The China shock and the resultant Trump tariffs have surely ended the three decades of WTO-based global trade order. It sets the stage for the emergence of a new global trade order. In this context, commentators have pointed to a Mar-a-Lago accord on the lines of the Plaza Accord of 1985. What are the possible contours of the new trade order?

This post examines four proposals and makes certain observations on the way forward.

Since the victory of Donald Trump, two of his close associates have advocated institutional solutions to address the problem of persistent large trade deficits.

Robert E Lighthizer has advocated a new trade regime among countries with democratic governments and mostly free economies to achieve a long-term trade balance. The countries outside the regime will pay a higher tariff while those within would pay lower tariffs, which, however, could be adjusted over time to ensure balance. If a country runs large and persistent surpluses, others would raise tariffs on it so as to bring it down over a reasonable time. This would ensure balance within the entire group over time, and not across country pairs or smaller groups every year.

Stephen Miran has pointed to the dilemma faced by a country whose currency serves as the global reserve currency between maintaining its economic competitiveness and ensuring global liquidity. The global demand for dollars keeps the currency overvalued, which erodes manufacturing and export competitiveness and leads to persistent deficits. To lower the deficit without diminishing the dollar’s global influence, he proposed a deal between the US and its trade partners. The deal will involve the foreign holders of US Treasuries switching from short-term to perpetual dollar bonds, in return for access to the US market and its security umbrella. This monetisation of the American role in the post-war Western alliance is effectively a “protection racket”.

In a Foreign Affairs article, Michael Pettis argues that any sustainable solution to America’s large trade deficit is to “reverse the savings imbalance in the rest of the world” or to “limit Washington’s role in accommodating it”, and that tariffs do neither.

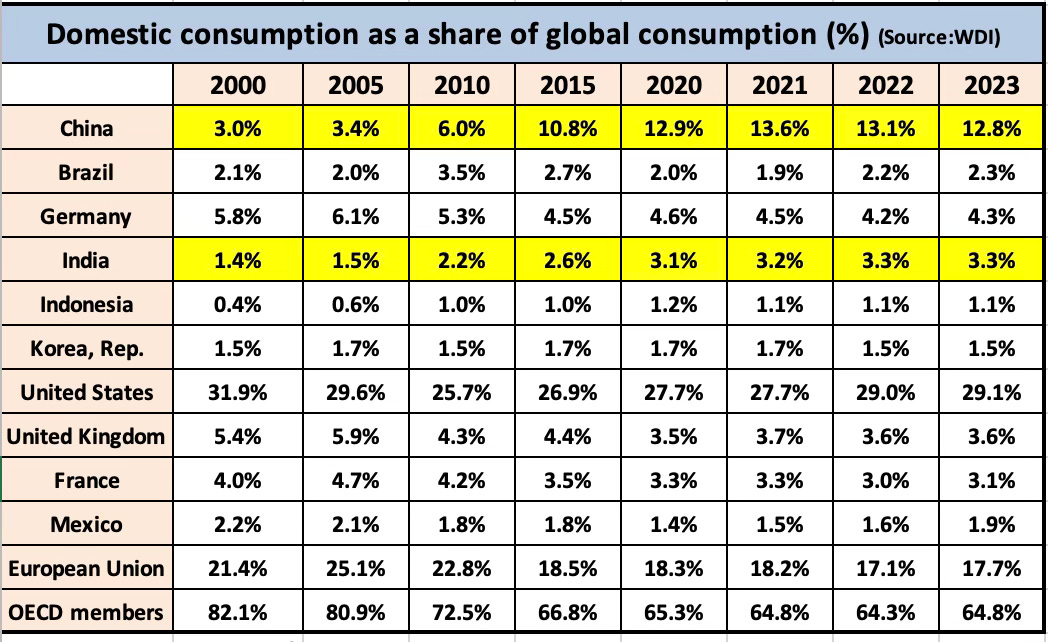

He places the blame for the global economic imbalance on wage suppression in certain countries, which allows them to attract investment and produce far more than their suppressed demand.

Businesses that shift production to countries where labor costs are lower relative to workers’ productivity can produce goods more cheaply, making their products more attractive globally… wage suppression puts downward pressure on domestic consumption while subsidizing domestic production. This results in a rising gap between production and consumption which, if it remains within the economy, must be balanced by raising domestic investment (which can further exacerbate the gap between production and consumption). Otherwise, the gap invariably reverses, either via raising wages or by cutting back on production.

But in a globalized economy, there is another option: running a trade surplus. This allows the country to export the cost of the gap between consumption and production to trade partners. This is why, in 1937, the economist Joan Robinson referred to the trade surpluses that resulted from suppressed domestic demand as the consequences of “beggar-my-neighbor” policies. It is also why, at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, Keynes opposed a global trading system that allowed countries to run large, persistent trade surpluses. A system that accommodated these surpluses, he said, would encourage countries eager to expand manufacturing to subsidize it at the cost of domestic demand. The result, Keynes explained, would be downward pressure on global demand as countries fought to remain competitive by suppressing wage growth. The countries most successful at doing so would become the winners of global trade. Their share of global manufacturing would expand while that of their trade partners contracts.

At the time that Keynes and Robinson were writing, the cost of beggar-thy-neighbor policies came mainly in the form of higher unemployment, as higher exports—unbalanced by higher imports—undermined manufacturers in trade deficit countries and forced them to lay off workers. But after the world abandoned the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s, governments—including the U.S. government—learned to allay the costs of unemployment either by lowering interest rates to encourage consumer lending or through unrestricted deficit spending. The United States thus disguised the employment consequences of running a consistent trade deficit, but it did so through surging household and fiscal debt…

Some major economies exert less control over their domestic economies in favor of more global integration, whereas others choose to retain control over their domestic economies, perhaps by controlling wage growth, or determining domestic prices and allocation of credit, or restricting trade and capital accounts. To the extent that the latter set of states intervene to prevent their domestic economic imbalances from reversing, they effectively impose their internal imbalances on countries that retain less control over their trade and capital accounts. If they choose industrial policies aimed at expanding their manufacturing sectors, for example, they are also implicitly imposing industrial policies on their trade partners, albeit ones that result in a relative contraction in those partners’ manufacturing industries.

