Dani Rodrik and Joseph Stiglitz have a paper that discusses the economic growth strategies available for developing countries today in light of the ongoing political and technological changes.

Strategies that worked well in the past are unlikely to do so in the decades ahead. In particular, the manufacturing- and export-based growth strategies that drove East Asia’s development miracles are no longer suited for today’s low-income countries; at the very least, they are insufficient. New technologies, the climate challenge, and the reconfiguration of globalization require a new approach for development emphasizing two critical areas: the green transition and labor-absorbing services. Unfortunately, policy makers do not have ready-made recipes or successful models to emulate. Confronting this challenge head-on will require therefore also building greater capacity to learn about new opportunities, constraints, and what works and doesn’t as governments experiment with new policies on a number of fronts.

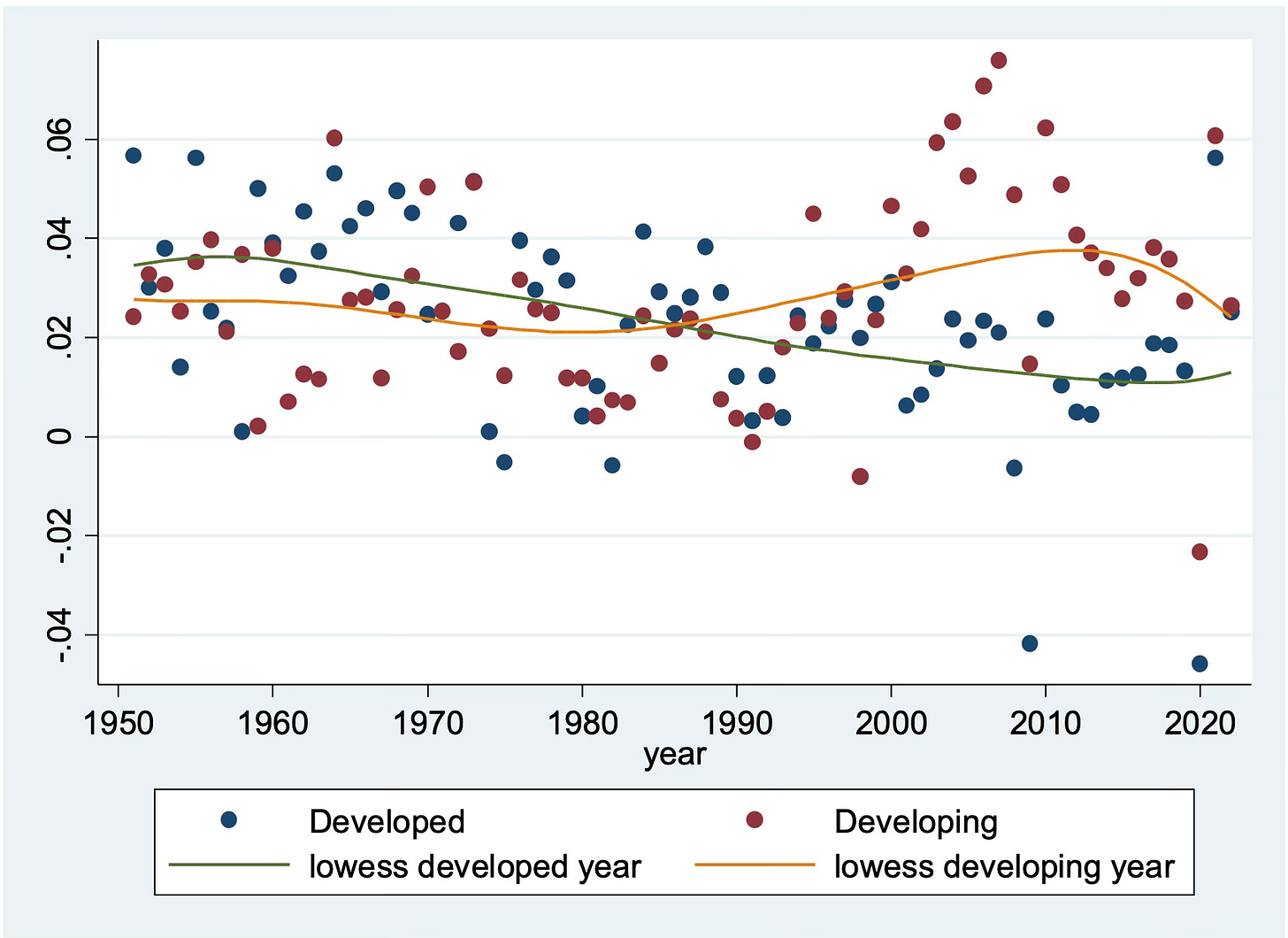

They show that economic growth rates for developing countries have been declining since 2010, necessitating the need for a new strategy.

They highlight the importance of structural transformation realised by the promotion of new and modern economic activities through the pursuit of industrial policies.

Structural transformation is the key dynamic that drives rapid economic growth. As workers move from low- to higher-productivity sectors, they increase their earnings, aggregate productivity rises, and economic growth takes place. The key strategic question that needs to be answered to launch this process is: where will the better, more productive jobs come from? While manufacturing will remain an important sector for most countries, we do not believe it can be the protagonist of economic growth in the way it was in East Asia and other successful economies of the past.

The East Asian economies achieved structural transformation by explicitly pursuing trade and industrial policies focused on export-oriented industrialisation (EOI). But this strategy now appears to have run its course on the face of skill- and capital-biased technological shifts in manufacturing. This has been exacerbated by the high quality and technological standards set by leading firms in global value chains (GVCs) that have rendered labor-intensive production in export-oriented sectors unviable. A trend of premature de-industrialisation has taken hold. The combination of all these eroded the comparative advantage of developing countries arising from their abundance of less-skilled labour. At the same time, absorption of the incremental labour supply into agriculture too is constricted given the labour saving nature of agriculture technologies and labour reducing impact of increases in agricultural productivity.

