Affordable housing is a very big problem across cities of the world. While there are several targeted policies to address it, including the construction of public housing, there’s enough evidence (see this), especially in the context of developed countries, to show that an increased supply of housing tends to benefit all income segments and increases housing choices for everyone.

But there are two big constraints to increasing the supply of housing - restrictive zoning regulations and neighbourhood opposition to redevelopment permissions (or the NIMBY phenomenon). The former is a problem across cities of developed and developing countries. Since zoning regulations are highly centralised in many developing countries, NIMBYism is less of a problem in their cities.

I have blogged in earlier posts in this series (here, here, here, here, here, and here) about how cities and countries across the world have been trying to address the problem of affordable housing. This post will point to an Israeli innovation that combines the easing of building regulations and local participation but with an opt-out provision to overcome NIMBYism. It’ll also discuss the successes in Texas and elsewhere due to liberalised planning regulations.

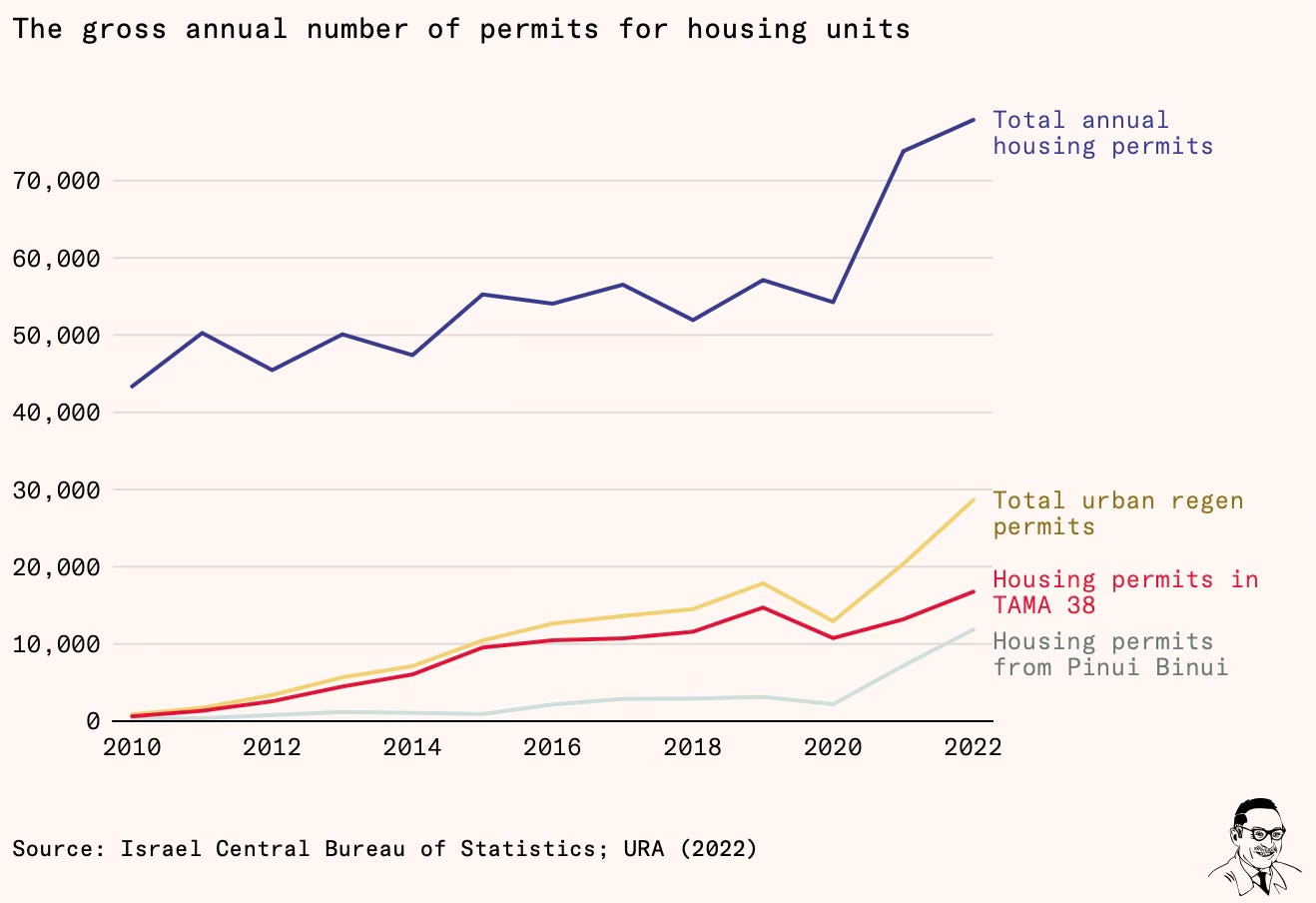

In the latest edition of Works in Progress, Tal Alster points to two housing schemes in Israel, known together as urban regeneration or UR, that have spurred densification by delivering one-third of the country's new homes and more than half of new homes in Tel Aviv. Being in earthquake zones, many Israeli homes need to be rebuilt to increase resilience. This has created opportunities for regeneration.