If globalization is to thrive, the world must revert to a kind of globalization where countries export in order to import and where a country’s production, consumption, and investment imbalances are resolved domestically—not foisted on to trade partners. The world requires, in other words, a new global trade regime where countries agree to restrain their domestic imbalances and match domestic demand with domestic supply. Only then will states no longer be forced to absorb one another’s internal imbalances.

He therefore proposes a customs union, starting with a small group of like-minded countries that will expand gradually to include more countries.

The best outcome would be a new global trade agreement among economies that commit to managing their domestic economic imbalances rather than externalizing them in the form of trade surpluses. The result would be a customs union like the one proposed by the economist John Maynard Keynes at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944. Parties to this agreement would be required to roughly balance their exports and imports while restricting trade surpluses from countries outside the trade agreement. Such a union could gradually expand to the entire world, leading to both higher global wages and better economic growth…

States that join would agree to keep trade between them broadly balanced, with penalties for members that fail. But they would also erect trade barriers against countries that don’t participate in order to protect themselves from imbalances outside the customs union. Trade would not be expected to balance bilaterally, of course, but rather across all trade partners. Its members would have to commit to managing their economies in ways that would not externalize the costs of their own domestic policies. In that system, every country could choose its own preferred development path, yet it could not do so in ways that inflict the costs of domestic imbalances on trade partners…

Many countries, especially ones that have structured their economies around low domestic demand and permanent surpluses, might initially refuse to join such a union. But organizers could start by gathering a small group of countries that make up the bulk of global trade deficits—such as Canada, India, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the United States—and bringing them into it. These states would have every incentive to join, and once they did, the rest of the world would eventually have to participate.

He also makes the provocative argument that the “US would be better off without the global dollar”.

The most effective way is likely to be by imposing controls on the US capital account that limit the ability of surplus countries to balance their surpluses by acquiring US assets. While this may at first seem to go against current US policy under Trump, who wants to increase foreign direct investment, if done correctly capital controls would in fact have little effect on direct investment. A less effective way is through controls on the US trade account, with bilateral tariffs an especially clumsy way of addressing the root causes of trade imbalances.

The dominance of the dollar in global trade and finance has long been assumed to be a net benefit for the American economy, but this assumption is increasingly being challenged. While it benefits Wall Street and global owners of moveable capital, these benefits come at a cost to American manufacturers and farmers. In a world where some countries actively manage their external imbalances and others do not, the US dollar’s role as the primary safe currency has made America the chief enabler of global economic distortions. Addressing these imbalances requires a fundamental re-evaluation of the rules governing global trade and capital flows.

In another article in Foreign Affairs, Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi offer a very comprehensive proposal to build an alliance against China. They argue in favour of America forging alliances with like-minded partners to create a meta-economy that can outcompete China.

They place China's economic strengths in perspective.

