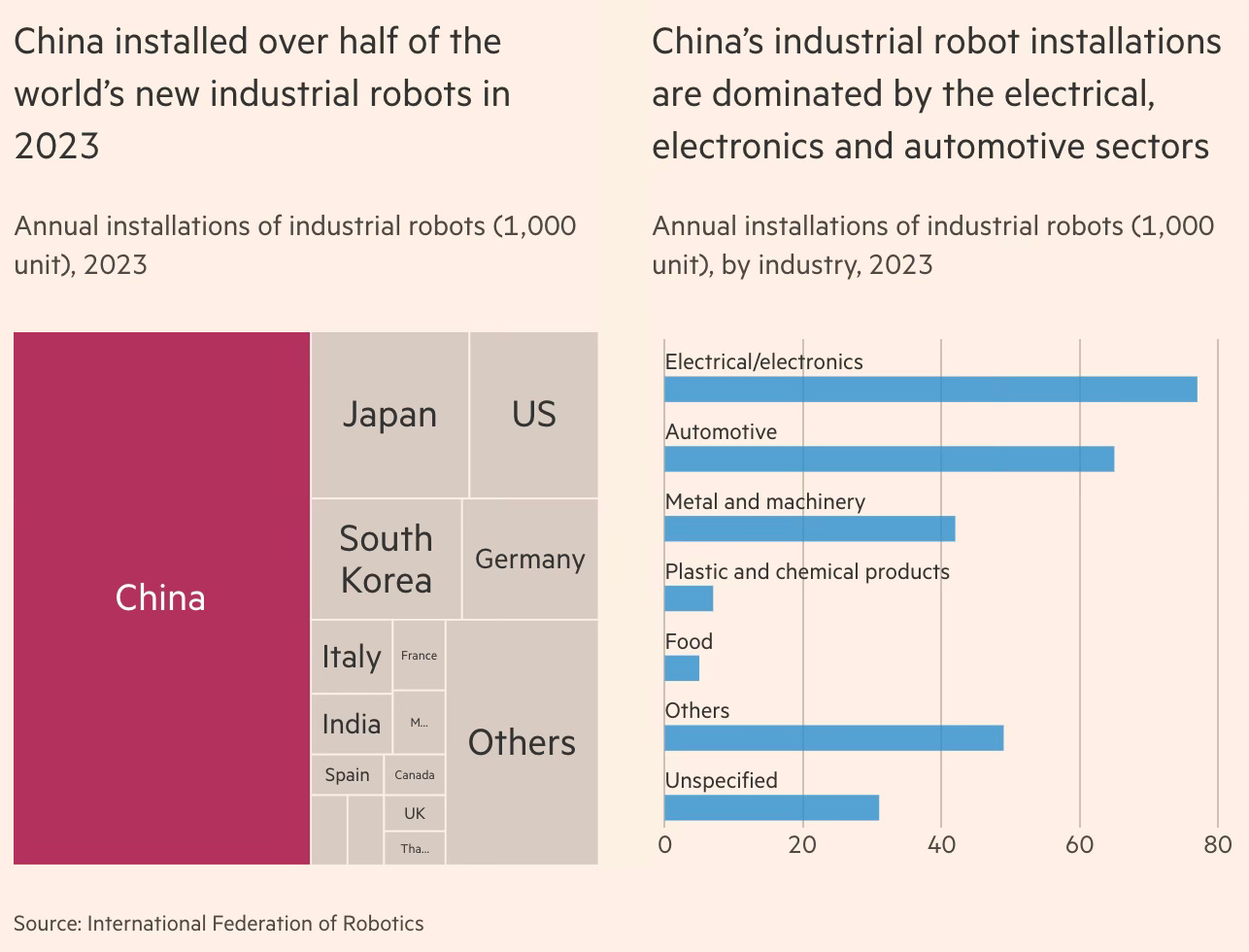

Amidst the declining labour intensity, automation and robots have taken off in China, encouraged by President Xi’s vision of “new productive forces” - high-tech machines run by smart systems to develop sophisticated products. Besides, automation also improves productivity and allows Chinese companies to remain competitive.

Amplifying automation are demographic trends. China’s working-age population peaked at over 900 million in 2011 and is estimated to decline to 700 million by 2050. The decline, coupled with rising education levels, means that youth are reluctant to work on production lines. While all this creates employment opportunities and consumption, the problem is with the large numbers of workers who will be displaced and are not equipped to seize the emerging opportunities.

14. The death of Pope Francis has been accompanied by articles on his legacy. For a start, he was unique in many ways.

The Argentine prelate was the first pope from the Jesuit order, bearer of a centuries-old tradition of challenging authority and operating with relative independence from the Vatican. He was not only the first pope from Latin America and the western hemisphere, but the first non-European pontiff since the Syrian-born Gregory III (731-741). In this respect, his elevation to the Holy See on March 13 2013 reflected the steady movement of Roman Catholicism in modern times from its historical heartland of Europe to the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

More importantly, his 12-year tenure saw intense debates on several important areas like sexual behaviour, clerical morality and the liturgy.