They also feel that “it is unlikely that decarbonization-led structural transformation on will produce on its own the jobs which would have been created in the past by industrialization”. While the authors see climate change challenge as “a growth opportunity if developing countries are able to turn it into an investment strategy”, they also recognise the problem of mobilising the large upfront investment requirements to pursue this strategy. It’s also a problem that many green technologies are both more capital-intensive and less labour-intensive. The authors have little to say by way of suggestions to meet the financing requirement to pursue this growth opportunity.

In the circumstances, they see services as “the main labor absorbing sector of the economy in developing countries”. Here they acknowledge that the skill-intensive IT and BPO sectors have limited potential to “create large numbers of employment for the typically low-educated, low-skilled workforce of a developing economy”. Instead their proposal of industrial policy goes along these lines,

Today jobs are largely being created in a very different segment of the economy - a hodge-podge of largely self-proprietorships or micro/small firms, typically non-tradable and often informal. The central questionon is: how can productivity and demand be increased in these labor-absorbing service activities? We propose a three-pronged strategy for governments. First, encourage lower-skill job creation by the larger firms that operate in non-tradable services. Second, provide public inputs and access to productivity-enhancing investments for smaller enterprises. Third, invest in technologies that complement rather than replace low-skill workers in service sectors.

We recognize that the bulk of small, informal enterprises in developing countries will never become very productive. It would not be realistic to aim for productivity increases across the board for all these firms. The best that can be hoped is that dualism can be reduced over time both by encouraging the expansion of existing formal firms, and by increasing productivity among some of the more dynamic smaller, informal firms. Therefore, a strategy targeting the domestic service sector must be necessarily selective. The general idea here is one of self-selection. The government would engage in a variety of programs that have the potential of simultaneously increasing employment and productivity. It would then let the more entrepreneurial and dynamic among service-sector firms, including micro- and small enterprises, to select into and take advantage of these programs.

… local governments will be often better placed than national governments to create jobs-centered partnerships with entrepreneurs or firms providing services. Given the multitude of service activities, variation in local circumstances, and the heterogeneity in the size and shape of firms, local governments may also be better positioned to craft suitable arrangements. In either case, though, significant experimentation with different types of initiatives will be needed, given the dearth of successful precedents to emulate… governments in developing countries, both local and national, will have to become more entrepreneurial and more engaged with experimentation as well, and focus on bringing innovation insights to small enterprises, if the strategy is to make a significant difference beyond individual initiatives.

