This post will make certain specific recommendations to bring financial discipline to India’s electricity sector.

Arguably, the biggest obstacle to bringing financial discipline within India’s power sector is the opacity of financial accounting, especially in discoms. This accounting problem starts with the regulatory award, runs through subsidy allocation in the budget and its actual release, and climaxes at the capital and operating expenditures accounting and their financing. It’s therefore natural that any meaningful reform of the sector address this central problem.

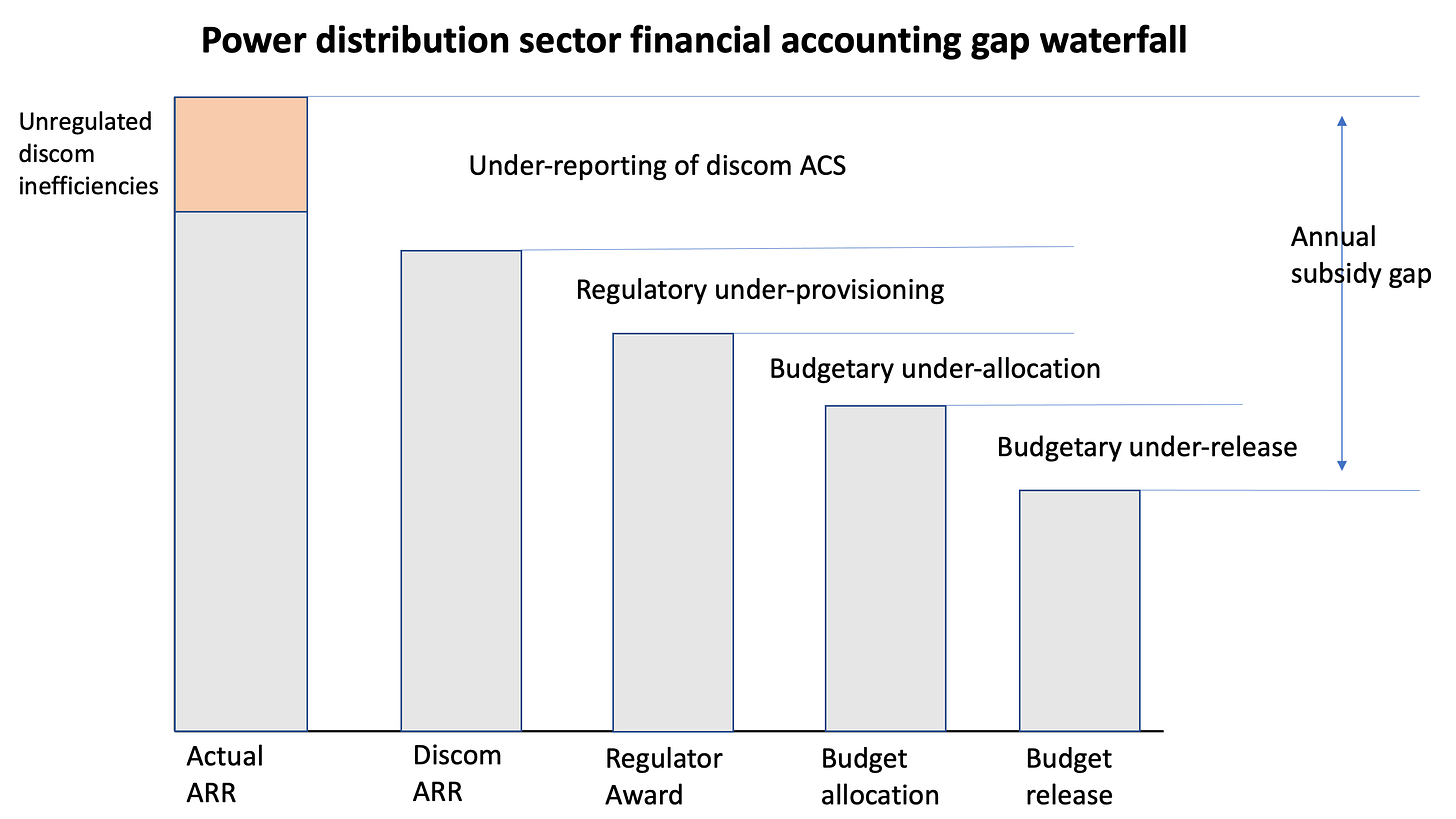

To start with, there are four important but less discussed subsidy-related factors that impact the financial sustainability of Discoms:

a. Under-reporting of subsidy requirements through non-disclosure of the full subsidy requirement by the discoms to regulator

b. Regulatory under-provisioning of the subsidy by the regulator in their annual tariff awards on the informal directions of the government

c. Budgetary under-allocation by the government on the regulatory award

d. Under-release of even the under-allocated amount

As a summary of the process of subsidy determination, the discoms make their Aggregate Revenue Requirements (ARR) filing to the Regulator based on all their expenditures. At the same time, expected revenues are computed based on projected sales and the tariffs determined in the previous year. The Regulator uses the ARR and expected revenues to arrive at the revenue shortfall. Thereupon, based on the subsidy commitment from the state Government and the Full Cost of Service (FCS) principle, the Regulator determines tariff for the coming year.

