This post will examine the challenges of controlling inflation at a time of recurrent supply shocks arising from geo-political tensions, de-globalisation, climate change, pandemics etc.

First a bit on the ongoing debate about the central bank’s role in lowering inflation.

I have blogged here earlier expressing caution at attributing the reduction of inflation to central bank actions. The BIS’s recently released annual report endorsed the view that central bank actions were responsible for the rapid disinflation and ensuring financial market stability. Chris Giles has an excellent article, where he first points to the BIS’s endorsement of central banks

Central banks have risen to the challenge. Their forceful and repeated responses to financial stress stabilised the system and limited the damage to the economy. The shortfall of inflation from targets always remained contained. And following vigorous global tightening of the policy stance, inflation is now again returning to the price stability region while economic activity and labour markets have proved resilient… The post-pandemic experience with inflation has shown once again one of the major strengths of monetary policy. In particular, it has highlighted how forceful monetary tightening can prevent high inflation from becoming entrenched. It has also confirmed central banks’ determination to avoid a repeat of the experience of the Great Inflation of the 1970s.

Giles writes that while the BIS’s model about the drivers of US inflation finds a very large role for inflation expectations, those of IMF and others find a very minor (even negligible) role for inflation expectations.

Martin Sandbu points to several other links in an article that refute the claims of central bank actions lowering inflation and instead argue that the public collectively internalised the belief that the energy price shocks etc., would be temporary.

In particular, he warns against drawing the inference that the general response to an inflation episode induced by a supply shock like the energy supply squeeze should always be to raise rates. He points to the work of Bruegel’s Lucrezia Reichlin and Jeromin Zettelmeyer. They examined the challenges associated with formulating monetary policy in an environment of inflation volatility driven by supply shocks and other structural changes (geo-political events, climate change, pandemics etc.).

It’s difficult to judge how central banks should respond to negative supply shocks (which increase prices while reducing purchasing power). The conventional wisdom is to do nothing initially and tighten only if there’s a danger of a wage-price spiral.

They point to four reasons why the approach followed in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine may not be the most appropriate response - supply shocks can steepen the supply curve (firms face higher marginal cost), thereby making inflation more susceptible to shifts in demand; supply constraints can impact sectors asymmetrically, and the adjustment will involve changes to relative prices which can take longer; contrary to orthodoxy (which believes monetary policy acts only on demand and leaves potential output growth unaffected), tightening may dampen investment and innovation and reduce productivity, thereby impacting medium and long-term prospects; and tightening can slow down the energy transition.

In light of these, they make three recommendations

There is a need to establish a framework for flexible inflation targeting in which the time horizon for reaching the objective is linked to the cost in terms of secondary objectives… Depending on whether it helps or hurts the secondary objective, the return to price stability could be accelerated, or the ECB could be patient… Relative price changes have an impact on the optimal level of inflation targeting. In a realistic situation in which prices are sticky, systematic firm-level productivity trends imply higher optimal trend inflation and therefore a higher inflation target… To allow the ECB to do this without risking a loss of credibility – as may occur if the inflation target is seen as ‘following’ actual inflation – it would be advisable to revise the numerical inflation target regularly, based on a calendar established in advance...

Sluggish aggregate demand driven by contractionary monetary policy may penalise green investment and slow the energy transition. Given the ECB’s primary mandate, the appropriate response would not be to rely on monetary policy alone but rather to design an appropriate monetary-fiscal mix with targeted fiscal policy offsetting the undesirable effects of price-stabilising monetary policy. From a policy-design perspective, the ECB should consider the combined effects of monetary and fiscal policy on prices, productivity and whether green investment happens in sufficient amounts… Better coordination among fiscal authorities and/or a larger EU budget would help but this is politically difficult.