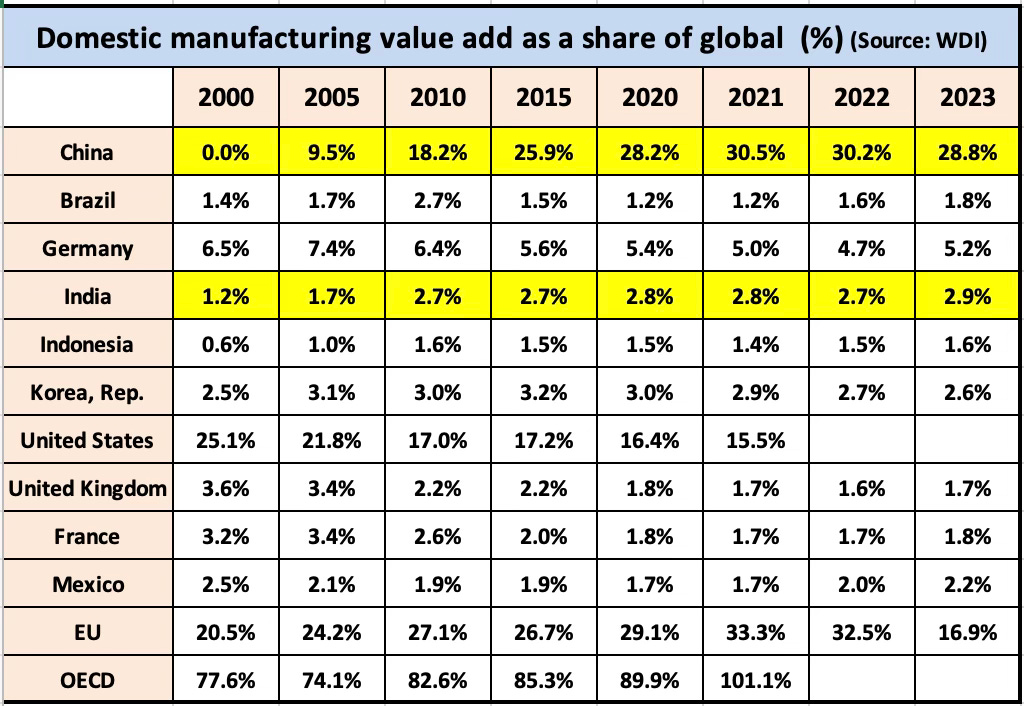

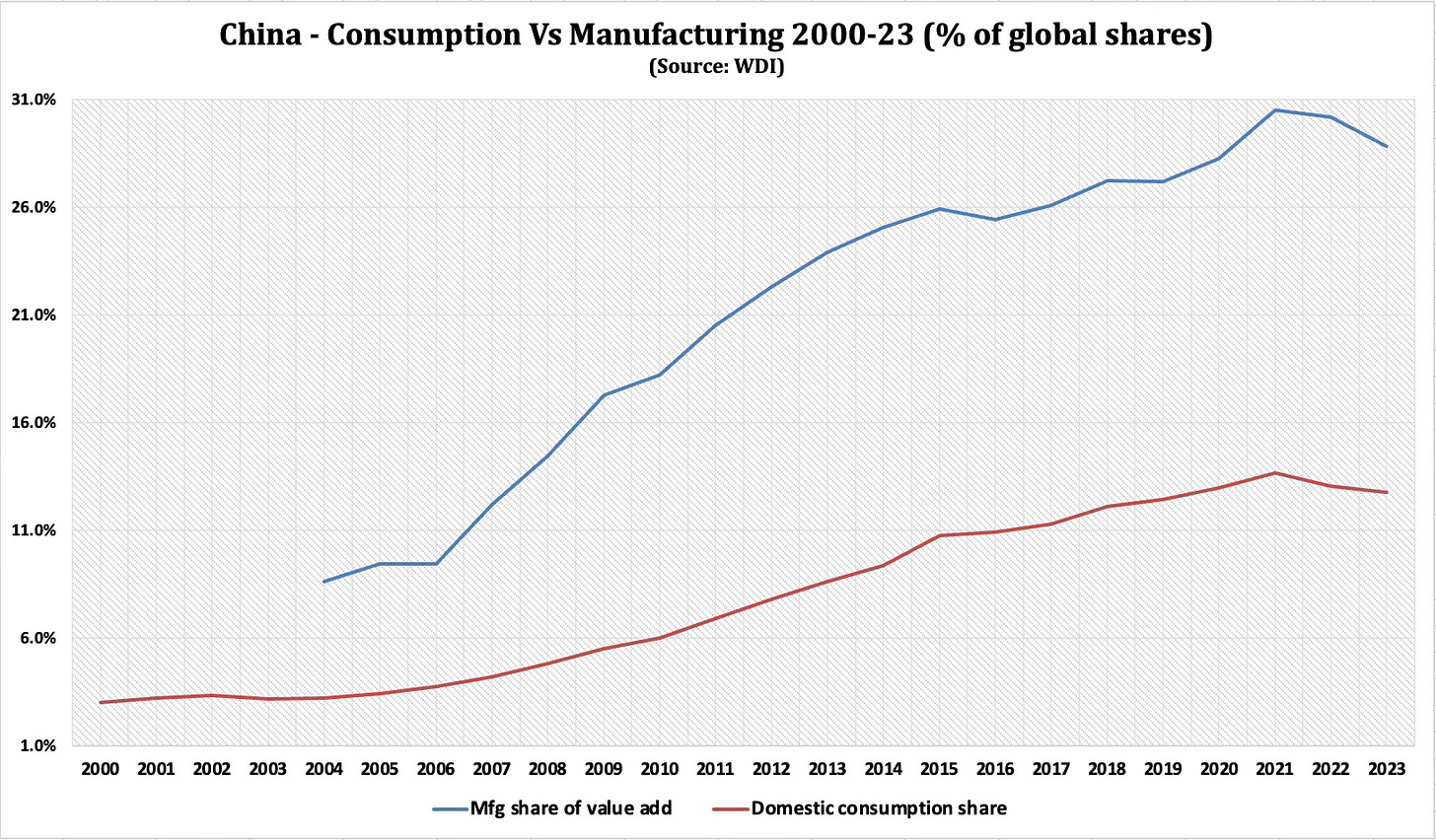

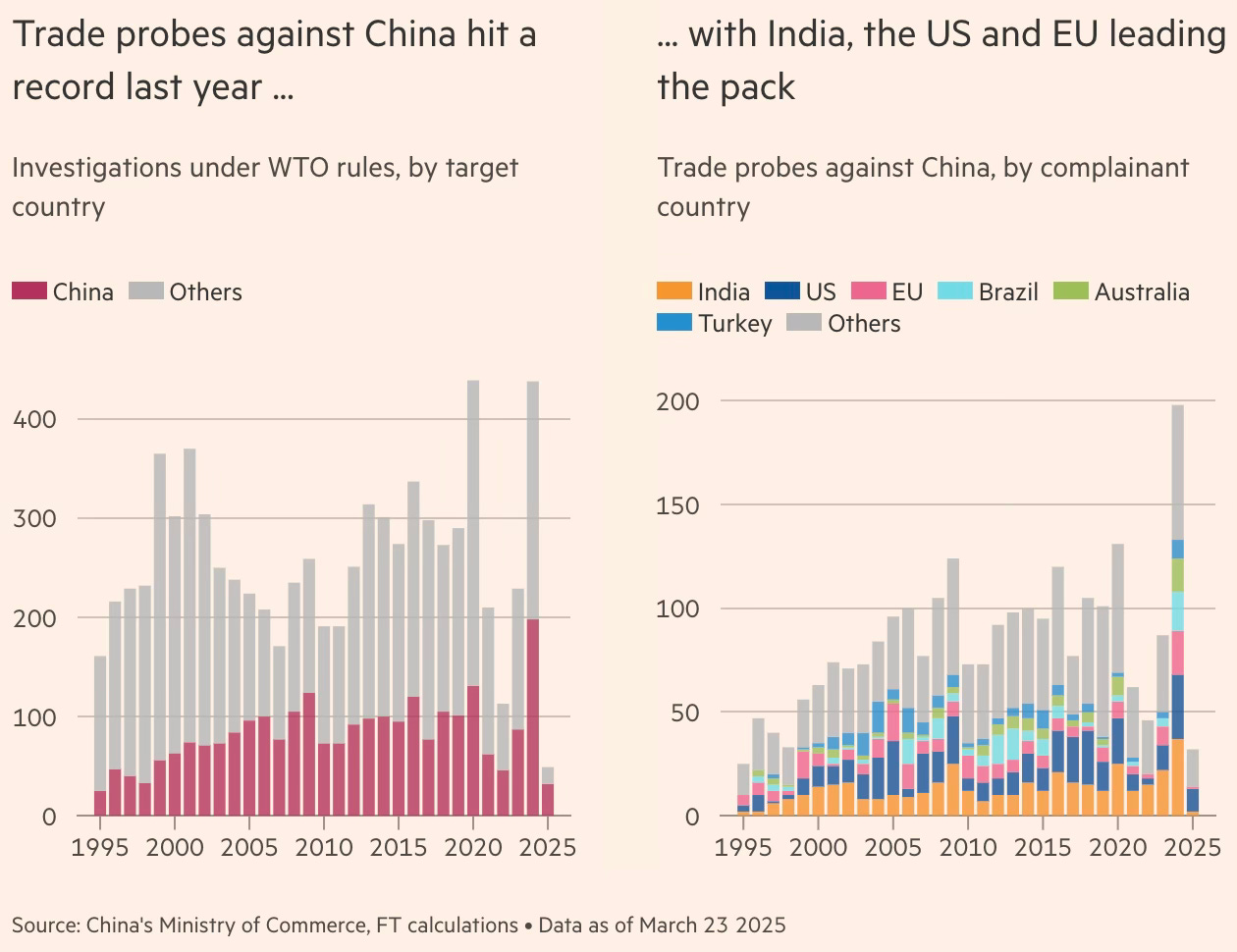

If one looks narrowly at goods rather than services, China’s productive capacity is three times as large as that of the United States—a decisive advantage in military and technological competition—and exceeds that of the next nine countries combined. In the two decades after China joined the World Trade Organization, its share of global manufacturing quintupled to 30 percent while the U.S. share halved to roughly 15 percent; the United Nations has estimated that, by 2030, the imbalance will grow to 45 percent and 11 percent. China leads in many traditional industries—producing 20 times as much cement, 13 times as much steel, three times as many cars, and twice as much power as the United States—and increasingly in advanced sectors as well...

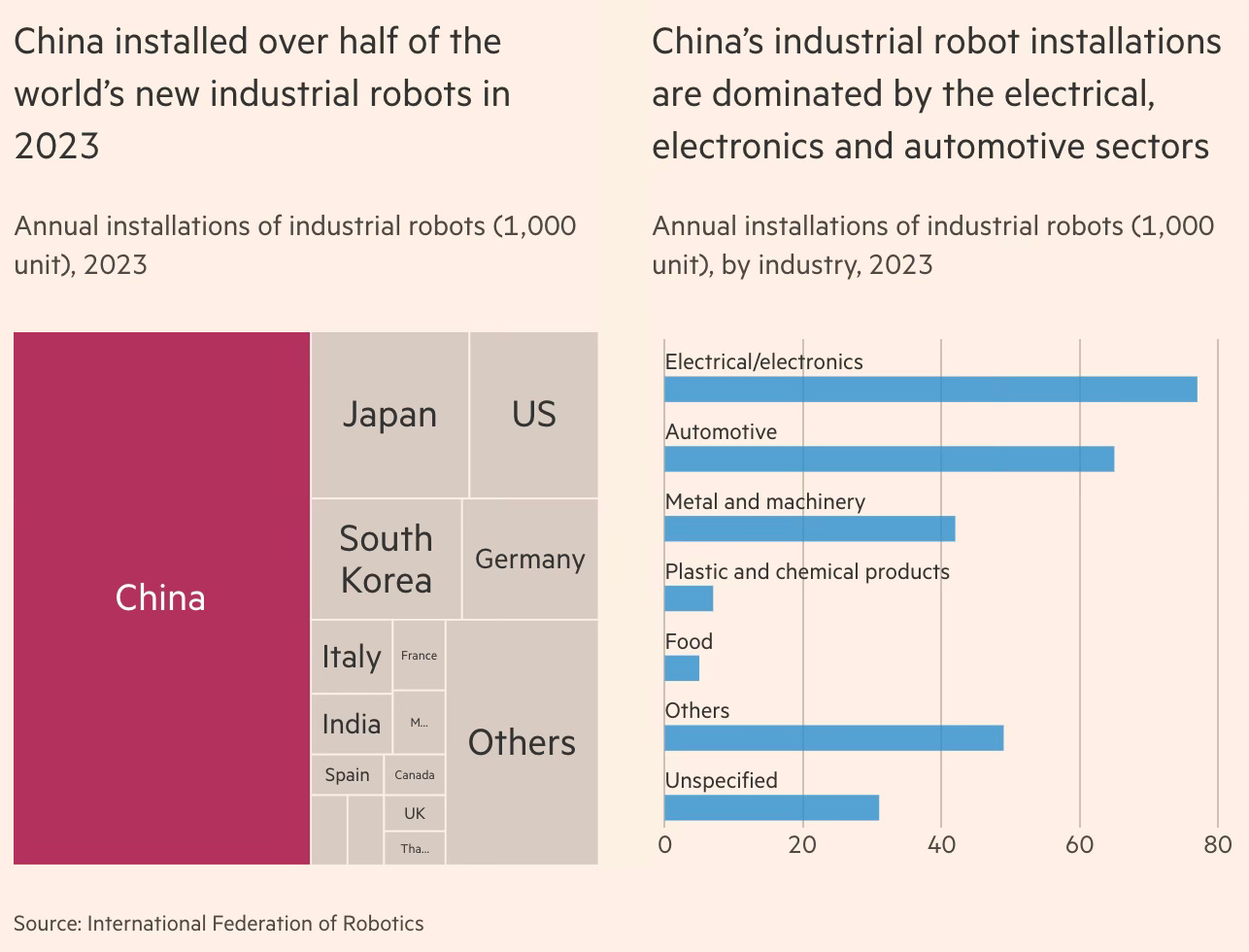

China—thanks in part to ambitious industrial policy efforts such as Made in China 2025—produced almost half the world’s chemicals, half the world’s ships, more than two-thirds of electric vehicles, more than three-quarters of electric batteries, 80 percent of consumer drones, and 90 percent of solar panels and critical refined rare-earth minerals... China was responsible for half of all industrial robot installations worldwide (seven times as many as the United States), and it is a decade ahead of anyone else in commercializing fourth-generation nuclear technology, with plans to build over 100 reactors in 20 years. The last great power to so thoroughly dominate global production was the United States, from the 1870s to the 1940s…

This industrial and innovative strength can be activated for military purposes. China’s navy, already the largest in the world, will add a staggering 65 vessels in just five years, reaching a total size 50 percent larger than the U.S. Navy—roughly 435 vessels to 300. It has rapidly increased its ships’ firepower, surging from one-tenth of the United States’ vertical launch system cells a decade ago to likely exceeding U.S. capacity by 2027. Although China lags the United States in aviation, it has broken a long-standing technical barrier by building jet engines at home and is now rapidly closing the production gap, with the ability to build more than 100 fourth-generation combat aircraft annually. In most missile technologies, China is probably the world’s leader: it boasts the first antiship ballistic missile, impressive air-to-air missile range, and the largest stockpile of conventional cruise and ballistic missiles. And in a growing number of military fields, from quantum communications to hypersonics, China is ahead of any competitor. These advantages, built over decades, will persist even if China stagnates.