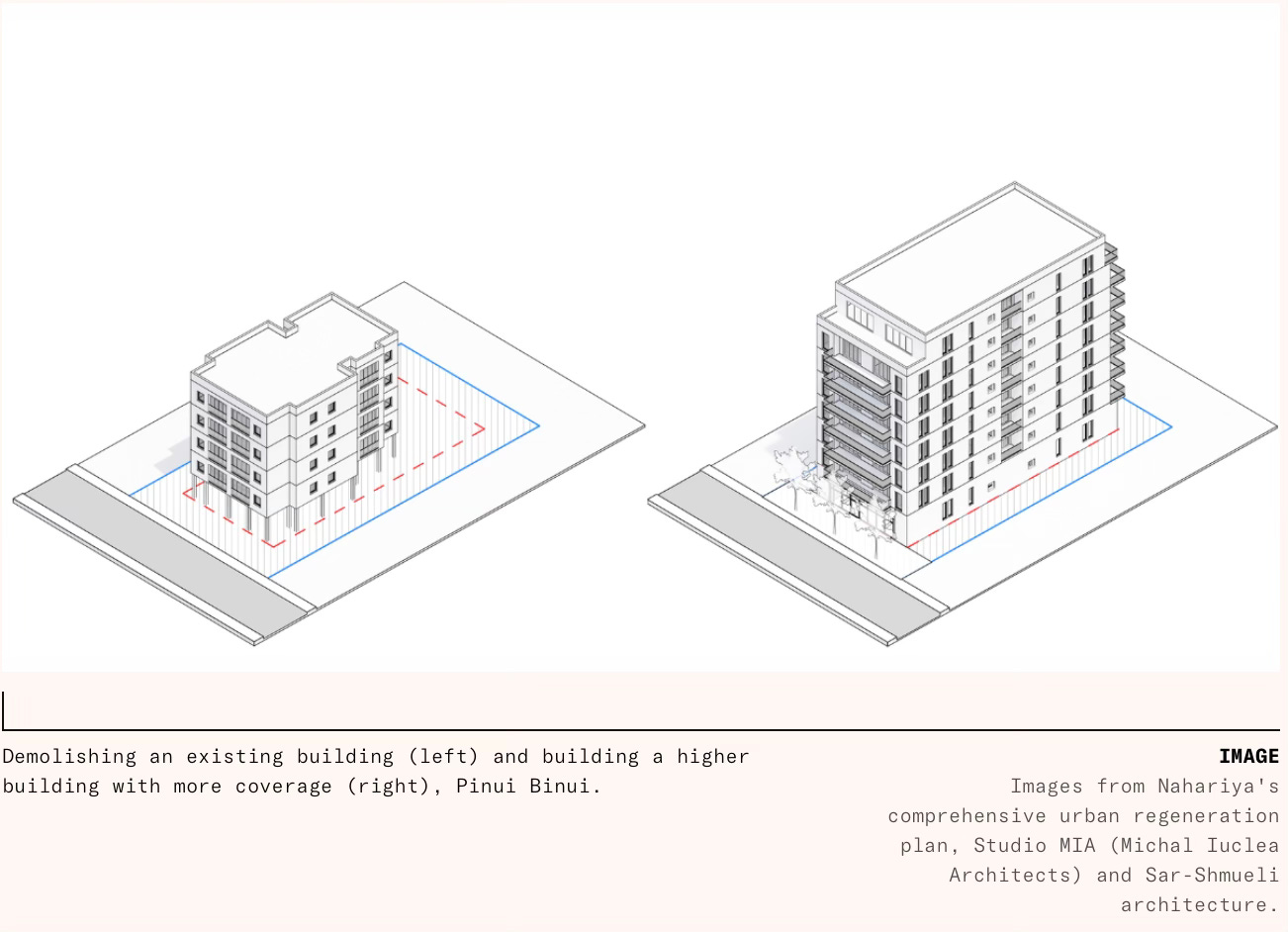

Urban planning is more centralised in Israel than in many countries and the zoning approval process is lengthy. In 1999 the government enacted a program to incentivise redevelopment of dilapidated buildings and older buildings without earthquake resilience, called Evacuate and Rebuild, or Pinui Binui in Hebrew. In 2005 it introduced a second program, TAMA 38, that allowed apartment owners in buildings built before 1980 to collectively opt to let their buildings be rebuilt with extra floors and larger land footprints, with new apartments in the building being sold to fund the redevelopment. The main objective was to reinforce earthquake resilience in older buildings. The combined impact of the two programs has been dramatic.

From just two percent in 2010, urban regeneration programs – TAMA 38 and Pinui Binui combined – now account for 37 percent of Israel’s annual housing production. The data is even stronger in high-demand areas. In the Tel Aviv district, Israel’s economic heartland, more than 50 percent of new construction is now achieved through the densification and demolition of existing housing stock. Both schemes – Pinui Binui and TAMA 38 – at heart are based on an agreement to develop between homeowners and developers. Under TAMA 38, homeowners need only make an agreement with developers; under Pinui Binui, they must also go through a zoning and planning process with the municipal, or even the regional, government.

TAMA 38, historically and currently the more productive of the two programs, offers by-right development for buildings constructed before 1980 provided the existing property owners agree, making it relevant for tens of thousands of residential buildings in Israel. There are two main versions of the scheme: TAMA addition, in which the existing building remains, but is reinforced, and extra floors are added on top, along with added floorspace on the existing floors; and TAMA demolish and rebuild, where the entire existing building is demolished and replaced by another. Developers can also propose projects through TAMA 38 that apply to several adjacent buildings, requiring consent from each, but most schemes involve single buildings. Development done through TAMA 38 usually adds three floors to each building, including one set-back top floor, normally referred to as 2.5 floors. But article 23 of the plan allows municipalities some flexibility in adjusting the limits upward or downward to meet the local context. Some municipalities allow TAMA redevelopments to add more floors, while others (mostly in high-demand areas) have limited the number below 2.5.

The scheme works mainly through property developers who contract with the landowners. The article writes about the mechanism for mobilising landowners and obtaining consent and the incentives provided.