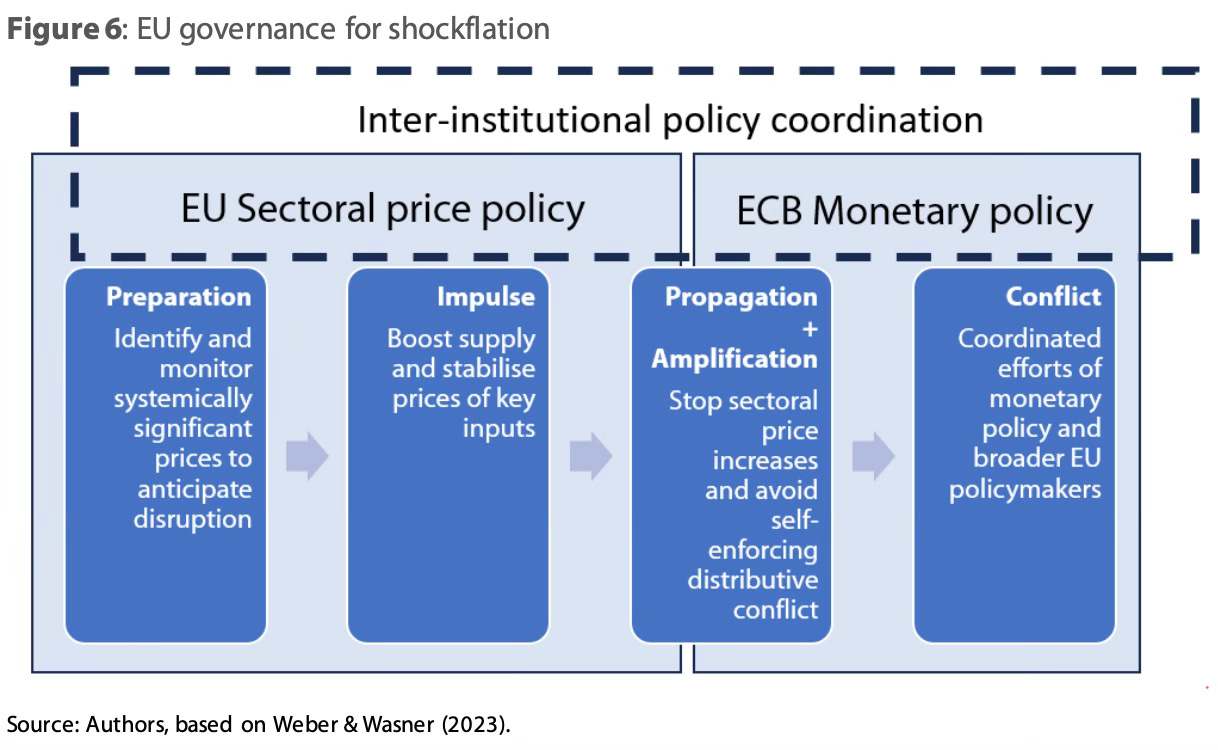

In a report to the European Parliament on how the EU should deal with shockflation (inflation unleashed by shocks to systemically significant prices such as energy and food), Jens van’t Klooster and Isabella Weber argue that the ECB’s monetary policy is inadequate and suffers from an “inflation governance gap”. They worry that the orthodox approach of tightening when faced with inflation from recurrent supply shocks will adversely impact the EU’s ability to meet its public and private investment requirements to combat climate change. They propose that EU “should develop a new inflation governance framework that targets shocks to systemically significant prices directly, before they are propagated through the economy”. Their summary is as follows:

Monetary policy has limited traction on firm price-setting, making it a costly and ineffective instrument to bring down consumer prices in a context of shockflation.

To stop firms from propagating and amplifying sectoral shocks, a new EU-level inflation governance framework should anticipate disruptions where possible and intervene as early as possible.

Eurostat and the ECB’s Datawarehouse should develop an enhanced price monitoring system.

For essential sectors such as energy, food and critical raw materials, the Commission should coordinate Member State policies at the EU-level to avoid impulse shocks as well as boosting supply with physical buffer stocks, stabilising prices with virtual buffer stocks and capping prices when corrections of supply shortfalls and market overshooting are not sufficient.

