This blog has long highlighted the importance of narratives in shaping beliefs, cultures and policies. And such narratives often stand in stark contrast to the realities of the problem they seek to address. This post highlights the reasons why narratives hegemonize our minds, this points to twenty-five orthodoxies that persist despite evidence to the contrary, and this argues why the pursuit of development remains a narratives-based faith driven activity.

The FT’s chief data reporter John Burn-Murdoch is a terrific teller of stories using data visualisation. His weekly storiesare brilliant. His latest on the sharp dissonance between the realities of American life and what Americans think about themselves is a good example. This graphic in particular captures the stark reality of American economy and life. The richest country also has the poorest people.

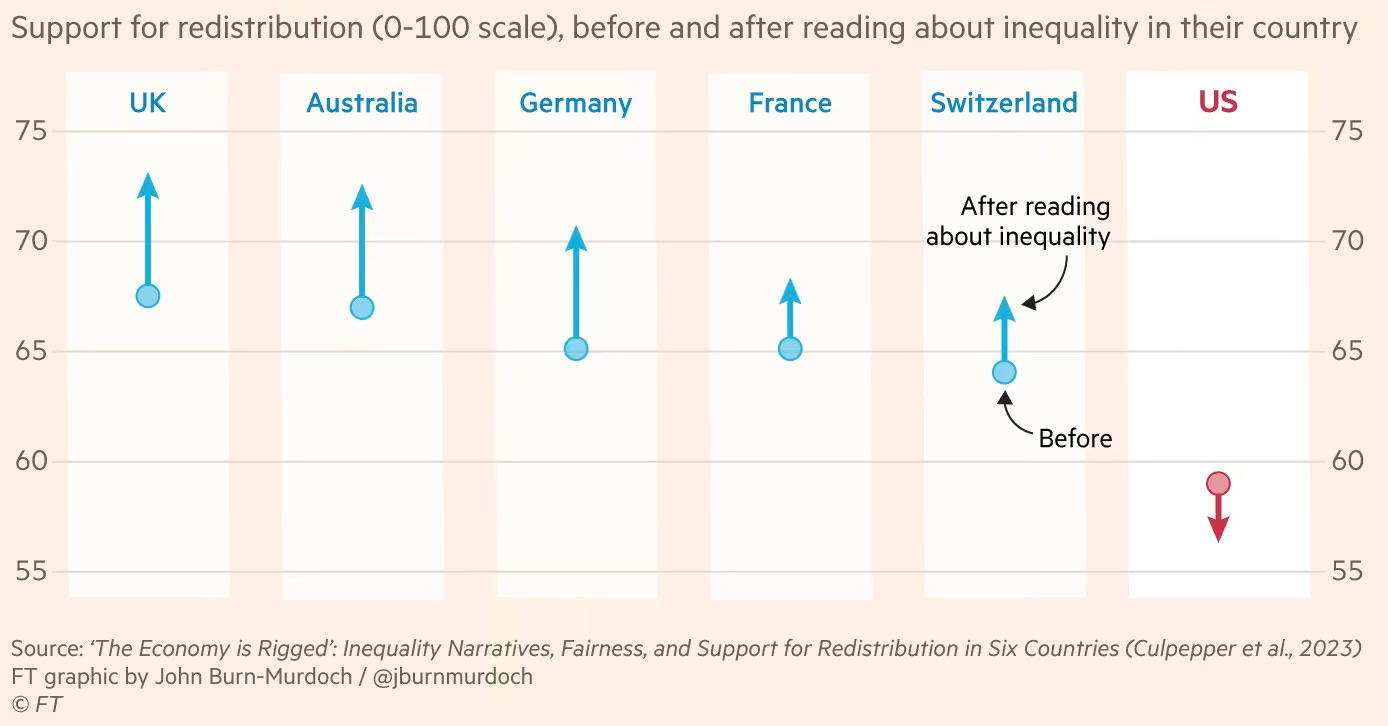

Despite this stark reality, Americans are less supportive of redistribution than people in other western countries. In fact, a new study that primed people to respond to questions after being asked to read stories about the wide national level inequalities appeared to make the even less keen to support redistribution.

The study writes

Drawing on the media effects and political economy literatures, we expect articles employing narratives that portray inequality as the consequence of systemic unfairness to increase demands for redistribution. We test this proposition via an online survey experiment with 7,426 respondents in Australia, France, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Our narrative treatment significantly increases attitudes favoring redistribution in five of the countries. In the US the treatment has no effect.

Burn-Murdoch supplements

While Americans may recognise their country’s problem with inequality, they have less desire for something to be done about it than their counterparts elsewhere in the west. More striking still, being shown how wide national inequalities are has no impact on US desire for the gaps to be narrowed — in fact, if anything it reduces appetite for redistribution. In other western countries that same prompting results in more calls for redistribution… In these countries, people were given a news article that used inequality data to argue that the economic system in their country was rigged. Outside the US, reading the article reliably increased beliefs that society is divided into haves and have-nots, which in turn boosted support for redistribution. In the US, it did neither.

He points to two narratives-shaped cultural reasons for the persistence of these beliefs

The first is what I call the two sides of the American dream. Data show that Americans see themselves as more upwardly mobile than people from other western countries (in reality the inverse is true), and are more likely to say hard work is essential for getting ahead in life. These are aspirational, meritocratic beliefs, but the flip side is that Americans are also the most likely to say low-income people need to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. If Americans view extreme incomes with more aspiration than anger relative to their counterparts in other countries, this could explain reactions to the inequality article. If seeing inequality can equate to seeing opportunity, the American dream makes US society more tolerant of large disparities.

The second dynamic, highlighted by Culpepper and his co-authors, is Americans’ distrust of government, and in particular their belief that government is inefficient. It’s more than 42 years since Ronald Reagan told Americans in his 1981 inauguration speech that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is our problem” — and it appears the nation took his words to heart. While Americans are the most likely to say income inequality in their country is unfair, fewer than half see this as the government’s responsibility to address. This compares with two-thirds or more in the UK, France and Germany. Where other societies see inequality as something that is done to people and must be tackled by helping them, Americans see it as something that people are responsible for themselves.

Narratives shapes culture and political economy, which in turn drives policies. And the narratives often run contrary to evidence. To rephrase a famous saying, narratives eat logic, theory, and evidence for breakfast. These findings on the limits of information awareness and evidence should be reminder to proponents of evidence-based policy making in development.

No comments:

Post a Comment