I’m a strong believer in the argument that there are no grand narratives or explanations for most intractable social, political, and economic problems in the world. Neither are there similarly all-encompassing solutions for these problems. Almost always, the explanations and solutions are mani-fold and often vary widely across contexts for the same problem.

Importantly, most often the solutions are about persistent and long-drawn efforts, more like hundred small steps than two or three big bang measures. These small steps create the conditions for change in culture, norms, attitudes, behaviours and practices. The challenge is to bring these steps together in a Big Push, with collective commitment and execution diligence.

On the same lines, I think that the answer to India’s economic development lies in a carefully tailored heterogeneous and varied basket of measures. There are no universal and time invariant one-size-fits-all big bang measures. Instead there should be different bouquets of measures for different localities and regions, depending on history, culture, remoteness, backwardness, caste and (even) religion. These bouquets would vary in their prioritisations and thrust on some specific set of measures aimed at the specific context.

But these measures have to be supported with a set of uniform interventions - infrastructure (mainly irrigation, roads, electricity, and drinking water), public goods (public health, schools and hospitals), human resources development (nutrition, learning proficiency etc.,), livelihoods (skilling, industrial clusters, parks etc.,), policy enablers (simplify regulations on land and labour, facilitate access to credit, ease of doing business), and good governance.

Hitherto the focus has been on a few uniformly applicable set of interventions that are mostly in the nature of brick-and-mortar infrastructure and logistics development and ease of doing business. We need to go beyond this. These measures by themselves are unlikely to address the chronic and entrenched constraints that entrap localities and regions in backwardness and under-development.