They write about the perils of underestimating China.

American observers tend to underestimate China’s ability to innovate, mistakenly assuming it simply copies and reproduces Western innovations. Like the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, and the United States before it, China’s manufacturing strength creates a foundation for innovative advantage. State investment helps, too; it now rivals the United States’ investment in science. And China’s large population provides a deep talent pool and competitive scale. In ten industries of the future, according to a recent report from the Information Technology and Industry Foundation, China is near the leading edge of innovation (or better) in six.

They argue that despite all its challenges, in the medium-term China will be able to manage them enough to remain strongly competitive with the US.

Even if its weaknesses prove more severe than projected, China will remain vastly more powerful than any past U.S. competitor on the metrics most relevant for competition. Washington may have overestimated past rivals, including Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union. But China is the first to outmatch the United States in size alone, as well as in several strategically relevant areas. Stagnant or not, Beijing will remain more formidable than any past challenger.

So what should America do? They argue that America must draw on its vast network of allies to achieve scale and outcompete China.

To achieve scale, Washington must transform its alliance architecture from a collection of managed relationships to a platform for integrated and pooled capacity building across the military, economic, and technological domains. In practical terms, that might mean Japan and Korea help build American ships and Taiwan builds American semiconductor plants while the United States shares its best military technology with allies, and all come together to pool their markets behind a shared tariff or regulatory wall erected against China. This kind of coherent and interoperable bloc, with the United States at its core, would generate aggregate advantages that China cannot match alone...

For Washington, three realities must be central to any serious strategy for long-term competition. First, scale is essential. Second, China’s scale is unlike anything the United States has ever faced, and Beijing’s challenges will not fundamentally change that on any relevant timeline. And third, a new approach to alliances is the only viable way the United States can build sufficient scale of its own. Altogether, this means that Washington needs its allies and partners in ways that it did not in the past. They are not tripwires, distant protectorates, vassals, or markers of status, but providers of capacity needed to achieve great-power scale. For the first time since the end of World War II, the United States’ alliances are not about projecting power, but about preserving it.

During the Cold War, the United States and its allies outclassed the Soviet Union. Today, a slightly expanded configuration would handily outclass China. Together, Australia, Canada, India, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, the United States, and the European Union have a combined economy of $60 trillion to China’s $18 trillion, an amount more than three times as large as China’s at market exchange rates and still more than twice as large adjusting for purchasing power. It would account for roughly half of all global manufacturing (to China’s roughly one-third) and for far more active patents and top-cited journal articles than China does. It would account for $1.5 trillion in annual defense spending, roughly twice China’s. And it would displace China as the top trading partner of almost all states. (China is today the top trading partner of 120 states.) In raw terms, this alignment of democracies and market economies outscales China across nearly every dimension. Yet unless its power is coordinated, its advantages will remain largely theoretical. Accordingly, unlocking the potential of this coalition should be the central task of American statecraft in this century.

In terms of operationalising this alliance, they make specific suggestions.

The starting point for the United States can be long-standing bilateral alliances (such as those with Japan and South Korea) and multilateral alliances (such as NATO), along with newer partnerships (such as the AUKUS defense technology agreement with Australia and the United Kingdom) and less institutionalized groupings (such as the Quad, which also includes Australia, India, and Japan). But rather than simply celebrating these frameworks or expanding their membership, the task ahead is to deepen their function—to make them foundations for capacity-centric statecraft across multiple domains. These relationships have too often operated on the assumption that the United States provides security while others contribute political support or, at best, niche capabilities. It has been largely security-centric, too—focused on deterrence, access, and reassurance—while leaving economic coordination, industrial integration, and technological collaboration as emerging but still secondary concerns. The traditional model was simply not designed to compete with a systemic rival on the order of China. It is dangerously inadequate to the demands of the moment.

The U.S. approach to alliances and partnerships in recent decades has been shaped by a combination of strategic habit and structural hierarchy. Now, it must become a platform for generating shared capacity across all critical domains—not just military ones. That will require a level of coordination and codependence that is unfamiliar and will at times be uncomfortable for both the United States and its partners. For military power, creating scale requires capacity to flow in both directions, including investment in the weaker parts of the U.S. defense industry and more generous provision of advanced U.S. military technologies to allies who historically have not received it. For the economy, scale means building a shared tariff and regulatory wall against China’s excess capacity while constructing new mechanisms to coordinate industrial policy and pool allied market share. For technology, the challenge will similarly be to erect common investment rules, export controls, and research protections to prevent technology transfer to China while undertaking joint investment. These steps mark the difference between a coalition that is aligned in principle and one that is fused in practice. That shift—toward shared capacity as the foundation of strategy—will allow the United States and its partners to compete at scale and at speed…

The United States needs to construct what the historian Arthur Herman has called an Arsenal of Democracies: a networked defense industrial base built on joint production, shared innovation, and integrated supply chains… More ambitious efforts might involve joint ventures with Japanese and South Korean shipbuilders (which are two to three times more productive than U.S. firms); partnerships between Europe’s missile manufacturers and U.S. companies; or recruiting Japanese or Taiwanese firms to build legacy microelectronics in the United States… The United States’ own capability must also flow outward to allies… Sharing technology quickly is the key to ensuring that Australia builds nuclear submarines, that Asian allies have sufficient antiship cruise missiles and ballistic missiles, that Taiwan can deter Chinese invasion, and that India is able to turn the Andaman Islands to its east into a fortress that Beijing cannot ignore. In practice, this could mean harmonizing export-control laws, aligning procurement standards, and coordinating investment in chokepoint components, from semiconductors to optical equipment…

South Korean weapons can help Europe rearm and reindustrialize. French nuclear technology can support India’s submarine program. Norwegian and Swedish missiles can help Indonesia and Thailand defend their waters. Pooling capacity requires thinking across alliances, with the United States facilitating collective action.

