This post is meant to be a summary of several posts on development. It seeks to illustrate the fundamental issues of development by examining the activities and tasks of four departments.

Consider the fundamental question facing government officials in a few departments.

What’s required to achieve student learning outcomes and create a skilled and employable workforce? What’s required to deliver good quality public health and sanitation to prevent epidemics, maternal and child health, and diagnostic-cum-treatment services? What’s required to improve crop productivity and raise farmer incomes? What’s required to ensure hassle-free access to good quality municipal facilities and services?

Education, Health, Agriculture, and Municipal Administration officials must figure out the answers to their respective fundamental challenges and then execute them.

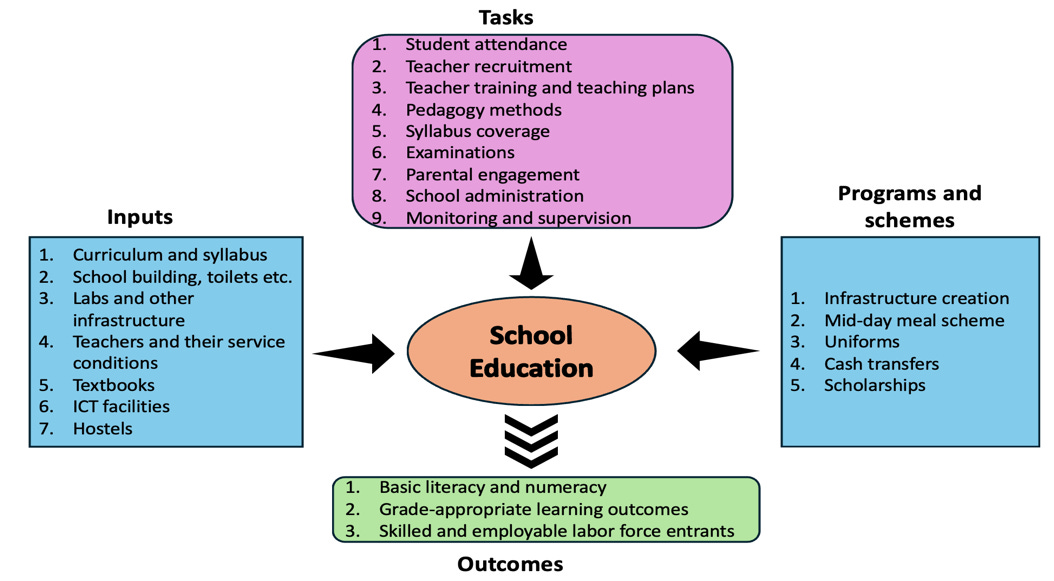

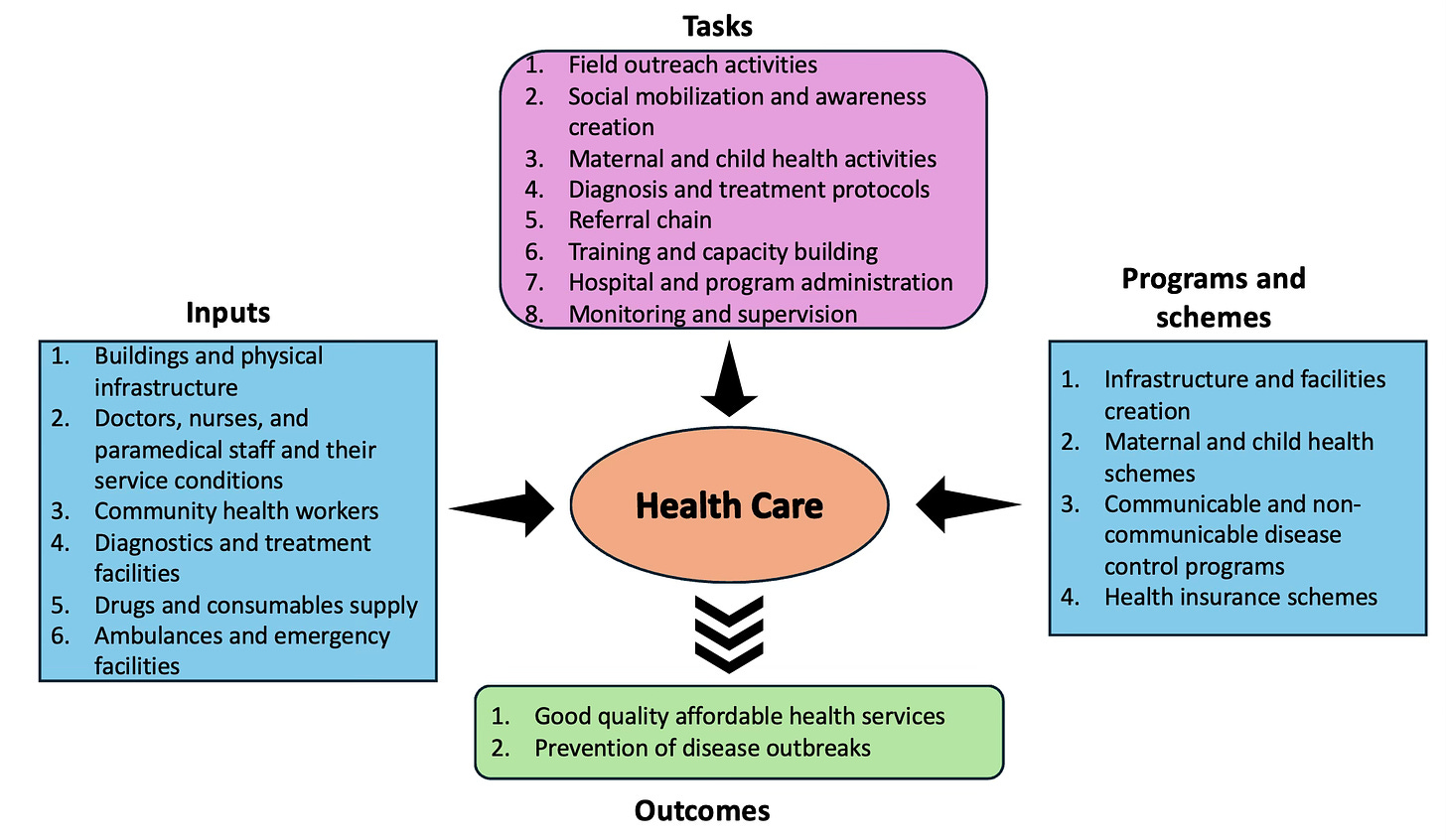

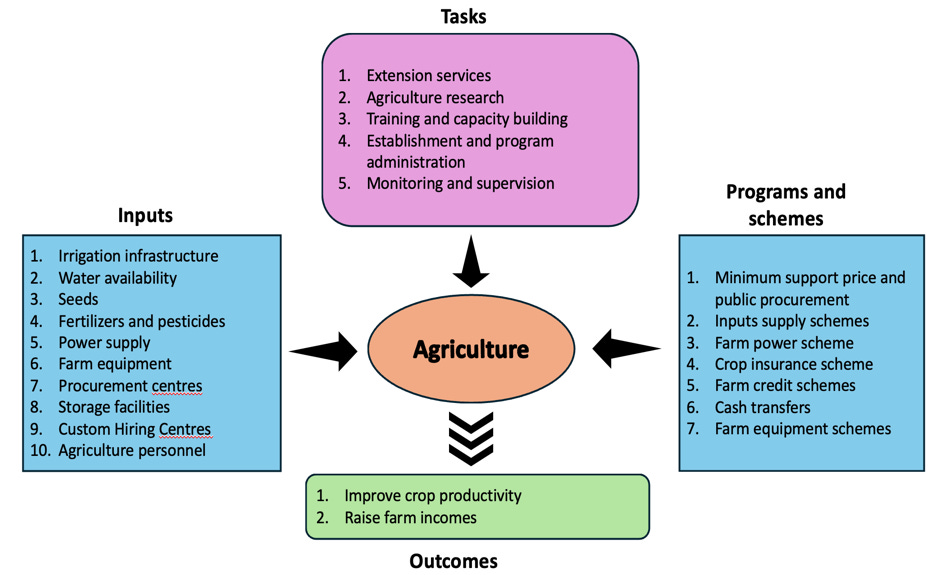

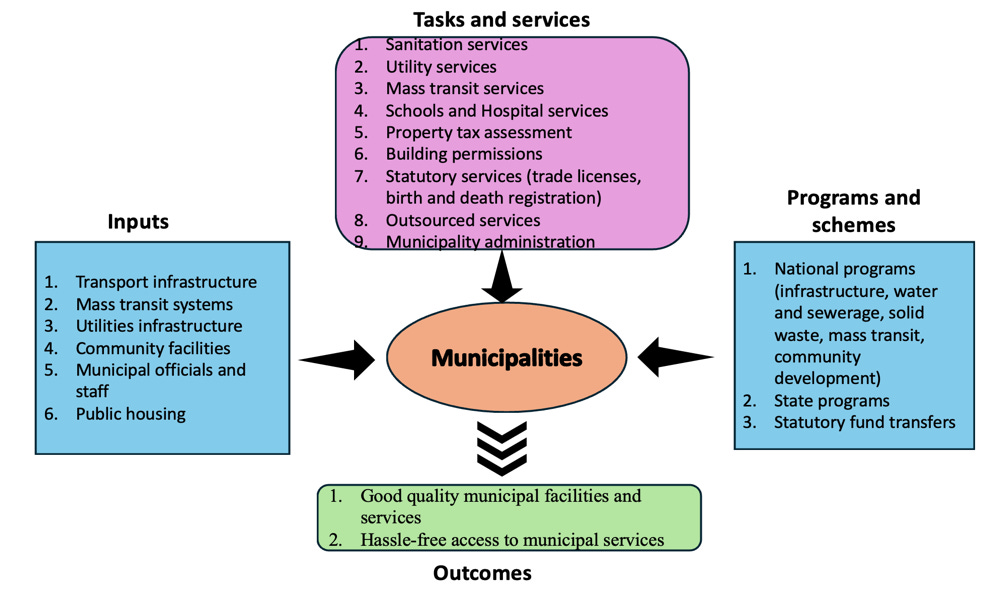

Let’s use a framework to analyse each sector. Government departments apply inputs, including those from programs and schemes, and undertake a set of tasks. The department’s theory of change is that their effective combination would lead to its desired outcomes.

Accordingly, Figure 1 lists the school education department's inputs, programs and schemes, and tasks.

Figure 1: School Education Department

Figures 2-4 do the same for Healthcare, Agriculture, and Municipal services.

Figure 2: Primary and Secondary Health Department

Figure 3: Agriculture Department

Figure 4: Municipal Administration Department

