Kyle Chan has a very good blog post where he discusses the landscape of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and their incentive system. This post will discuss the relevance of such models and structures in the Indian context.

Contrary to perceptions of lumbering and inefficient giants, thanks to several rounds of mergers, restructurings, and rationalisations, the larger central government SOEs are today highly profitable. Further, instead of profit maximisation, the priority of these enterprises is to serve as instruments of industrial policy and national economic priorities.

Chan points to two conflicting goals that the government faces in the management of these SOEs - harnessing the power of market competition to drive productivity and innovation as well as meet public interest goals, while also avoiding “excessive or vicious competition” that’s damaging to the industry and is unsustainable. He describes this delicate balancing as a system of “managed competition where SOEs compete for business but operate in a co-ordinated industry landscape”.

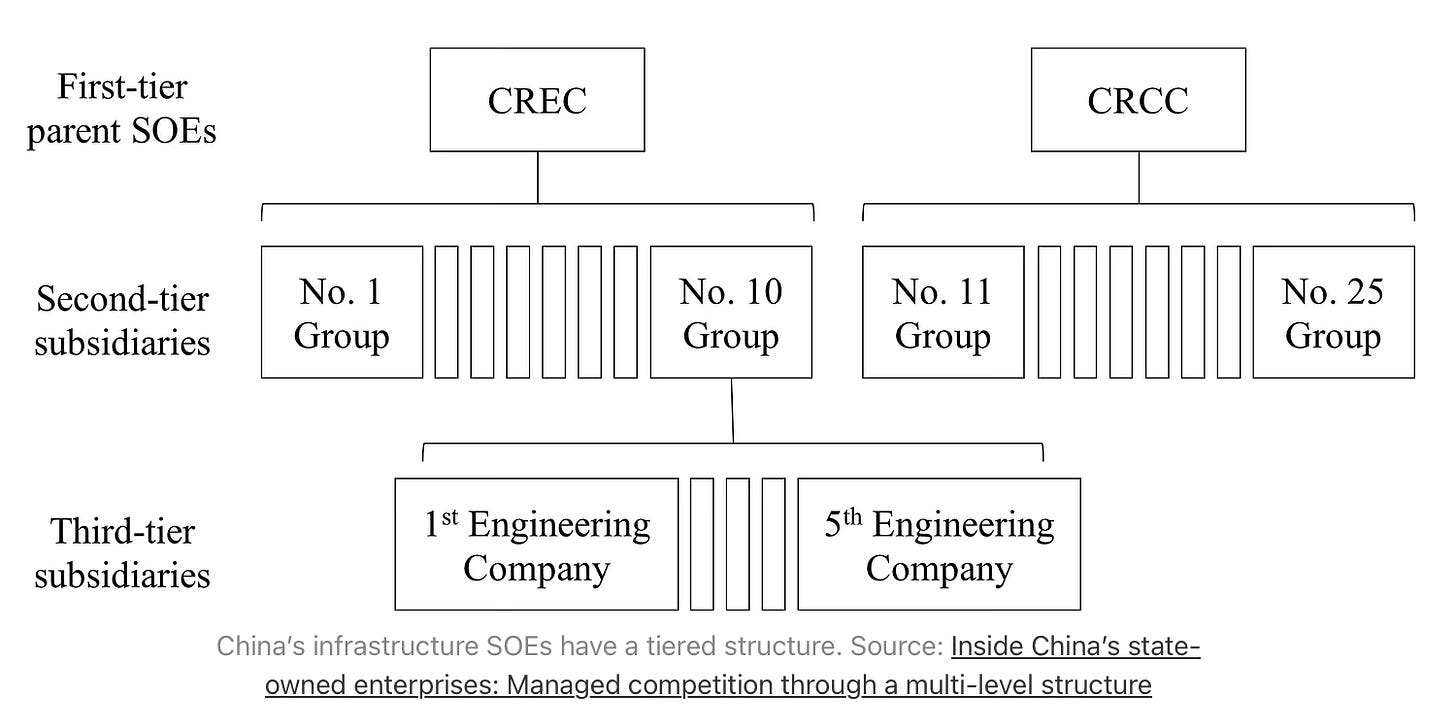

He gives the examples of two massive infrastructure construction companies, China Railway Group Limited (CREC) and China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC), which undertake railway, highway, bridges, tunnels and other construction projects within and outside the country. These are large conglomerates made up of over a dozen regionally-based subsidiaries each with similar size and capabilities.