The core mechanism in both schemes – TAMA 38 and Pinui Binui – is an agreement between a developer and the homeowners (but not renters) of one or a group of apartment buildings. In both cases, the agreement specifies the size and interior specification of the new apartments, plus what other amenities such as parking and storage space will be built, along with expected timelines and withdrawal conditions. Usually, before a developer is selected, a representative body of homeowners is elected by a general assembly of the homeowners. These representatives have the mandate to choose a developer based on criteria such as the size of the new apartments they offer, the apartments’ specifications, the developer’s experience and past developments, and its financial abilities. After a developer is selected, a legal agreement written by the developer is offered to all homeowners, who can sign it, comment on it, or refuse to sign, using their own legal advice.If two thirds of homeowners sign, the developer can proceed with the planning and permitting process. Technically, all homeowners need to sign, but the developer can sue them to force them to do so if two thirds are agreed – so long as the objectors don’t have a very strong legal case not to sign. This generally only extends to unfair deals that don’t benefit all residents, cases where the developer hasn’t provided temporary accommodation during development, or risky cases where the objectors don’t have strong enough guarantees that the developer won’t disappear or go bankrupt. The majority have a strong bargaining position, as only a narrow set of grounds are accepted for refusal, and if the court rules that the refusal to approve the deal is unreasonable, it can even force reluctant homeowners to compensate the others for delaying or preventing the deal. Initially, rules required 80 percent of homeowners to agree on a deal. Lawmakers reduced the threshold to two thirds, in order to streamline the process and lower the bargaining power of holdouts – especially those who hope to extract surplus profits from the project, on top of that available for the rest of the owners...When the agreement reaches a sufficient majority of support to be approved, then apartment owners are effectively trading their rights over their building, and the land underneath it, with a developer. Usually this is for a new, improved, and bigger apartment, often with additional amenities such as a balcony and underground parking. The developer, on the other hand, gets to sell the additional units added to the building. Regulators encourage developers to offer to enlarge the current owners’ apartments by an extra room each, or about 12–13 square meters. But this can vary enormously... Pinui Binui projects normally add as many as four or five new apartments for each existing one, meaning much bigger windfalls for homeowners, after the slower and riskier approvals process... Typically when developers or homeowners use new planning permissions they have been granted, they pay a 50 percent betterment levy on the increased value paid to the local authority, so the local community can capture some of the benefits. Under TAMA 38, owners are completely exempt from the betterment levy; under Pinui Binui it is usually set at a reduced rate of 25 percent.