This alliance would have geopolitical dimensions…

Globally, the United States could pursue a new version of U.S. President Richard Nixon’s “Guam Doctrine,” which devolved responsibilities to partners after the Vietnam War. That would empower regional states—what former Australian Prime Minister John Howard called “deputy sheriffs”—to take the lead on security challenges in their neighborhood: Australia in the Pacific islands, India in South Asia, Vietnam in continental Southeast Asia, Nigeria in Africa. In practical terms, the next time a South Asian country faces challenges, the United States would defer to India’s judgment on what might serve regional stability or counter China’s influence rather than seek to advance its own preferences.

… and economic dimensions.

Instead, the United States and its allies and partners must find scale together, through a defensive moat against Chinese exports. Building a protected common market could start with coordinated tariffs on Chinese goods. But because tariffs can be easy to circumvent, a better approach might be to use coordinated nontariff barriers, including regulatory tools… Another tool is “preferential plurilateralism”—selectively opening allied and partner markets while creating higher barriers for Chinese goods. This approach, broadly supported by figures across the political spectrum, from Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. trade representative during Trump’s first term, to prominent Democratic legislators, echoes aspects of the early post–World War II trading system, which gave preferential treatment to members of the free world over autocratic rivals. If the era of free trade agreements is over for now, then sectoral agreements with allies could offer promising avenues for pooling markets while avoiding political sensitivities. Coordinated industrial policy instruments would also be useful, such as a new international industrial investment bank that would make loans to firms in strategic sectors to diversify supply chains out of China, especially in key sectors such as medicine and critical minerals. And coordinated efforts to remove barriers to allied and partner investment could, for example, allow the bypass of national security review.

A few observations:

1. All four proposals mentioned above have a common feature. They require the mobilisation of allies and, effectively, the creation of a new alliance against China. I’m not sure that, after all that has happened in the last 100 days, the Trump administration has the capital, much less the inclination, to mobilise this alliance. It would want an imperial alliance with it at the centre, with the vassals surrendering to its hegemony. The Plaza Accord and other instances of Western alliance did not emerge under such hostile circumstances.

I’m not sure of any kind of Mar-a-Lago accord being done and implemented in good faith during the Trump regime. However, it’s quite possible that if the Trump administration wreaks havoc on the world economy and is succeeded by a Democrat President, it might trigger a cathartic mobilisation among the US and its allies. That might be the Overton Window to create a new global trade order. However, it’s most likely that the Trump administration’s policies would have created irreversible norms in areas like decoupling from China, the reshoring of US manufacturing, and burden sharing on defence by allies. Most importantly, it would have stigmatised the practice of egregiously subsidised export-led growth. This may well be the best outcome to hope for.

2. The proposal made by Doshi and Campbell is comprehensive and is the ideal configuration. Their case for an alliance among like-minded countries to combat China’s scale is particularly important and even an essential precondition for any meaningful effort to combat China’s manufacturing dominance. It would be a throwback to the immediate post-war era of alliance-building and collective commitment to combat communism and the Soviet Union. Here, though, the primary objective would be to create the economic scale in markets, supply chains, and manufacturing to outcompete China.

It would also be a full-scale open declaration of Cold War 2.0 between a new alliance of democracies led by the US and another of autocracies led by China. Perhaps this ideological framing, with all its associated values, can be the glue to mobilise and cohere this new coalition.

3. Even if an alliance materialises, the operationalisation of any proposal to continuously pursue balanced trade among allies will itself be an immense challenge. The distortions arising from such complicated forced incentives can be unpredictable and self-defeating. Perhaps the biggest political economy challenge would be in getting countries to exercise voluntary self-restraint and raise tariffs. Why would emerging economies voluntarily give up their comparative advantages and forego one of their major drivers of economic growth and job creation?

4. If trade deficit is the issue, then why should it be confined only to merchandise trade and exclude services trade? Would the US force its Big Tech and Wall Street firms to exercise similar self-restraint and refrain from exporting their services to other countries and running up large trade surpluses?

5. As mentioned earlier, merchandise trade deficits cannot be seen in isolation and are a function of the stage of development (Engel’s law) and structure of the economy, its comparative advantage, and the role of the US Dollar as the global reserve currency. If the US wants to continue its exorbitant privilege (unlimited borrowing in its currency), then the dollar (and Treasuries) must be the global reserve currency and (therefore) default safe-haven asset, and it should not be averse to running large trade deficits. This effectively means that the US cannot achieve a trade balance without also balancing capital flows, which comes in the way of its role as the holder of the global reserve currency.

6. The US multinational corporations and technology firms have been among the biggest beneficiaries of globalisation and the dollar’s role as a reserve currency. A major share of their benefits has come at the cost of the US domestic manufacturers and the American labour. It’ll be America’s political choice on whether it wants to enjoy the exorbitant privilege by continuing policies that support Big Business at the cost of labour or reconcile itself to a reduced role for the US dollar with policies of the kind advocated by the likes of Michael Pettis.