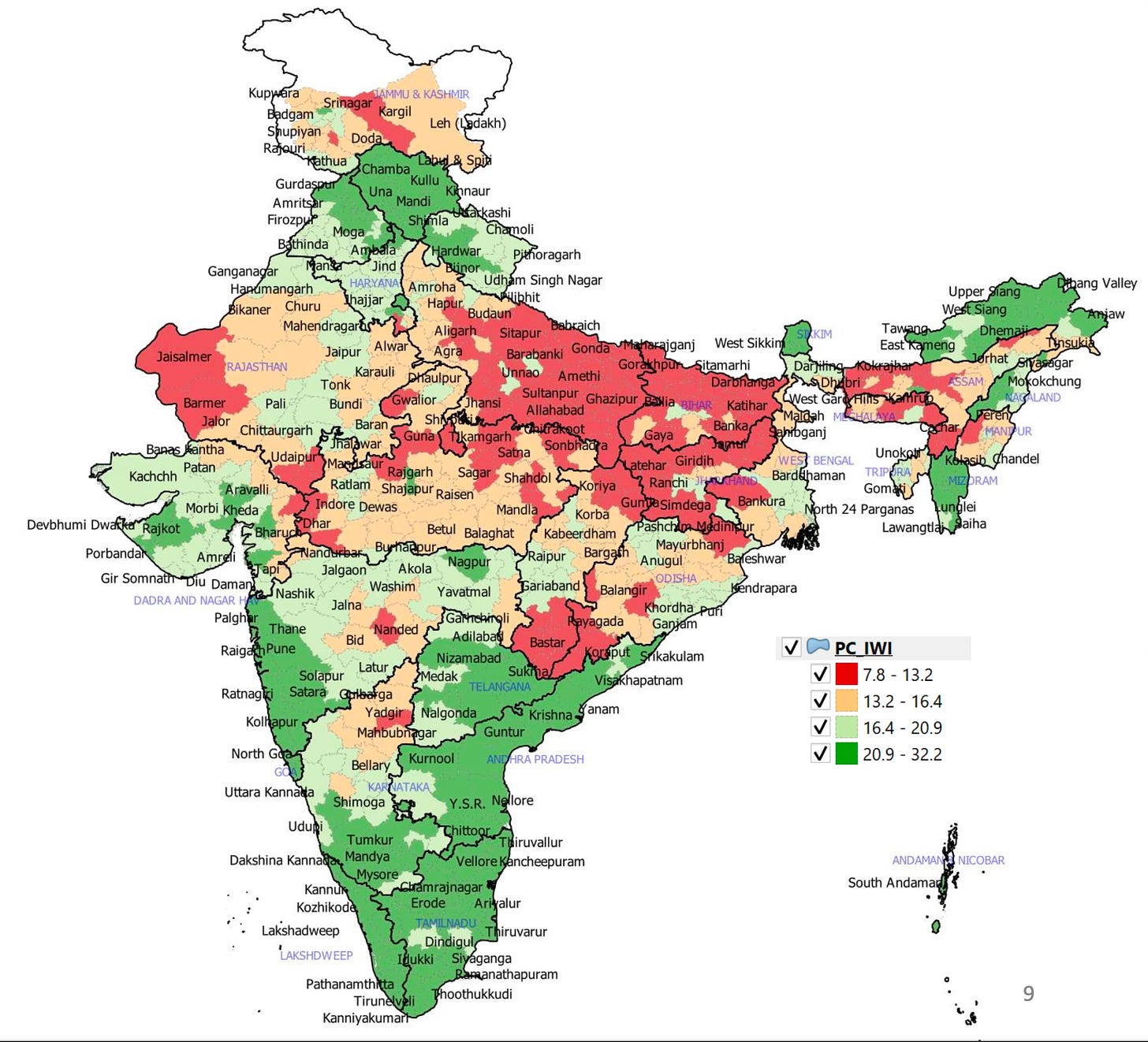

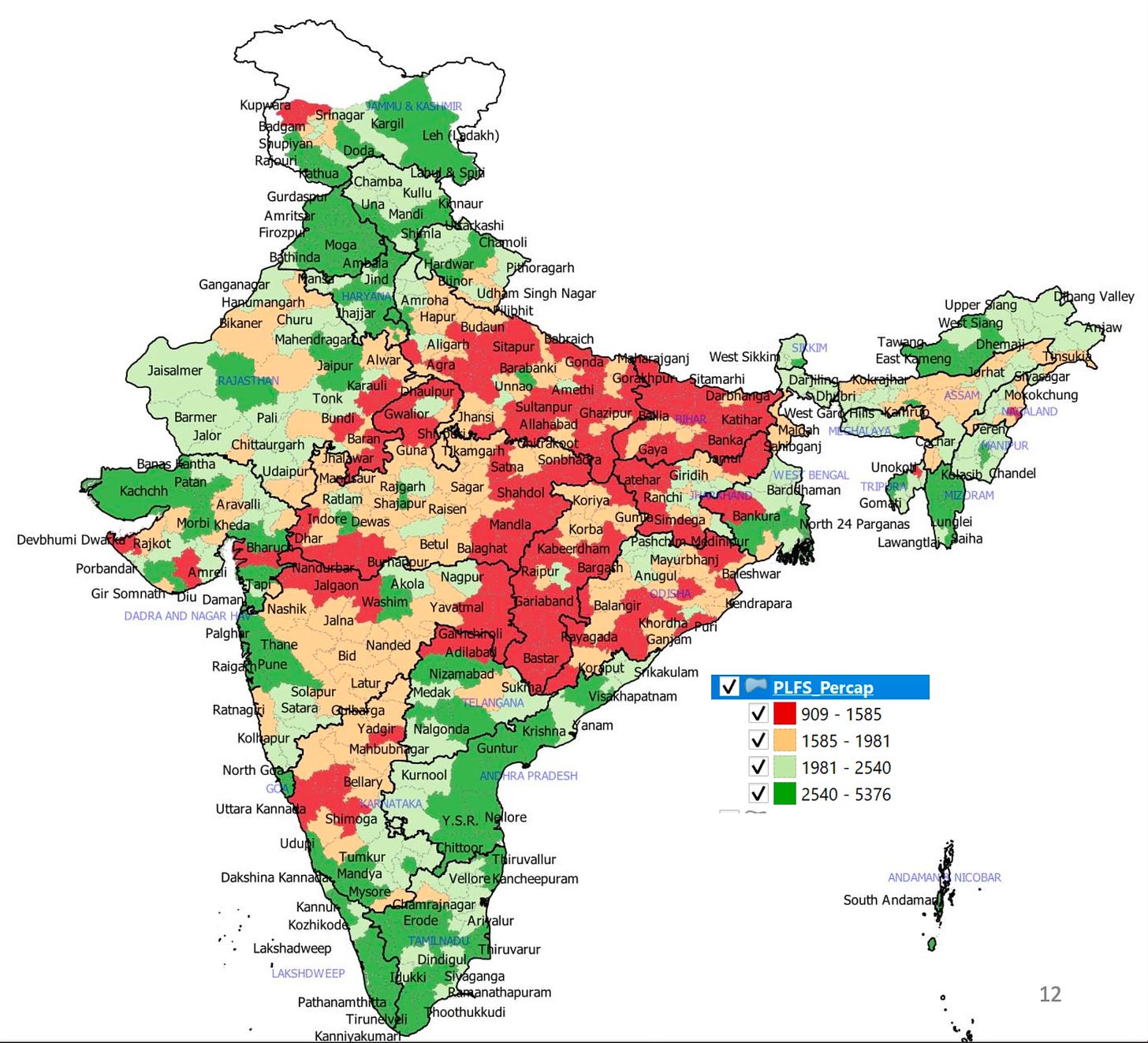

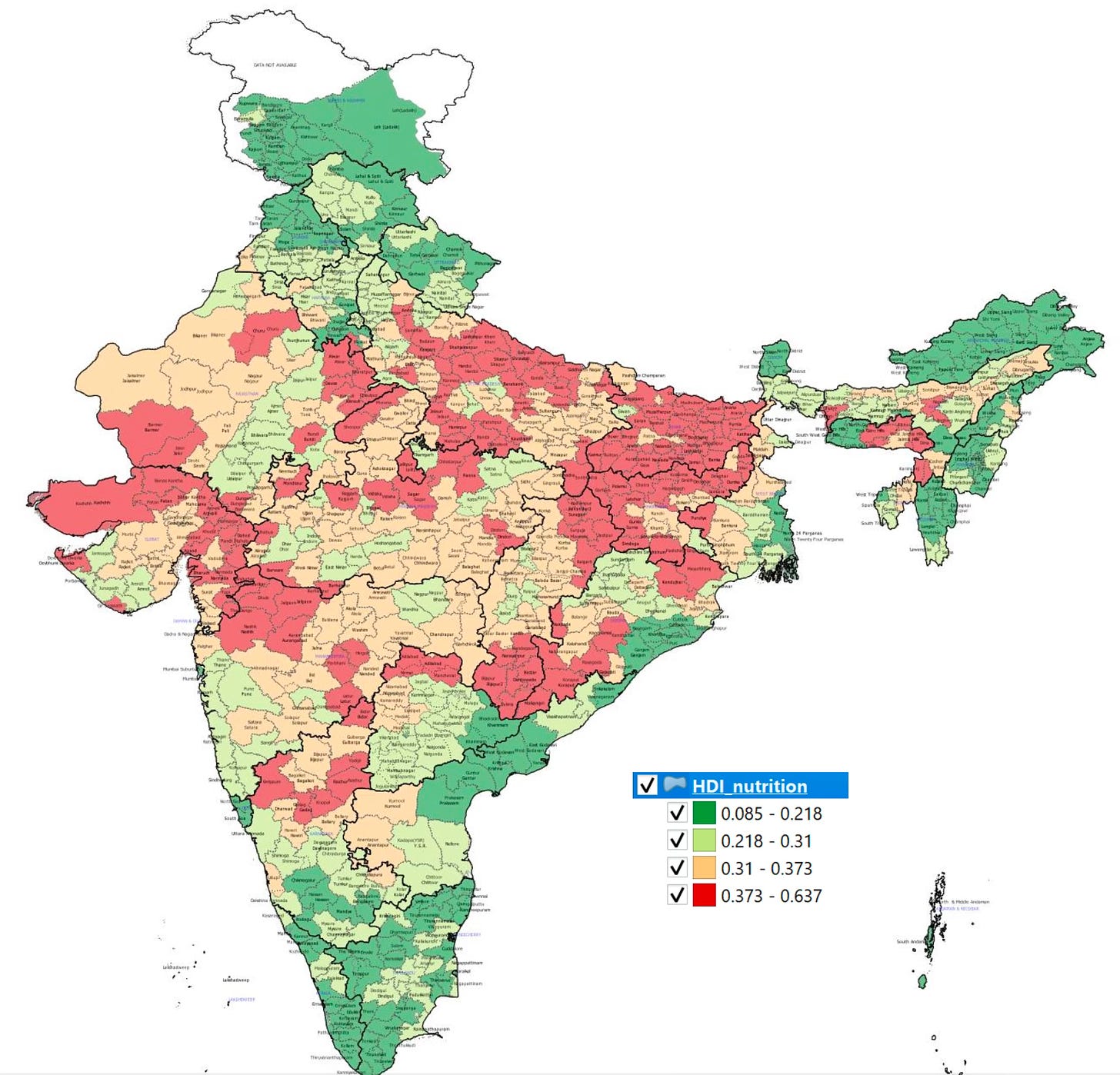

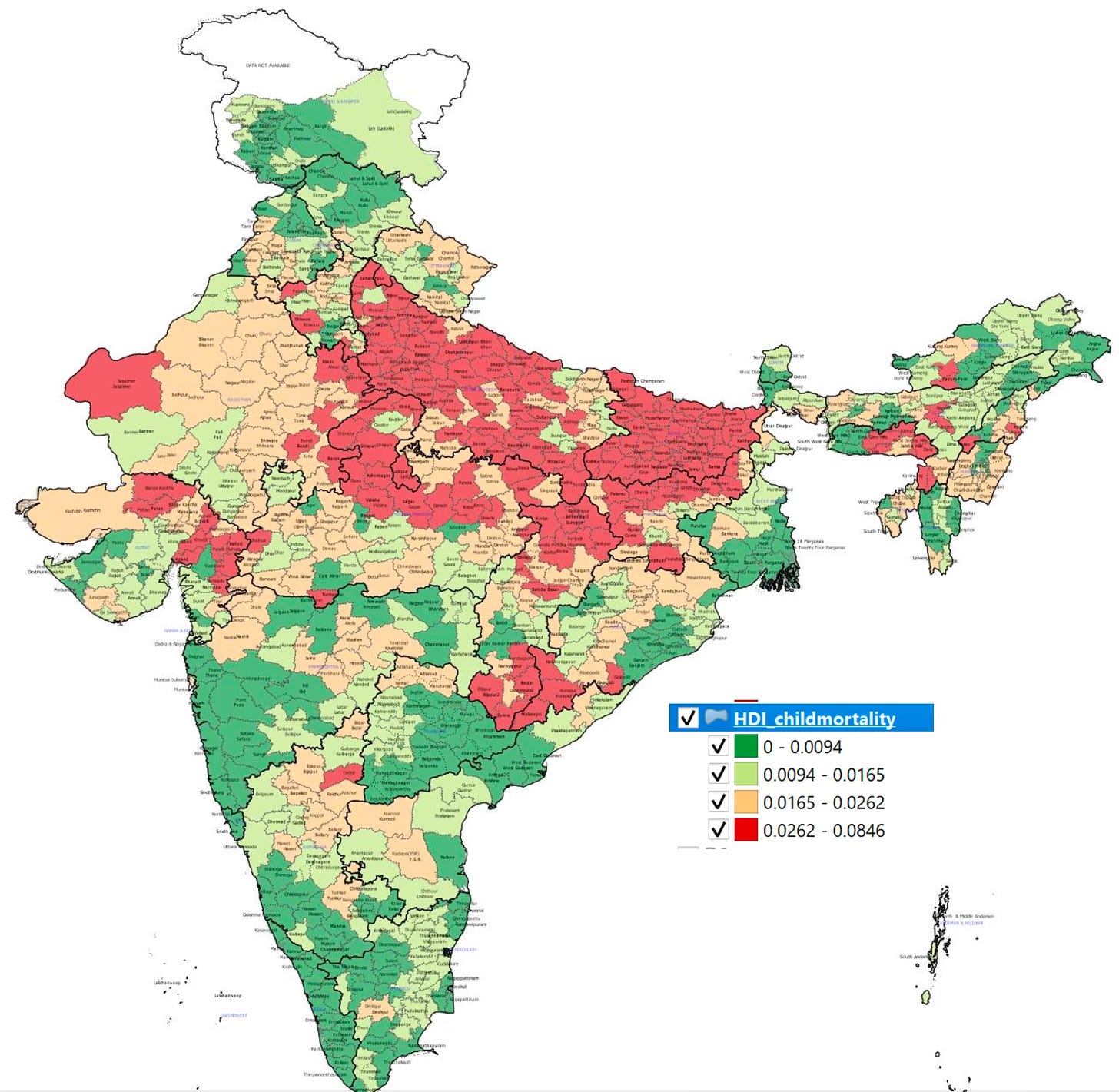

In this context, I recently came across an eye-opening presentation by Dr Sekhar Bonu, previously Director General of the Directorate of Monitoring and Evaluation, NITI Aayog. He has graciously allowed me to blog on it. In the unpublished work, he uses the existing survey data from NFHS, PLFS, and other sources to document the wide geographical variations across a host of economic and human development parameters. He uses GIS maps involving districts to illustrate the wide variations across geographies (even adjacent districts) to show why it’s futile to think of one India when we design policies to address development deficiencies. In fact, for sustainable and meaningful efforts, aside from the aforementioned common interventions, we should be thinking in terms of districts as the unit of iteration.