The critical thing here is the role of qualified majorities which ensures that certain hardcore recalcitrant individuals cannot hold out in the hope of bargaining a higher price or for some other reason. It removes their veto and encourages developers. Such vetos can be overturned and redevelopment facilitated through two means.

Either development can be approved directly by the central government, cutting out the veto players that gum up the process locally, as New Zealand recently did in the rebuilding of Christchurch, and like the Établissement publics d’aménagement development corporations in France that built, among other things, Paris’s La Défense skyscraper-heavy financial district. The other option is to establish, at the central government level, rules that allow existing residents to overrule objectors locally and approve development directly. A similar sort of mechanism exists in most countries with so-called strata title for apartment buildings, such as Australia, Canada, Japan, and Singapore. Strata title is a legal construct that allows residents to own their own property outright, plus a share in a sort of company, which manages the building, charges fees, carries out repairs and maintenance, and more. Previously, owners in a strata corporation had to get unanimity if they wanted to dissolve it – most often because they wanted to redevelop the land. This was generally insurmountable due to holdouts, but strata owners can now usually agree by supermajority to drag along objectors, if those are small in number.

The Israeli government has adopted an iterative approach to the urban regeneration program.

Every year, the national legislation process tweaks the TAMA 38 and Pinui Binui programs in response to the needs of owners, developers, and municipal governments by shifting supermajority requirements, adjusting tax exemptions, creating compensation mechanisms for legitimate objections and for vulnerable groups such as elderly owners, and improving the rules to protect homeowners from mis-selling, fraud, and predatory pressure. The supermajorities for Pinui Binui and TAMA 38 demolish and rebuild were reduced from 80 percent to two thirds in 2021 and 2023, respectively. In 2018, in response to the unique needs and interests of elderly owners in Pinui Binui projects (that can easily last over a decade from start to finish), lawmakers amended the law to require developers to offer them alternatives to the new apartment. For owners above the age of 75, the developer must offer three choices in addition to the new apartment – to fund a stay in a senior home during the construction of the new building, to purchase an equivalent apartment instead moving to a temporary unit and then back to the new building (in order to avoid two moves), and to offer cash payment instead of a new apartment. Mis-selling has also been a problem. Less-informed and less-well-off owners sometimes agreed to unfair deals with developers... A 2017 law introduced the obligation to include timelines in agreements, and the need to inform the owners of the agreement in a meeting that includes at least 40 percent of the owners. The law also obliges developers to translate the agreement into any relevant languages.The public agencies governing the schemes have evolved too. The Urban Regeneration Authority, which began as a department in the Ministry of Construction and Housing, became an independent authority in 2016, making it less political, more professional, and more powerful. It manages the yearly legislation to streamline and improve the process, actively promotes specific Pinui Binui plans (usually in less-affluent areas), tries specifically to encourage urban regeneration in Arab and ultra-Orthodox communities (where it is currently almost nonexistent), and publishes up-to-date data on the state of urban regeneration. The Israeli Ministry of Finance, usually considered to be fiscally hawkish, nearly tripled the Urban Regeneration Authority budget between 2020 and 2022, indicating that the government believed the programs were working well. Municipal regeneration agencies, working inside the municipalities and supervised by the national Urban Regeneration Authority, were established to mediate between developers and homeowners, and are generally considered to have succeeded in getting municipal governments to be more committed to urban regeneration. Alongside these public interventions, some practices have developed incrementally via markets. For example, it is now standard for owners to hire a lawyer and a construction supervisor specializing in TAMA 38 in order to help them decide among interested developers – the developer that wins pays them a standardized fee.

Alster proposes making more changes to make UR schemes attractive for tenants and renters too.