The discoms, dictated by the government, tend to boost their ARR by inflating the consumption of their subsidizing consumers and deflating that of their subsidized consumers. In their filings, the discoms also try to suppress the gap between the FCS and ARR so that they do not put pressure on the state governments to either allow tariff increases or provide the additional subsidy. They also boost the availability of power from cheaper Hydro stations and suppress the quantum that they would buy from more expensive stations. Their filings also either do not provide or under-provide for the emergency purchases that they would invariably make from the market to tide over spurts in demand.

The under-reporting by discoms complements similarly distorted incentives on the regulatory side. Often, the regulator is gently nudged by the state government on its tariff intentions. In its efforts to confine the award to the government’s requirements, the regulator’s tariff award typically suffers from three problematic assumptions:

a. Over-estimation of the categories of the cross-subsidizing consumers (like commercial and HT consumers)

b. Under-estimation of cross-subsidised consumers like agriculture

c. Under-estimation of total consumption

The net effect of this is a lower subsidy requirement. However, in reality the differential between the actually realized revenues and the tariff award revenues every year would invariably be much higher.

This under-award is compounded by the increasing practice of state governments under-provisioning on the regulator’s award in the budget estimate. Then there is the practice of state governments not releasing even the budgeted amounts. In addition to under-release of subsidies, there is also the problem of inordinate delays in the payment of current power bills by government entities – urban and rural local bodies, public institutions like schools and hospitals, and government offices.

The net result of all these is the significant gap between the actual subsidy and the allocated subsidy, and actual subsidy requirement and the actual releases. The former is absorbed as unregulated losses, and the latter as unregulated debt. The former piles up and corrodes the discom’s balance sheet, while the latter (or a major part) becomes off-balance sheet borrowing of the government.

Finally, this opacity in accounting also comes in the way of fixing accountability. The regulated debt is clear enough. But the unregulated debt combines the under-provisions and under-releases by the government as well as the discom’s own losses and inefficiencies (especially due to free farm power) plus the accumulated interest arrears on these. In the absence of farm power metering, disaggregating the two becomes difficult and discoms commonly add all losses beyond what they desire to project into agriculture consumption.

The cascade of under-provisioning allows the government to abdicate responsibility for a large part of the unregulated debt. In turn, the discom can suppress its AT&C losses, and blame the government for its financial problems.

Debt management

The combination of all these four is a major cause for the continuously growing pile of Discom debts. In order to meet their working capital requirements arising from these under-provisioning and pending receivables, and avoid having to make budget provisions for the gaps, state governments encourage discoms and gencos to take working capital loans with or without government guarantee.

These loans which are generally repaid over time by the government, are effectively state government’s off-balance sheet debts. This arrangement allows state governments to undertake revenue expenditures on subsidies without having them show up in the budget accounts.

This is a continuous cycle – discoms take loans, accumulate debts, and roll them over. Over time, it becomes difficult to segregate the debt into the government and discom’s shares. Once the accumulated pile of debts become unsustainable, Government of India steps in with some restructuring package. This creates moral hazard all round – discoms are disincentivized from efforts to reduce their losses and inefficiencies, and governments from ending the practice of under-provisioning and under-releasing. Over the last two decades, without acknowledging these critical financial accounting issues, different central governments have announced reform packages to restructure the loans. The results have been predictable.

The regulator allows the gencos to assume capex and opex loans. In contrast, the discoms are restricted to assuming only capex loans. The refundable advance that discoms take from consumers is assumed to be sufficient to meet their working capital requirements.

The opacity in accounting, distortions arising from state government guarantees, and inadequate regulatory oversight have allowed discoms to assume large working capital loans and both companies to divert their loans for purposes other than its intended use. It’s essential to put in place regulatory safeguards at both the electricity companies and at the financial institutions to control these bad practices.

It does not help that Discoms have access to a continuous and easily accessible supply of lightly regulated loans from institutions like Power Finance Corporation (PFC) and Rural Electrification Corporation (REC), and public sector banks, who do not monitor the deployment of funds and turn a blind eye towards diversion of the loan amount. The PFC and REC have emerged as the dominant lenders to the discoms and gencos, capturing over two-thirds of the total loans and most of the incremental debt. The state government guarantee and the high interest rates chargeable (lender’s market) make this a captive source of very attractive and easy lending for these power sector development finance institutions. Their inefficiencies too get hidden in the opaque accounting system.

The Discoms also transfer their dues from the government onward to the state-owned Gencos who too access these loans and pile up debts. In fact, this readily available loan spigot of PFC/REC becomes the sink for most inefficiencies in the sector.

Any meaningful attempt to take the power sector to a sustainable pathway should address these issues.