The subsidiaries have a certain degree of autonomy and compete for construction contracts, like building a segment of a high-speed rail line in China. They bid directly on projects across the country and even around the world. Meanwhile, the two parent companies play a coordinating role, moving around resources, technology, equipment, and managerial personnel across the subsidiaries to ensure a relatively balanced set of competitors. This has been a key part of China’s success with building large-scale infrastructure. Multiple competent, well-resourced construction firms compete for contracts. If there are any issues, contractors can be swapped out relatively easily. And the parent SOEs help to maintain this balanced set of competitors, making sure that no single subsidiary gets too weak or too dominant.

The bizarre structure of these SOEs and even their oddly generic, number-based names come from their legacy as administrative units within the former Ministry of Railways bureaucracy. In the pre-reform era, these SOEs were actually regional subdivisions of the Ministry of Railways’ construction arm. Before that, they were part of the Railway Corps of the People’s Liberation Army, which is partly why they retained a closed-off industry culture for many decades. Over time through a series of reforms, they were spun out of the Ministry of Railways and turned into these two groups of infrastructure SOEs.

The power and accountability structure of these SOEs mirrors that of China’s tiered political system. The parent SOEs do not micromanage the work of the subsidiaries but instead monitor their progress on certain metrics and intervene selectively to keep the competition fairly balanced. The parent SOEs manage the promotion and career trajectories of managers in the subsidiaries. This is similar to the way that Beijing manages the promotions and transfers of provincial and local political leaders using metrics such as economic growth. CREC and CRCC themselves answer to their own “parent company,” which is the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC). SASAC is a Chinese central government body that oversees 97 of China’s most powerful and strategically important SOEs (full list here in English). SASAC itself acts like the ultimate parent company, playing a key role in appointing executives and allocating resources across the SOEs under its remit.

The Chinese experience with the consolidation of SOEs assumes significance in the context of discussions in India about merging Public Sector Units (PSUs) and creating a holding company for managing them.

The key to success here is the “managed competition” - managing the coordination among the subsidiaries within each SOE and also the competing SOEs, managing the movements of resources and personnel across the subsidiaries, managing the appointments of the executives and their promotions, managing the allocation of resources within and across the SOEs etc. Doing it in a manner that ensures productivity improvement, innovation, and competition requires considerable administrative capabilities and discipline at both the SOE and SASAC leadership levels. Besides, some such as swapping contractors and moving resources across companies can be done only in highly controlled environments.

I’m not sure about its replicability in other contexts. In countries like India where state capability and political economy discipline are scarce and with institutional restraints like the judiciary, such calibrated management of PSUs can be very difficult, even impossible.

In fact, in such contexts, there’s a strong case for dispersing power and control. For example, consider a SASAC equivalent holding company that administers all the PSUs. It would then yoke the performance of all these entities to the commitment and capabilities of SASAC. This is a high degree of risk concentration in a context where state capability is deficient, political discipline is weak, and political economy is far more complex than in China. Prudent risk diversification in turn demands disaggregation and decentralisation of control. Each PSU is perhaps best left to itself.

This example has close parallels with the ongoing problems with the two national entrance examinations conducted by the newly established National Testing Agency (NTA). While paper leakages are not uncommon, the reported manner of egregiously bad design and management of the examinations was rare even in the earlier dispersed system of medical entrance examinations.

In many ways, it can perhaps be argued that the centralisation of the conduct of the medical entrance examinations through NTA has pulled the entire system down to the NTA’s level of competence. The earlier system would have allowed for the flourishing of at least some entrance examinations with high standards and credibility.

This is also a teachable example of the perils of a centralised administrative system. It concentrates risks and pulls the entire system down to the level of competence of the central unit. Ideas like centralised procurements and centralised recruitments in general in a large and diverse country like India are not only likely to struggle but are also likely to leave the systems worse off.

No comments:

Post a Comment