Competition policy to address price gouging and taxes on windfall profits to stop the proliferation and amplification of shocks should be implemented by the Commission and national competition authorities.

Coordination between the Council, the European Parliament and the ECB should serve to align inflation governance across the different sectors of the European economy.

Immediate monetary tightening to control inflation induced by supply shocks risks hurting investment, innovation, and productivity, thereby imperilling medium to long-term economic growth. Instead, there’s a need for close monitoring, using a heterodox toolkit of policy measures, supplementing with fiscal policy, and coordinating with the multiple stakeholders involved. All this should be wrapped up in a robust governance framework.

The crux of the matter is the judgment of the trade-off between the medium-term inflation trajectory and economic growth prospects. Unlike the single-minded technocratic pursuit of a specific inflation target using only monetary policy levers, inflation management in the age of shockflations would involve the mobilisation of monetary, fiscal, and other instruments and would require the central banks to act in concert with governments.

The political economy of inflation management centres on food, fuel, and housing prices. As climate change and geopolitical tensions rise, supply shocks on food and fuel are likely to become increasingly frequent and exogenous. When faced with inflation arising from supply shocks on those goods whose consumption is both inelastic and essential, apart from being blunt, monetary tightening can be counter-productive. In these circumstances, as much as experts will be displeased, it’ll be required to draw upon a much wider set of policy instruments - trade restrictions, buffer stocks, price controls, fiscal transfers etc. On the same lines, rent controls and minimum wages will have to be on the table to address housing affordability and wage stagnation.

There are well-known dangers associated with the use of these instruments and it’ll be a challenge to pursue them without engendering distortions and excesses. But without them, we might not stand any chance of making a meaningful dent in the inflation problem. Worse still, the political economy of food and fuel inflation will anyways end up forcing the politicians into these instruments and that too with a damaging populist tilt.

It might therefore be prudent to proactively engage with these instruments as a matter of policy. One way to limit the distortions and excesses with the use of these instruments is to lay down the principles on the triggers and boundaries for their use, how each should complement the other, and an institutional mechanism for their pursuit. Taking cue from van’t Klooster and Weber, it might be useful to have a governance framework for inflation management that clearly outlines the theories of change and channels of policy transmission, the triggers and scope of use of the different instruments, the roles of different stakeholders identified, and the institutional framework for its pursuit.

The effective coordination of all these instruments and stakeholders will be very difficult. But that should not detract from acknowledging these contributors to inflation and the need to address them. Doubling down on monetary policy levers without complementing them with the other instruments will only hurt the economy without controlling inflation.

There's a need for a vigorous public debate on this issue.

Finally, as an aside, Aswath Damodaran points out that a higher interest rate enables market discipline.

A market with a T-bond rate of 4 per cent is much healthier than a market with a T-bond rate of 1.5 per cent. People don’t feel the urge to do stupid things… the fact that the T-bond rate is 4 per cent is a good sign for the markets and for the economy. All this talk about “when will the Fed lower rates?” completely misses the point. This is where we ought to be.

I have blogged earlier questioning the wisdom of pursuing a 2% inflation target, one with limited objective and historical basis. Further, the 2% inflation target has distorted expectations by making monetary authorities implicitly pursue a lower interest rate and T-bond rate. But in the current circumstances, this pursuit of the 2% target (on inflation and interest rate) runs the risk of strangling economic growth and creating expectations that result in financial instability.

In fact, given the long struggle of central banks in developed countries to escape the zero-bound, the IMF and others have in recent times argued in favour of a higher inflation target or at least a wider inflation band. Further, the financial market distortions created by the long period of ultra-low interest rates are too well known to be reiterated. The current inflation scenario can therefore be viewed as a return to normalcy.

Therefore, instead of targeting the lowering of the prevailing T-Bond rates, the time may have come for central banks to pause on its monetary tightening and lower rates but only to a level consistent with a new higher inflation target. Instead of explicitly outlining the higher target, central banks could allow the economy to adjust gradually to the new higher inflation level and thereby restore normalcy.

No comments:

Post a Comment