In another recent paper published in the EPW, Anirudh Krishna and Sekhar Bonu mapped out similar significant inter-district variations and clustering of lagging districts by intergenerational changes in education.

I’ll sample a few from the as-yet unpublished work, with his permission. He uses wealth, consumption, and human development data to highlight the differences across districts.

Household wealth index shows that poorer households reside largely in the Eastern part of North India, North East India, and East India. But per capita household wealth, a more accurate representation of wealth, show the desert districts of Rajasthan with higher backwardness, while North East districts show less backwardness.

Percapita consumption map shows North East and Rajasthan have relatively higher household monthly expenditure compared to household wealth standing, whereas pockets of low expenditures can be seen in Telangana, Karnataka, Maharashtra, TN, and Gujarat.

On nutrition while there is significant overlap with wealth and consumption expenditure, districts in AP, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Karnataka are unique to Nutritional backwardness

On child mortality, while there’s significant overlap with wealth and consumption, some districts in Karnataka and Gujarat are unique to child mortality

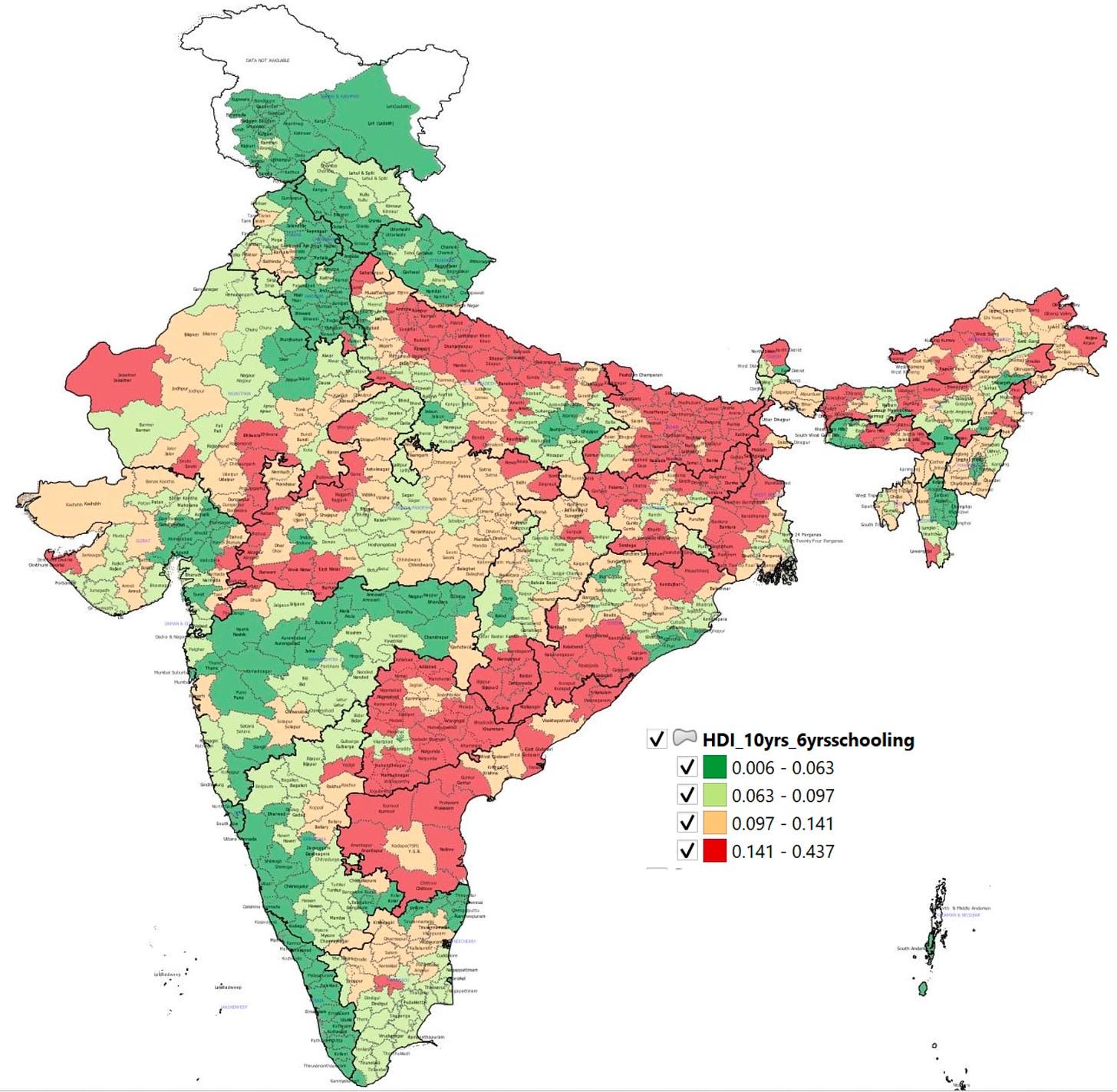

On years of schooling (where not even one member of the household aged 10 years or older has completed six years of schooling), Andhra and Telangana in particular are uniquely backward.