Financial management prescriptions

In light of all the above, in order to improve the financial management of the discoms in particular and the sector at large, the following are proposed:

a. The CERC should issue detailed guidelines to limit under-reporting of their aggregate revenue requirement by the discoms. A standardized ARR estimation format, which builds on the actual expenditures in the previous years, can form the basis for this.

b. The CERC should consolidate the information on ARR, regulatory awards, budget allocation, and budget estimates from all states every year, and make the information available on its website. All actual expenditures should also be collected head-wise at the end of the financial year.

c. The regulatory under-provisioning can be addressed by clear guidelines from CERC that standardise the method for calculation of estimates of consumption. Since the tariff filings are done in the third quarter of the financial year, it’ll not be possible to have the actuals of the previous year to calculate the estimate for the next year.

Instead, the consumption trends for each category from the audited annual accounts of previous years should form the basis for all consumption estimates for the regulatory award. One approach would be to take the estimates for the last five years and then use the compounded annual growth rate for the past five years for that category to calculate its consumption estimate for the ARR (the actuals of H1 and estimate of H2 with an increase based on CAGR over the past five years). This removes discretion from the exercise.

d. The Ministry of Power and CERC, and SERC, too should consider only the regulatory award and actual power consumption or expenditure, not the budget estimate, as the basis for determining the state’s power subsidy obligation. GoI may consider adding these clauses to the National Tariff policy.

e. Accordingly, for example, the state government should reimburse this amount to become eligible for the additional borrowing limit made available as per the Fifteenth Finance Commission recommendations. If the state govt does not provide the subsidy in advance, as is required, a mechanism to automatically bill at actual rates should kick in.

f. The state government should be made accountable for the difference between the subsidy requirement in the regulatory award and the actual budget release. If the budgetary allocation is lower than than the Tariff Order, SERCs should be directed to revise the tariffs suo-moto to make good the deficit. This may be made part of the National Tariff policy.

g. Further, it’s required to monitor how discoms are meeting this financing gap. This should be explained by the state government in its disclosure before the borrowing calendar is announced. If financed through any form of off-balance sheet borrowings, the same should be deducted from the state’s annual open market borrowing ceiling for the coming year.

h. The state government should reimburse the Discoms the full subsidy through regular monthly payments, at the beginning of the month. SERCs should be mandated to take up suo-moto tariff revision every quarter based on actual flow of subsidy, through a direction in the National Tariff policy. The subsidy account for each year should be closed by the end of the year. Non-payment of the monthly subsidy in advance should result in punitive actions like reduction in the state’s net borrowing ceiling.

i. As a corollary requirement, the discoms should prominently state in their audited annual accounts as to whether it has assumed any un-regulated debt on behalf of the state government. The certification in this regard should be the personal responsibility of the Director Finance and the CMD of utility company.

j. The financial institutions too should consider only the subsidy requirement estimated in the regulatory award (itself calculated as above). Any under-provisioned amount in the budget should be accounted as dues receivable from the state government. This information should be used in all credit assessment decisions of financial institutions.

k. Discom dues to Gencos should be subjected to the same terms as that to NTPC. All the dues should be cleared at the end of each financial year, and the same certified in the accounts of both Discom and Genco, on the personal responsibility of the Director Finance and the CMD of the company. In the alternative, the regulator should be compelled to increase tariff without any option.

On the debt management side, the ultimate objective should be to ensure that companies can raise institutional finance only for purposes allowed by the regulator and the debt raised is utilised for the intended purpose. This needs work on the management of both capex and opex loans.

a. PFC and REC should be regulated by the RBI on the same lines as private sector NBFCs. The end-use of loans made by PFC and REC should be closely monitored by the FIs and strong action taken in case of diversion. Presently, such monitoring of end-use of funds is practically non-existent. These institutions should also have prudentially rigorous state and state-sector exposure limits which are strictly enforced.

b. All capex loans given to the companies by financial institutions could be routed through a PFMS like system, whereby the money gets transferred directly from the lending agency to the supplier or contractor, upon certification by the borrower. The discom would operate the account and determine the releases, though any recipient should necessarily be the registered end-use supplier/contractor. To start with, this could be implemented for all REC and PFC loans, and then extended to all banks.

c. In case of opex loans, ensuring accountability on lending and end-use is more difficult. One option is to completely bar discoms from assuming opex loans and restrict gencos to only permissible opex loans. However, its implementation poses difficulties and it can also become too restrictive. A more feasible option in this regard is to permit borrowing for opex loans only upto the limits allowed by the SERCs and CERCs as per the tariff determination process. In any case, the lenders should have visibility into the opex commitments and cash flows of discoms by mandating that discoms should have only one account to transact on all operating receipts and expenditures. The opex lenders should have visibility into the trends in this account and the nature of opex commitments. This will allow lenders to make clear data-based decisions on the pricing and sanctions of their opex loans.

d. The RBI should issue a clear guidance on what kinds of opex debts can be financed by financial institutions, and what should not be financed (accumulated losses, under-provisions and under-releases etc).

The steps mentioned above should be complemented with accurate measurement of farm power to arrive at the correct assessment of AT&C losses.

No comments:

Post a Comment