They point to the importance of government action to realise structural transformation,

In general, structural transformation is impeded by credit and risk market failures, coordination failures, externalities, and learning spillovers. That is why the most rapidly growing economies of the past all relied heavily on industrial policies promoting productive diversification and the growth of new industries. Such barriers are, if anything, even greater in the transition to green industries and productive, labor-absorbing services. Hence private markets and entrepreneurship will need to be augmented by a public vision and a supporting set of public incentives, inputs, and services.

About industrial policy, the paper writes,

The practice of industrial policy has five key inter-connected elements: embeddedness, coordination, monitoring, conditionality, and institutional development. The first of these refers to the establishment of a strategic dialog and collaboration with firms to elucidate the information on obstacles and opportunities for productive investments, including market failures… government agencies charged with industrial policies need the ability to coordinate and mobilize… Third, government learning has to be systematised and reflected in subsequent actions and decisions. This requires an explicit effort to monitor and evaluate the outcomes of industrial policy decisions. Many of these decisions will inevitably lead to sub-optimal outcomes and mistakes. What maters for the success of industrial policies is not the ability to “pick winners,” (or even identify projects with large externalities) but the ability to “let the losers go,” a less difficult but still demanding requirement… Fourth, and relatedly, successful industrial policies have typically provided strong incentives for compliance. In East Asia, the financial support was not a gift; continued support required continued success on the part of the firm, often with objective indicators, like exports… Fifth, successful industrial policies require new institutions and institutional development. In many countries, development banks played an important role.

The authors give some examples of services where active engagement by the government helped expand lower-skilled jobs. They also point to theoretical examples of how AI can help lower-skilled workers overcome their knowledge and skills-deficit. But this would require very active public policy engagement, industrial policy for the services sector. The market dynamics, left to itself, will not only not be able to absorb such workers but is more likely to end up destroying or constricting the supply of jobs suited for the lower-skilled workers. But even with government intervention, I’m not sure whether such jobs can absorb the lower-skilled workers at the scale required, atleast for the foreseeable future.

I can think of some services sectors with large and increasing demand for labour - education, healthcare, restaurants and hospitality, leisure and entertainment, tourism, construction, transportation, urban services (housemaids, drivers, security guards etc), essential services like haircuts, maintenance and repairs, retail trade etc. But in all these non-tradeable service sectors, there’s a strong dualism between a higher productivity formal sector and a low-productivity informal sector. In developing countries, the latter overwhelmingly predominates the sector.

But this productivity duality exists for a reason. The higher productivity formal sector comes with a higher priced service, which the vast majority of the population cannot yet afford. There’s therefore a structural binding constraint to the expansion of this formal sector. This formal sector can expand only at the rate of growth of the population which can afford this service. This is a problem since the nature of growth of many developing countries today is lop-sided. It’s not broad-based enough to rapidly expand the population group that can afford formal sector non-tradeable services.

I have discussed this problem with the simple illustration of haircuts. How many Indians can afford Rs 100 haircuts (possibly the lowest formal sector haircut)? My guess would be a small proportion. Say 10-15%? How fast is this consumption category expanding? Is it expanding fast enough to rapidly expand the supply of Rs 100 haircuts? I don’t think so, nor do I see the prospects of this expansion promising enough.

Non-tradeable services therefore comes with a disadvantage compared to tradeable manufacturing. While the latter had the benefit of the global market, the former is constrained by the size of the domestic market. Unlike Make in India for the world, Make for India comes with its productivity drag, whether it’s goods or services.

It’s for this reason that manufacturing will have to remain the main driver of productivity growth and structural transformation, with services playing an important but secondary role. In this context, the example of Tamil Nadu discussed in two recent articles (here and here) is instructive. Investments in contract manufacturing is creating direct and indirect employment at a scale that’s required to meet the growing labour supply. But that’s only Tamil Nadu, which also had the legacy of having India’s strongest manufacturing base. What about the other states?

No comments:

Post a Comment