Renters are practically invisible in the Israeli urban regeneration process, despite the fact that around a third of them have been living in their current apartment for five years or more… If Israeli policymakers want to retain the urban regeneration schemes, they should consider making them work for tenants more directly. Other options exist, such as relocation assistance for the displaced renters (available in Washington, DC, Seattle, and Chicago), or more radical steps such as a right to a home in the new project (as happens in California). Perhaps the most obvious option is to include tenants in the vote on whether to implement the project (as happens with public housing tenants in London).

This is a very strong conclusion

The data suggests that the NIMBY/YIMBY debate is not really about economic or cultural ideology, race, or class – it is about veto players and incentives. If incentives are closely tied to the decision about whether to upzone, and homeowners can make the choice for themselves, then developers can offer strong-enough incentives for new development to make homeowners the most powerful political engine in support of densification... give homeowners the right powers and incentives, and you have a good chance of delivering a lot more housing – with the enthusiastic support of locals.

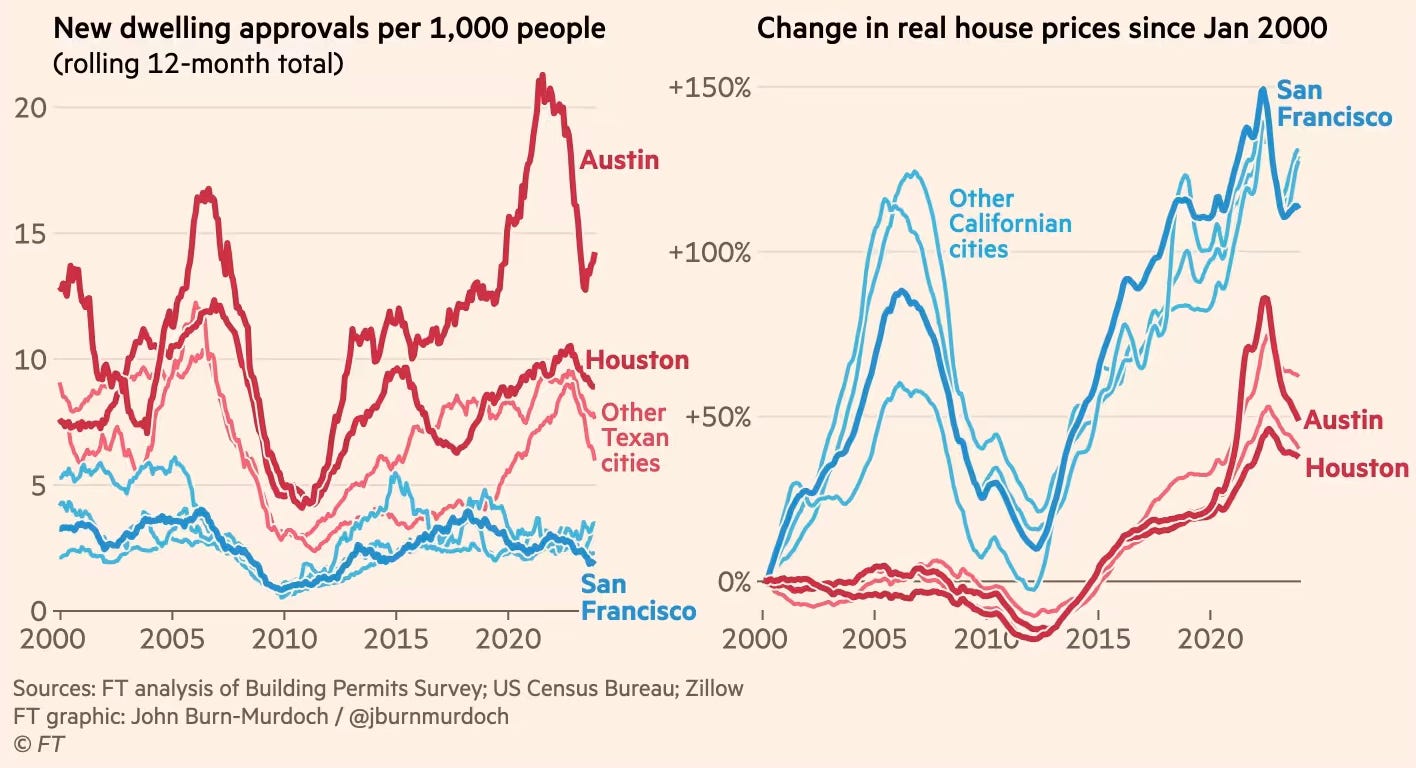

John Burn-Murdoch in FT has a brilliant article where he points to the success of Texas in keeping housing prices affordable through increased supply from liberalised planning regulations.