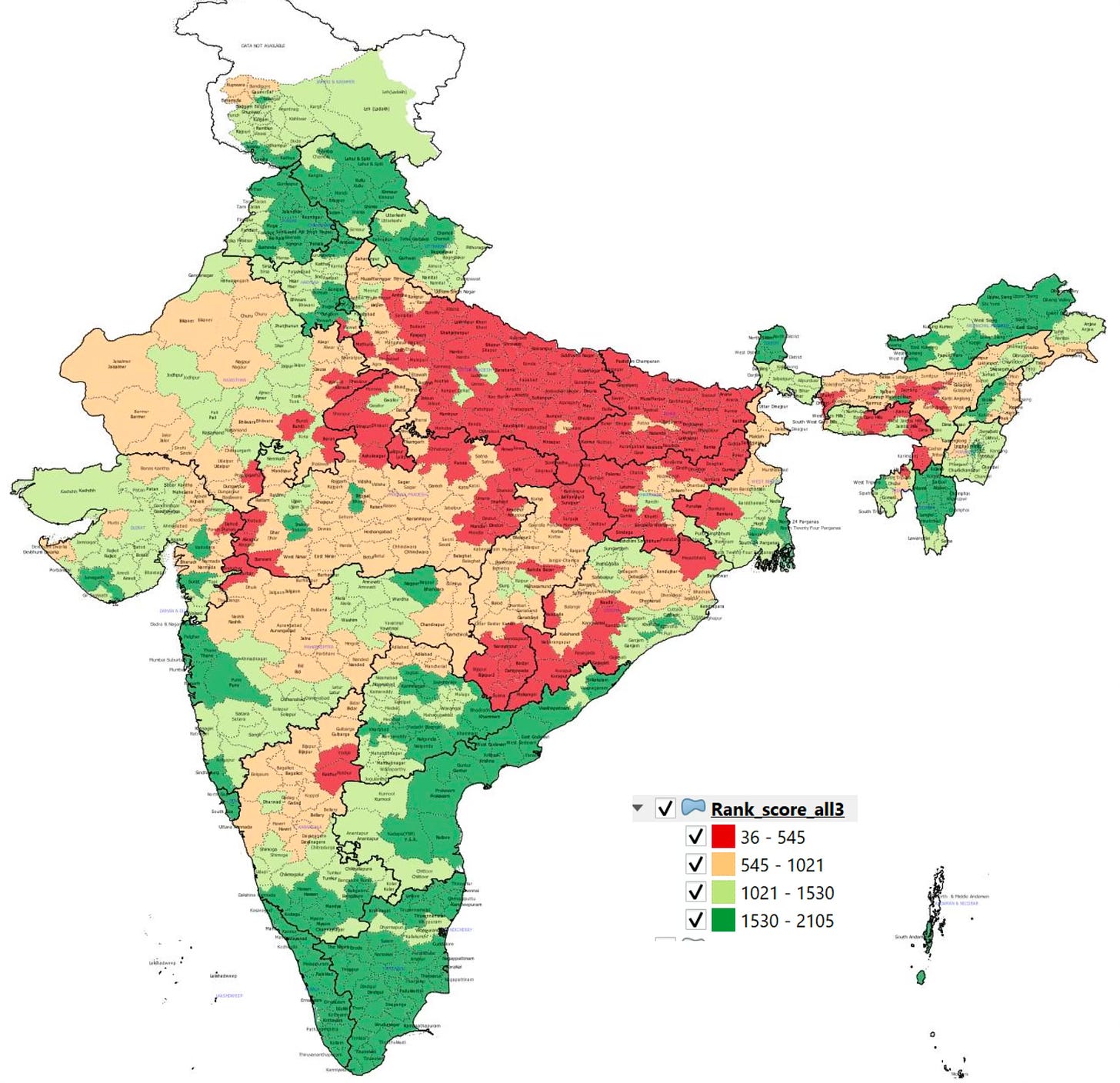

Bringing all together, he does a composite scoring of all districts based on the three kinds of parameters. Almost all districts in Bihar, large parts of UP, tribal belts of Orissa, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand, tribal cluster covering Gujarat/Rajasthan/MP and Maharashtra, a pocket in Karnataka emerge as the areas requiring support.

While the maps show several instances of districts as islands of underdevelopment, it also finds that backward districts are contiguous and clustered. It therefore advocates cluster and state-based approach over and above district-based approach to deal with extreme backwardness. It points to geographical factors of vulnerability - floods, forest, dry lands, remoteness - and historical/cultural factors among tribes, scheduled castes, and minorities.

Some general observations:

1. The maps convey a world of wide variations across districts within the same state, underlining the point that there’s no one India nor even one state when it comes to human development and economic growth. At best, there are geographical clusters.

2. If we take all these maps together, it’s clear that in terms of states, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh are where India’s biggest human development and economic growth challenges lie. Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and South Karnataka stand out, followed some distance behind by west India including North Karnataka. Maharashtra and Karnataka pose a problem given the co-existence of prosperity and development with backwardness and underdevelopment.

3. This also means that reconciling these variations with practical administrative convenience, we can perhaps have four or five broad categories of national programs on education, health, nutrition, skilling, drinking water, irrigation, housing, rural electrification, social welfare etc. One for the core southern states; another for Punjab, Haryana, HP, J&K, and Delhi; one for the west; another for the northern states; and a fifth for North East. Perhaps the first and second could be merged. Maybe we start with just three. This could be a prudent first step in reforming the current one-size-fits-all approach of central share and central sector programs.

