There’s a rich body of literature on the natural resource curse faced by low-income countries, especially in Africa. Not only does the mineral-rich country fail to capture value from its resources, but also the exploitation of the resource ends up weakening its economy (Dutch disease) and polity (corruption).

I have blogged here and here in the context of Guyana’s windfall from its discovery of Stabroek oil block off its coast and how it triggered a development versus climate change debate. It also highlighted the issue of limited value capture and contractual exploitation by Exxon Mobil.

In this context, FT has a long read on how Indonesia took control of its nickel resource, a mineral critical for energy transition uses like in EV batteries and in smartphones and other electronics, and forced domestic value capture. In 2014, it banned the export of raw nickel ore and forced processors and refiners to establish factories in Indonesia.

The decision encouraged Chinese companies, led by steel giant Tsingshan Holding Group, to spend billions of dollars to set up processing plants in Bahodopi and across other parts of the south-east Asian country of 281mn people. Today, Bahodopi is home to the world’s largest nickel processing site: Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park. Majority owned by China’s Tsingshan, the park spans over 4,000 hectares and has dozens of nickel smelters and steel plants, as well as its own port and airport…

Before 2014, most of Indonesia’s nickel ore was sold to nickel and steel manufacturing plants in China… a total ban on exports of nickel came into effect in 2020 under then President Joko Widodo setting the stage for Indonesia’s nickel boom. Huge investments came from Chinese steel, nickel and battery manufacturers, including Tsingshan, CATL and Lygend, who partnered with Indonesian mining companies to set up processing facilities. Chinese stakeholders control over 75 per cent of Indonesia’s refining capacity, according to a recent report by C4ADS, a Washington-based security non profit. Not only did the companies bring capital, they also brought the knowledge to process Indonesia’s low-grade nickel reserves quickly and profitably… The Chinese had made advancements in rotary kiln electric furnaces, which turns nickel ore into raw material for steel. They had also mastered the high-pressure acid leach technology, a refining process that converts low grade nickel ore to battery-grade — a procedure that western companies had struggled with for years…