While these are just four samples, they form a major part of the development landscape. Their features broadly represent development in general, across developed and developing countries.

An examination of the lists in each case reveals some important insights. One, despite all the changes in the world around us, the lists of inputs, programs, and tasks in each sector are both universal and have remained the same over a long time. Two, any program and scheme generally contribute some of the inputs to the departmental tasks. Third, a set of activities/tasks combines all the inputs and programs in some manner as specified (based on the theory of change) in their implementation guidelines. Fourth, the effectiveness of implementation is critically dependent on how these activities/tasks are executed. Finally, it’s assumed that all these activities/tasks can be executed effectively through the standard bureaucratic administration, with its associated monitoring and supervision.

Given their centrality to effective public service delivery, it's useful to examine closely the nature of these activities/tasks performed by departments. Four points come to mind.

For a start, close examination would reveal that most of these activities/tasks are basic enough, but complicated by their interaction with the context and the dynamics that emerge from that interaction. Two, the nature of these activities/tasks is such that they generally require high engagement by government officials. In other words, the quality of the performance of these activities/tasks depends on the quality of engagement by the relevant officials.

Three, related to the previous point, there’s only so much that improvisation and technology can do to commoditise or simplify the activities/tasks such that they can be delivered without compromising quality. Finally, notwithstanding this limitation, the effectiveness of implementation can be enhanced, mostly only at the margins, with improvisation and innovation like process reforms and the use of digital and other technologies.

All these have some important implications for development thinking.

One, the scope or possibility for new programs or improvements to the design of existing programs (or generally new ideas) that can significantly improve outcomes is limited. Two, instead, the primary role of innovations and new ideas would be to improve the fidelity of implementation. But there are clear limits to how much they can contribute. They cannot cover up for deficiencies in governance and state capabilities. Three, the primary focus for the administration of these departments should be on the effective execution of its activities/tasks and its programs and schemes. This is all about implementation by government officials through public institutions.

Fourth, in the circumstances, the primary role of evidence is to enhance the effectiveness of implementation. This means administrative data, surveys, and qualitative feedback are important instruments. Finally, given the nature of these activities/tasks, the effective implementation of many of them involves problem-solving, iteration and adaptation, management of people and activities, and exercise of good judgment. All these are activities/tasks that require high individual and institutional capability levels.

No comments:

Post a Comment