4. The clusters and contiguous districts can perhaps be significantly be addressed through Big Push measures, primarily focused on irrigation, connectivity, and electricity. But this alone will not be sufficient. It’ll also require some economic growth catalysis. This part is difficult. For example, these clusters could benefit from some growth anchor or igniter - a town/city within the region, an industrial cluster/corridor, a large new investment, a large government institution etc.

The isolated district (or 2-3 districts) are a much bigger problem. They are entrapped in bad historical equilibriums and would require more concerted district-wise efforts to relax cultural, historical, caste/religious constraints.

5. I’m not sure about the mechanics of implementation of the second layer of context-specific interventions. For simplicity, I can only say that these interventions will need to be carefully thought out by involving stakeholders, prioritised, and a 20 year plan made with clear outcome objectives and intermediate milestones and timelines. This will include prioritisation of infrastructure investments, economic growth interventions, and measures to relax the social-cultural constraints. As a note of caution, the danger here is that this exercise will get outsourced to some management consultant, thereby signifying a kiss-of-death even before the implementation has started. This effort will be blunt without an explicit acknowledgement of state capability weakness and poor governance, and efforts to address them.

6. I can think of two areas to build on this work. One, change in these economic and human development parameters over time based on investments in roads (PMGSY), irrigation (PMKSY and projects coverage) and electricity, and programs like NREGS, Poshan Abhiyan etc. Apart from being an evaluation of these flagship programs, it would also throw up insights on whether these alone are creating any impact and whether there’s the need for complementary interventions.

The second is to introduce elements of state capability and governance. I’m inclined to believe that whatever one does with hard infrastructure and public goods, and enablers, without good governance it’ll be hard, if not impossible, to break out of entrenched backwardness and poverty. What are good indicators of governance? I can think of comparisons on vacancy of teachers, nurses, and doctors in primary schools and primary health facilities; average expenditure percentages of certain important programs (or program components); some measure of institutional penetration (Police Station, Post Office etc per unit of population or area). For sure, there’ll be endogeneity in many of these with backwardness.

No comments:

Post a Comment