In the year ending March 2023, construction began on 72,000 new homes in Houston, Texas, population 7.5mn: more than three times the 20,500 new homes started in London, whose population is considerably larger… Swap Houston for Austin, and London for San Francisco or New York, and the disparity would be even larger. Unsurprisingly, these wildly divergent rates of housebuilding have an impact on prices. You would have to pay $1.2mn dollars for the average property on sale in the San Francisco/Oakland area today, around $800,000 for the typical homes in London and New York, but just $300,000 in Houston.

The disparities only become more striking if you consider the local context. New York, San Francisco and London are led by progressives who wring their hands publicly over their acute and long-running housing crises. Texas, meanwhile, is a red state, not generally given to pursuing socially beneficial projects. But actions speak louder than words. Homes in Texan cities are cheap and their populations soaring because the state has made urban development easy. California, New York and London are overheating and squeezing out young families because their planning systems place artificial constraints on supply, making urban development extremely difficult.

Burn-Murdoch points to how cities like Houston and Auckland have overcome local opposition with creative opt-outs and focusing on smaller developments.

In Houston, a 1998 change to planning laws empowered landowners to turn one home into three — instantly creating space for new families in the heart of the city, while generating a tidy profit for themselves. A crucial detail was the inclusion of an opt-out for individual neighbourhoods whose residents wished to keep things as they were, increasing the scheme’s durability. Auckland’s 2016 upzoning plan worked in a similar way, creating new defaults that facilitate modest densification in areas close to the city centre and transit stations while keeping carve-outs for neighbourhoods of historical significance. In both cities, construction has soared and prices stayed much lower than elsewhere. Crucially, by focusing on what urbanists call “gentle density” — involving developments of anywhere from three to six storeys, designed with local character in mind — and building in exceptions, both plans have endured political upheaval.