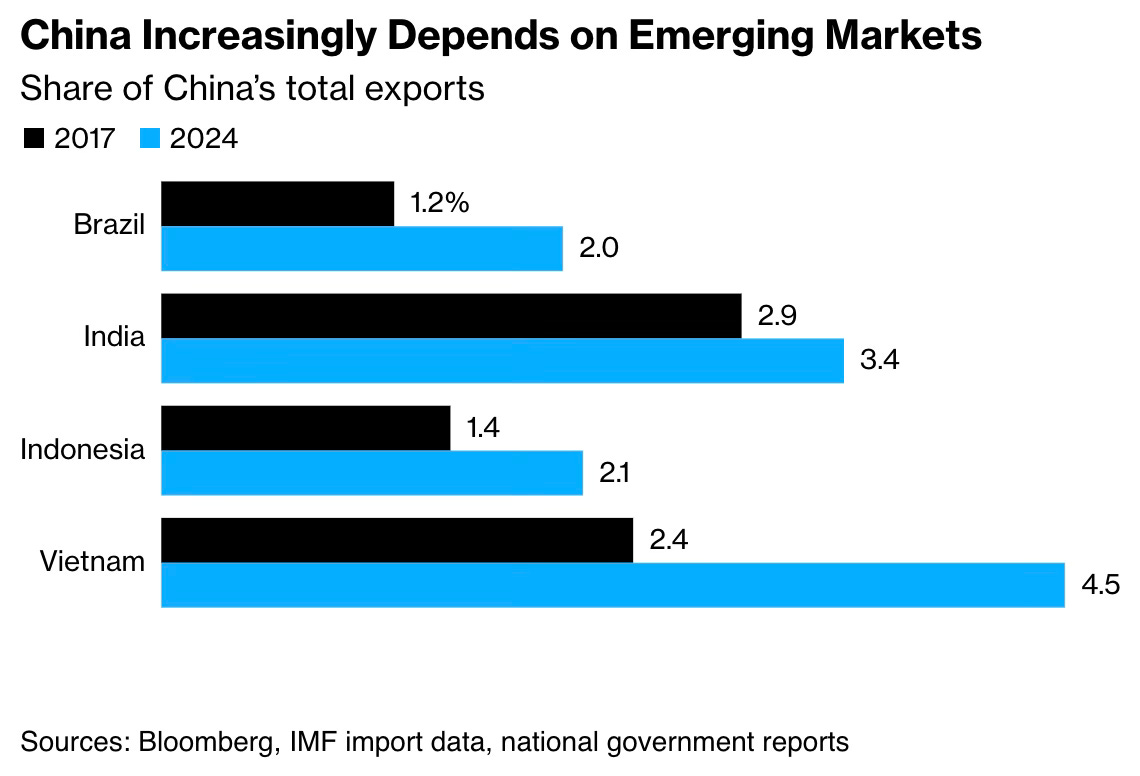

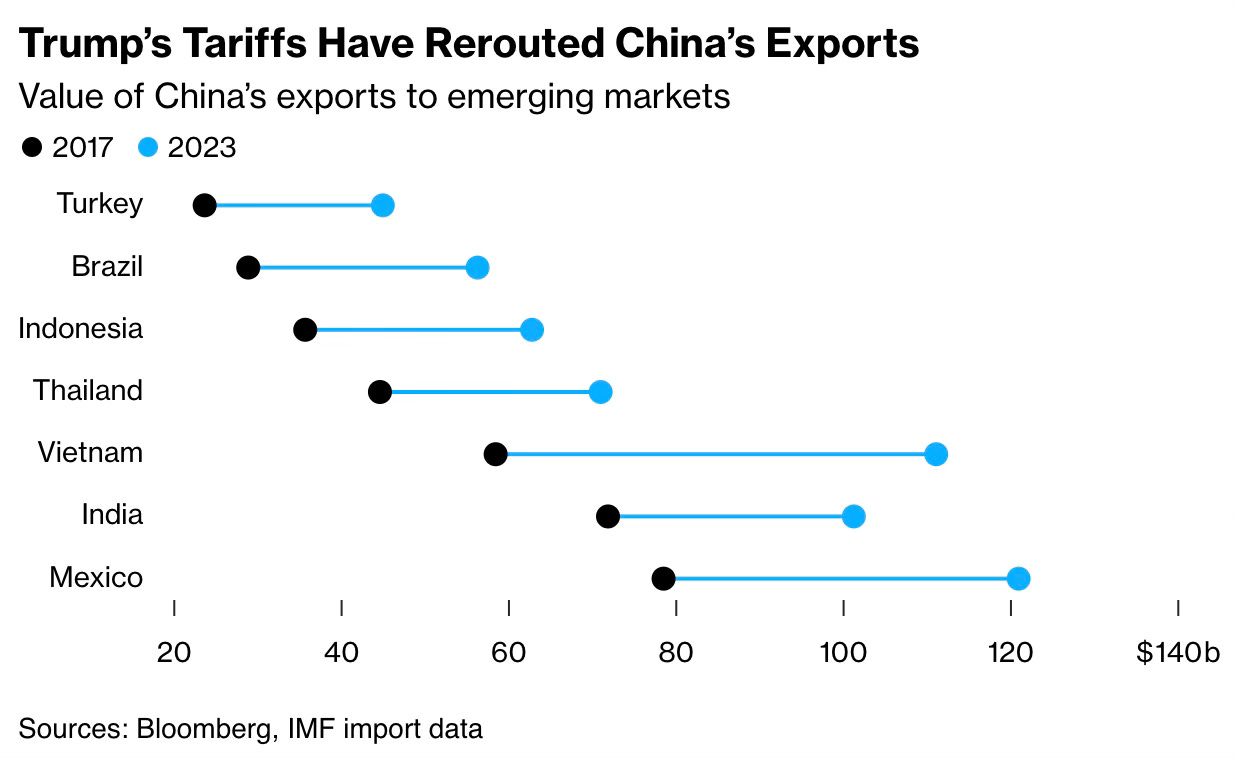

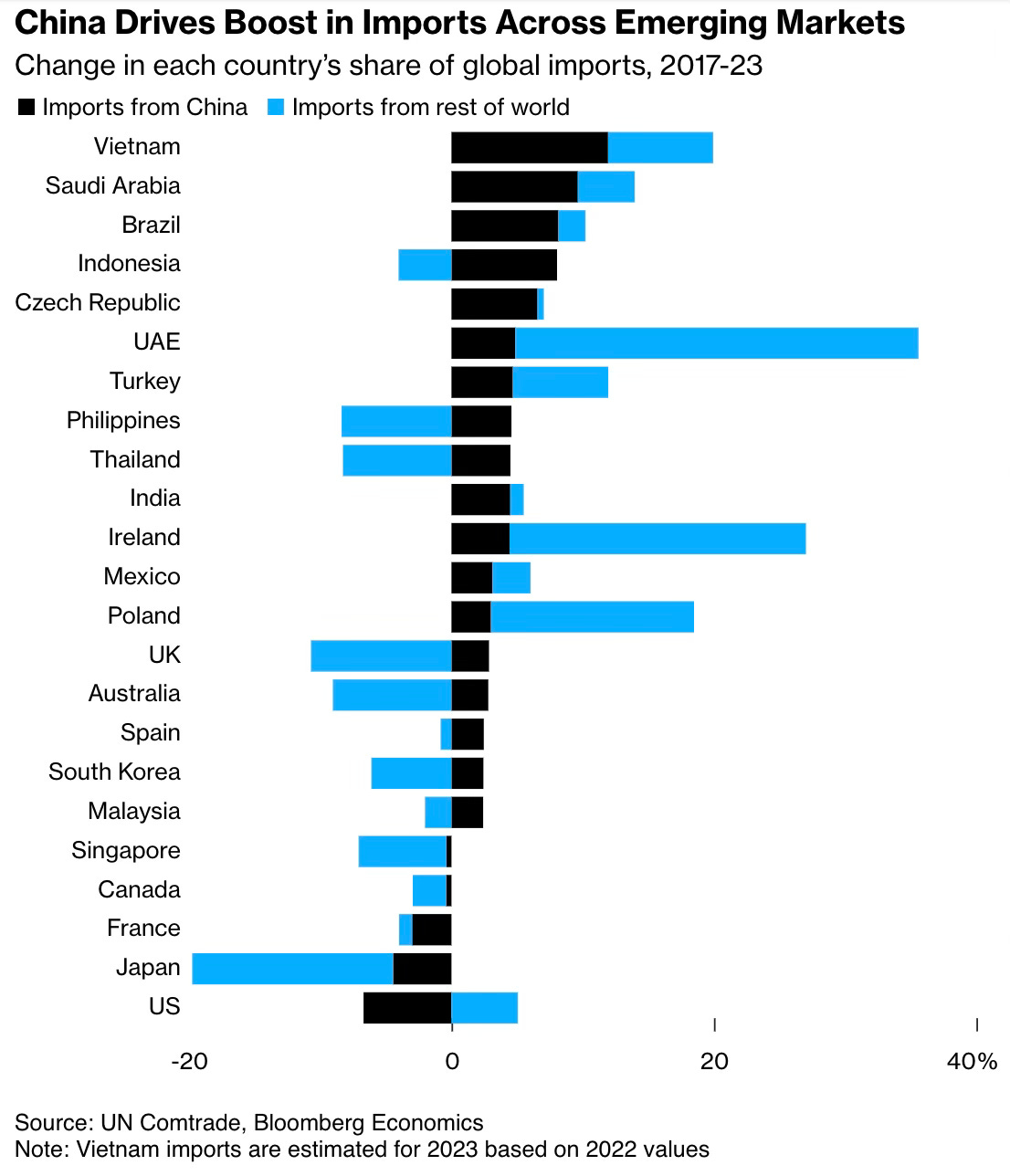

7. It’s common to find an idea itself becoming discredited due to its unbridled or unqualified pursuit or poor execution. China leveraged the forces of outsourcing and unbundling of supply chains, advances in ICT, the long period of global economic and political stability, trade liberalisation, and the emergence of the WTO and its membership there to push the boundaries of trade and manufacturing. Its state-directed capitalism used a combination of economy-wide repression (of wages, financial markets etc.), massive subsidies, and disciplined industrial policy to pursue manufacturing and merchandise trade dominance at a staggering and unprecedented scale.

Its consequences for the world economy have been devastating, not only in destroying the manufacturing bases globally but also in discrediting the very idea of comparative advantage and global trade that has been one of the main sources of post-war economic prosperity. The Trump administration’s single-minded focus on imports and trade deficits owes almost entirely to China’s beggar-thy-neighbour trade policy.

8. Developing countries like India should be careful not to lock themselves into a trade deal that centres on balancing bilateral trade deficits. India’s aspiration for sustained high growth is critically dependent on exports. The US is the world’s largest market, and it’s natural for emerging economies to run merchandise trade surpluses with developed economies. The proposals of Lighthizer, Miran, and Pettis do not even acknowledge these realities and instead propose a one-size-fits-all trade balancing.