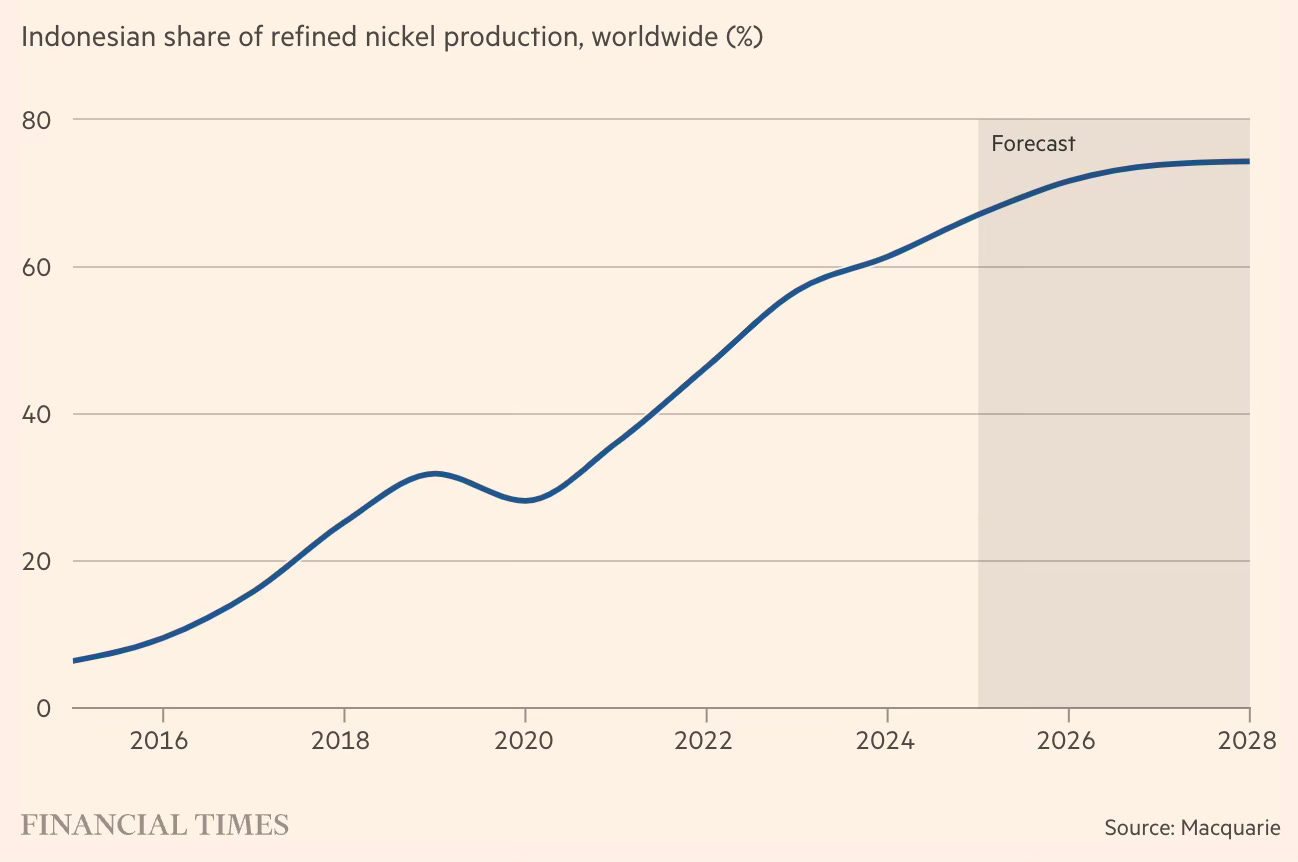

The transformation is a remarkable turnaround for a country that a decade ago was not even a major player in nickel. Although Indonesia held the world’s largest reserves — about 55mn tonnes as of 2024, according to the US Geological Survey — most of it was low-grade nickel that it had not yet figured out how to process efficiently. But with the help of Chinese technology, huge investment from Beijing and a dose of protectionism, Indonesia has gained control of the market and cemented itself as the epicentre of global nickel production for years to come. Last year, Indonesia accounted for 61 per cent of the global refined nickel supply up from just 6 per cent in 2015, according to Macquarie, the Australian bank and asset manager. Its market share is expected to grow to 74 per cent by 2028. This means Indonesia now controls more of the world’s supply of nickel than Opec did of oil at the cartel’s peak in the 1970s — then around half of global crude oil output.

This dramatic growth has prompted some complaints. European governments have accused Indonesia of using excessive protectionism, while Indonesian nickel has been criticised for being “dirty” due to deforestation and the use of coal-fired plants, claims that Indonesia disputes… But the export ban garnered global criticism and was challenged at the World Trade Organization by the EU, which argued the restrictions were unfairly harming its stainless steel industry… It has also created a conundrum for Western countries trying to build any critical mineral supply chain without Beijing.

Indonesia’s dominance of the market has shaken up the global nickel industry.

For the global mining industry, this whirlwind growth has raised concerns over supply concentration — and the consequences of any possible disruption. Surging production in Indonesia has wiped out competition from companies such as the Australian mining group BHP and dramatically reshaped the global supply chain. By flooding the market and driving down prices, the Sino-Indonesian partnership has made it much harder for rivals to produce the metal economically elsewhere in the world… Nickel mines elsewhere in the world owned by western companies tend to be older, less efficient and more expensive to run, analysts say. They also rely on more expensive labour as well as higher costs of capital.

Meanwhile, Chinese companies can build smelters quickly and hit full capacity within a year or less, while western companies take roughly three to five years or more. In other words, Indonesia’s explosive growth has been the undoing of the rest of the industry. Its rapid expansion has driven down nickel prices to below $16,000 per tonne. BHP, once one of the world’s largest nickel producers, is among the miners that have closed their nickel operations, blaming a “significant oversupply”. Australia’s Wyloo, run by billionaire Andrew Forrest, has also closed mines, while Brazilian firm Vale has launched a strategic review of its nickel assets in Thompson, Canada, including a possible sale. “Over 10 to 15 per cent of the rest of the world has gone out of business,” says Lennon. According to his estimates, Indonesian production rose by 1.5mn tonnes between 2020 and 2024, while the rest of the world fell by 500,000 tonnes.

Interestingly, the demand for battery-grade nickel being produced in Indonesia may be confined to western EV makers since the Chinese EV makers prefer to use Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) batteries in their EVs.

This is a good case study on the issue of value capture from the primary sector. Some observations:

1. The Indonesian government's decision to ban the export of raw nickel and mandate its processing is the kind of decision that resource-rich developing countries should be encouraged to make. If only more of those countries elsewhere could summon the courage to make these decisions. In less than a decade, it has transformed the economy of the mining region and provided Indonesia with invaluable strategic power.

The original decisions were heavily criticised by the US and Europe and their mining firms. However, instead of criticising the Indonesian decision, they should have applauded it. The Widodo government did what very few developing countries generally tend to do and deserves the credit for making the decision.

2. The decision was only the first step. The real challenge was to establish processing facilities and ensure value capture. This involves convincing investors to develop processing facilities and providing them with the enabling infrastructure and other support. Indonesia was fortunate that there were Chinese firms with both expertise and interest in such investment opportunities. Ideally, Indonesia should have entrusted the processing to a domestic firm or one with a majority domestic shareholding.

In such cases, the biggest challenge faced by countries is their failure to extract even-handed contractual terms from private firms. Corruption and power imbalance are the main reasons for smaller developing countries being forced into exploitative contracts with private foreign (and also domestic) firms. As we discussed earlier, Guyana’s contract with Exxon was loaded in favour of the latter. It’s only to be hoped that the Indonesian government’s contract with Tsingshan Holding Group gives the country fair returns and enough strategic control.

3. The Western mining giants like Vale and BHP, who are now crying hoarse, had the opportunity to invest in Indonesian mines after 2014. While I’m not aware of any details, it’s most likely that the Indonesian government would have reached out to potential investors. Tsingshan, with the active financial and diplomatic support of the Chinese government, would have reached out and offered the best terms. It’s most likely that the US foreign policy was oblivious to the importance of securing access to this strategic resource, and the Western firms were short-sighted and wanted more favourable terms. In any case, the Chinese were opportunistic and bagged the contract, and with it, access to a critical mineral.

It’s a good example of how China has come to exercise control over critical minerals across the world. They were both alive and opportunistic to seize all such investment opportunities, whereas the US and allies preferred to look the other way.

4. It’s now for Indonesia to do whatever is required to tighten control over the asset and leverage this control in its foreign policy. Specifically, it should guard against Chinese controlling the supply chain of the processed mineral. While the contract’s financials are already baked in, the host country surely has enough leverage to tighten its control over the supply chain. Especially since Indonesia is a large enough country and also has the appetite to do so.

It’s also important for the US and allies to negotiate with Indonesia to gain a foothold on the supply chain of the processed mineral and prevent it from being controlled by China. As a start, Tesla could be nudged into investing in an EV battery manufacturing facility in the country. The Indonesian government has been courting Tesla without success.

No comments:

Post a Comment