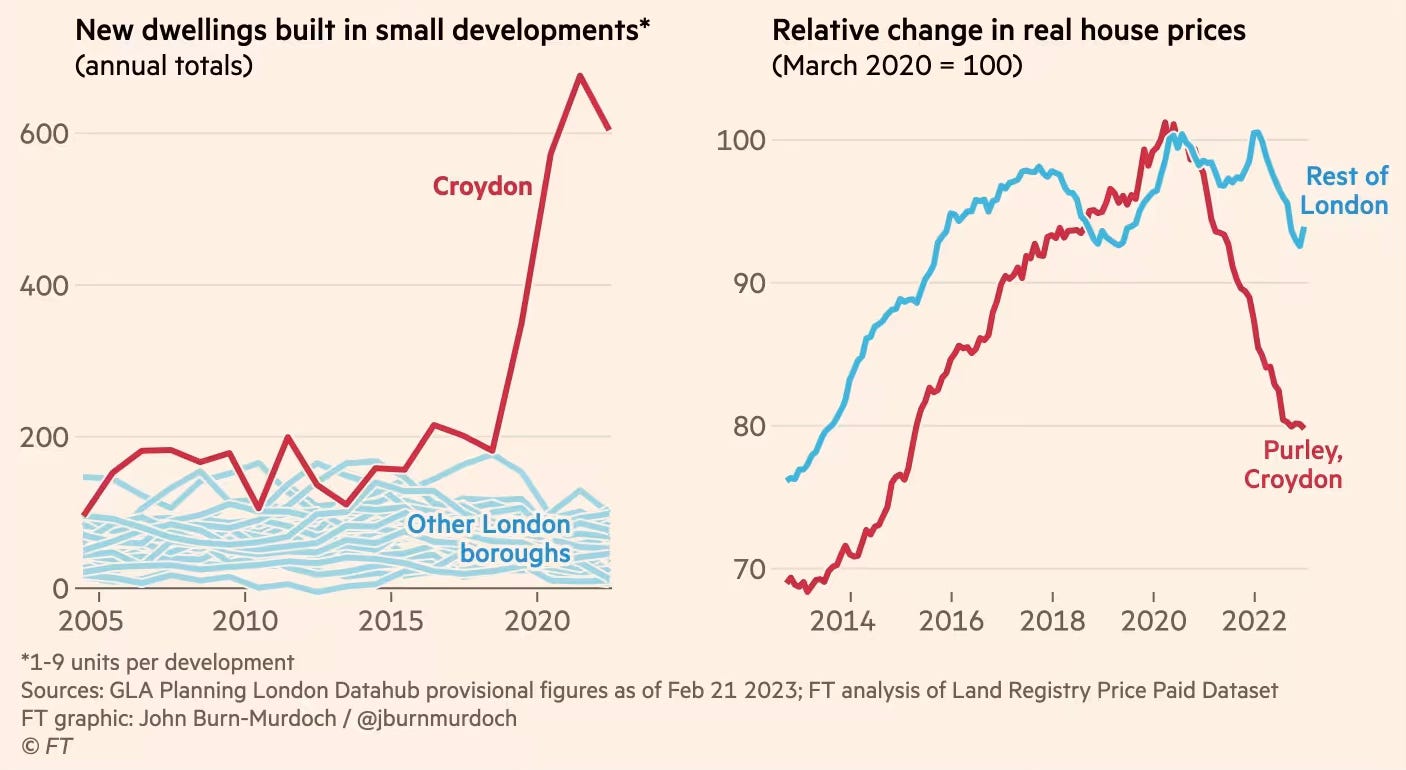

He also points to the success of London suburb Croydon’s brief experiment which allowed homeowners to convert large homes into multiple apartments, that increased supply and lowered prices.

In 2018, the borough of Croydon published new planning guidance allowing homeowners to redevelop their large single-family homes into medium-rise apartment buildings containing multiple units, provided the new designs were broadly in keeping with the form and building materials of the local area. The policy applied to the whole borough, with no carve-outs. The number of these small developments rocketed, adding hundreds of new apartments selling at prices far below the previous norm. Both supply and affordability improved dramatically almost overnight. But it didn’t last. The new policy became a key focus for anti-development campaigners in a fiercely fought mayoral election, and the borough’s new Conservative mayor repealed it just four years after it was announced. With that, the small densification projects came to an abrupt halt.

Some observations with relevance to the Indian context:

1. The Isreali example is very relevant for India. Mere incentivisation by way of higher FAR or lower building fees will not be sufficient to encourage landowners to redevelop in significant numbers. There’s also the need to overcome the financing (the financing required to redevelop) and co-ordination (to mobilise owners in a multi-tenament unit or bring together adjacent lands) problems. Policies that facilitate builders and developers address this problem is the crucial innovation in Israel.

The success of such policies depend on how attractive it is to both the landowners and builders. The former should be able to get a larger and higher-valued property without being significantly inconvenienced during the transition. The latter should find the deal commercially attractive - they get enough additional units to make up for the units foregone to landowners and get a handsome profit. The credibility of this scheme will depend on whether the landlords generally abide by the provisions of the contract and deliver the houses at good quality and within the stipulated timelines.

This can be a challenge given the widespread presence of unscrupulous practices in the real estate sector in the country. It’s therefore important that any such scheme and registered developments be tightly regulated.

2. The Israeli example also highlights the importance of iteration with complex policies like TAMA 38 and Pinui Binui. There will be several emergent problems once the first version of the scheme is announced, necessitating several iterations before the scheme stabilises. One of the big problems likely in the Indian context would be concerning the possible exploitation of landowners by unscrupulous builders in connivance with the local politicians and officials. Therefore the use of qualified majorities will have to be phased in very carefully.

3. Another problem with such renewal is the strong likelihood of displacement of the existing lower-income owners and the resultant gentrification. The redeveloped units will be bigger and better, and have maintenance costs. They will also fetch a much higher market price. The owners are therefore likely to find it attractive to sell the redeveloped property to higher-income households. The longer-term consequence of such gentrification is that even blighted and older areas of a city become out of bounds for all but the well-off households. The city becomes less inclusive. Such policies will therefore have to address this problem by iterative evolution.

4. As I have blogged here, I’m not convinced that easing regulations alone will be sufficient to increase affordability in any meaningful manner. The reason is that the relationship between eased regulations, supply, and affordability is far from linear. For one, the easing has to be very significant (especially in terms of much higher FAR) to trigger meaningful increases in supply. There’s also the possibility that the eased regulations and increased supply will end up being consumed by the pent-up demand from the well-off households without triggering any cascade of displacement of demand that would transmit the supply across all income groups.

No comments:

Post a Comment