If India’s manufacturing push succeeds, it’ll invariably run large surpluses with the US. For example, if Apple decides to source all its 60 million US iPhones from India, that alone will significantly increase India’s trade surplus with the US which is already reasonably high at around $40 bn even without too much manufacturing exports. Add in more such exports from the reconfiguration of other supply chains, and it’s most likely that India emerges among the top five countries with which the US has a trade deficit. Will it then not require India to try to balance Therefore, it cannot bind itself to a treaty that caps its trade balance with the US.

One tactical approach would be to ride out the Trump regime. It could target an opportunistic trade deal with the Trump administration without committing to any long-term binding targets. A tactical deal to buy time for a comprehensive bilateral or multilateral deal in four years!

9. India’s trade negotiation strategy is also weakened by its recent trade policies involving increased tariffs and non-tariff barriers (like the Quality Control Orders). President Trump is right in some ways in calling it the “tariff king”, at least among the major economies. It will now have to make significant concessions in many sectors in terms of liberalising its trade policy.

This immediately creates two problems. One, on the economic side, having raised high protective barriers, even a normalisation of tariffs and removal of the recently erected non-tariff barriers would be a step change and abruptly expose the domestic manufacturers to foreign competitors. Two, on the diplomatic side, since negotiations are going on with others, most notably the EU, there will be pressure from them to offer the same terms given to the US.