In the last months of his reign, Francis lashed out at the Trump administration’s plans for “mass deportations” of migrants... Another powerful example was his 2015 encyclical, Laudato sì (On Care for Our Common Home), a document that for the first time placed concern for the environment on the same level as human dignity and social justice in Vatican doctrine... If such language was guaranteed to raise the hackles of climate change sceptics, no less heated was the conservative response to Amoris Laetitia (The Joy of Love), an apostolic exhortation that Francis published in 2016. Less authoritative than an encyclical, in that it set out a possible course of action rather than binding Vatican doctrine, this document raised the possibility of allowing divorced and remarried Catholics to receive the sacraments — a significant break with Catholic tradition... Francis came under frequent conservative attack for his decision to reverse a 2007 initiative of Benedict and reimpose restrictions on the celebration of some sacraments according to old Latin rites. Yet Francis was no darling of progressive Catholics, either. Many regarded his approach to issues such as homosexuality and the role of women in the Church as too cautious.

His tenure, however, was widely critiqued among the conservative Maga Catholics in the US who were worried that the reforms were deviating from the Bible and the original teachings. They denounced Francis as a spokesman for a liberal cosmopolitan elite and hope that the death of the pope will mark an end to his reformism.

Distrust of Francis was particularly widespread among the “Maga” Catholics, a group that combines support for Trump’s populist, nationalist agenda with an embrace of Christian orthodoxy and deep suspicion of liberal trends in the church... “Trump has boosted Catholicism by reaffirming some essential things, such as border protection, the defence of human life and the fact there are only two genders,” said John Yep, leader of Catholics for Catholics, a political campaign group. “That was good for Catholics and that’s why 58 per cent of Catholics voted Republican in November.”... Traditionalists were particularly angered by Amoris Laetitia, his 2016 apostolic exhortation, which raised the possibility of allowing divorced and remarried Catholics to receive the sacraments. They also denounced his 2023 decision to approve blessings for same-sex couples, his advocacy of action against climate change and his welcoming approach to migrants. For conservative Catholics who had always been uncomfortable with the reforms of Vatican II, his hostility to the Latin mass was particularly hard to accept.

The rise of MAGA populism among Catholics is an indicator of certain long-term rightward shifts in the US.

“The clergy that has graduated from seminaries in the last 10-20 years [in the US] tends to be more conservative,” said Janna Bennett, chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Dayton, Ohio. She noted the role played by institutions such as the Franciscan University of Steubenville, in Ohio and Ave Maria University in Florida, both of which have a conservative reputation and have provided a pipeline of aspirant priests and lay ministers with a traditionalist mindset. According to a survey published in 2023 by the Catholic Project, a research group at the Catholic University of America, more than 80 per cent of priests ordained since 2020 described themselves as theologically “conservative/orthodox” or “very conservative/orthodox”. The researchers said that while theologically “progressive” and “very progressive” priests made up 68 per cent of new ordinands in the 1965-69 cohort, that number had today “dwindled almost to zero”. It is no surprise, then, that Pope Francis became such an irritant to many American Catholics.

15. Chris Miller makes the case for component-based tariffs in the case of semiconductor chips.

An iPhone might be assembled in China, but most of the key components are from elsewhere. There is a precedent here in watches, where the tariff rate is calculated based on components like batteries and wrist-straps. The Biden administration previously considered imposing component tariffs on Chinese chips, before backing off, worried about the complexity. Yet imposing component tariffs on chips from China — which produces less than 3 per cent of chips in US supply chains — is far easier than imposing tariffs on all foreign chips.

16. Finally, China's policies with its neighbours are an important reason for the hard limits to its influence in Asia. Consider the example of setting up fish farm installations in international waters in the Yellow Sea, which are part of the country's 'grey zone' tactics to bully neighbours in their territorial waters and establish claims.

Chinese companies started building large-scale deep-sea fish farms in 2016 for Norwegian companies raising salmon in the Atlantic Ocean. Construction on the first Yellow Sea installation, the Shenlan 1, began in 2018 in the “provisional measures zone”, a disputed area in the Yellow Sea where Chinese and South Korean exclusive economic zones overlap. It was built by Wanzefeng Group, a fisheries company based in eastern Shandong province. A second structure, the Shenlan 2, was installed last year in the PMZ by a joint venture between Wanzefeng and state-owned Shandong Marine Group, despite Seoul’s protests. South Korea dispatched a marine research vessel last month to investigate but was forced to turn back after an hours-long stand-off... some observers warned that such actions in disputed waters could be a precursor for more solid territorial claims. “They put their fishing vessels and fish farms there with subsidies and infrastructure support, and after a while they use the fact of that presence to underpin a historic claim,” said a senior government official in the Philippines, which has repeatedly clashed with China in the South China Sea.That stance has also been endorsed by some Chinese observers. Current affairs blogger Shijiu Chen Nianhuashe wrote last month: “On the surface, we are building ordinary fish farms. But in fact, this is a smart move to increase our actual control in these disputed waters.” Nam Sung-wook, a professor at the Graduate School of Public Administration at Korea University, said a chain of Chinese structures in the Yellow Sea could ultimately obstruct South Korean or Korea-based US naval vessels from accessing the East China Sea in the event of a conflict in the Taiwan Strait. “We should have taken action sooner,” Nam said. “If any country doesn’t respond to such territorial issues immediately, it becomes a fait accompli.”

No comments:

Post a Comment