This blog has consistently argued about the capital deficiency constraints that India faces in its economic growth. I've struggled to come to terms with how a country like India with its acute human and other capital deficiencies can reach a broad-based and sustainable long-term growth trajectory.

The economic orthodoxy and conventional wisdom in economics would have it that countries require a strong capital base - good quality human resources, good infrastructure, large domestic financial savings, state capabilities etc - to achieve high long-term growth rates. India struggles with all these in comparison with China and other North East Asian countries that we want to emulate.

The classic industrial policy involves economy-wide measures like fiscal concessions and subsidies. Such measures run into the problems of the inadequacy of resources to do it meaningfully enough at scale, the fidelity of its national implementation struggles due to weak institutional capabilities, and their political capture by local interests aret very high.

In this context, the idea of attracting large manufacturers in ecosystem creating industries might be a promising strategy to adopt. An example is the Indian government's push for Apple.

Nikkei Asian Review has an article on Apple's thrust to develop India as a manufacturing base for its products.

Apple's suppliers in India... which makes the new iPhone 15 series, are being asked to make over 15 million iPhones in India this year -- more than double the goal a year ago... It is all part of a tectonic shift in Apple's manufacturing supply chains... It once took one year longer to produce a new iPhone in India than in China, but the gap was reduced to around a month in 2022. The target this year is to narrow that to less than 10 days... Expanding production in India is a massive strategic undertaking for Apple, not to mention for the hundreds of companies that make parts for Apple iPhones... For years, China had been the stable bedrock of slick Apple production. More than 80% of Apple's top 188 suppliers have at least one manufacturing facility in China... Meanwhile, China has accounted for more than 95% of global iPhone production since the handset was launched in 2007...But the era of exclusive dependence on China is ending... Earlier in 2023, Apple told suppliers to prepare to build at least 20% of total iPhone annual production in India in the coming years... The proportion currently stands at less than 10%... Rather than snapping together already finished components in India, Apple plans to make more intermediate parts, such as metal casings, in the country... Most important of all, Apple wants to bring crucial new iPhone product development resources to India from China. That involves thousands of engineers and the establishment of numerous new laboratories... Hundreds of suppliers make the roughly 1,500 components that go into an iPhone, and the decisions of these suppliers are crucial to the success of the move. Everything from battery packs, screens, casings and assembly are all done by third parties, who must build new capacity in India or ship their products from elsewhere for assembly if the plan is to succeed. Companies that covet their status as Apple suppliers and are quite used to moving whenever and wherever Apple says... Apple has asked suppliers to keep prices of components made in India the same as those made in China, despite additional logistics and tariff costs. There is also the massive challenge of setting up plants in an unfamiliar environment...Meanwhile, in an effort to cultivate a local supply chain -- a goal encouraged by the Indian government -- Apple began allocating some orders for iPhone metal casing frames, which require precision manufacturing, to Tata. Normally such orders would only go to proven suppliers with years of experience, who have gradually worked their way up... the rise of Tata is in line with Apple's usual strategy to nurture the local supply chain -- as it did in China -- and the Indian company's entry into the Apple supply chain meets New Delhi's ambition to elevate their electronics manufacturing capability, analysts and industry executives say... India wants to attract big global tech titans and their suppliers, and more importantly to nurture national champions to upgrade the value chain and transform the Indian economy...

Apple will allocate the so-called New Product Introduction (NPI) of iPhones to India in the coming years... NPI is the most important part of launching new electronic goods. It involves close collaboration between brands and suppliers, jointly developing a product from the drawing board to the factory with all the testing and verifying that this entails. For more than a decade, iPhone NPIs were done by close cooperation between Apple's research and development team in Cupertino, California, and suppliers' R&D teams in China. Bringing NPI resources to India is a major step in technology development.

India may finally be getting meaningfully integrated with the global manufacturing supply chain that's largely centred around East Asia.

Despite the new interest in India, Vietnam is still the most popular country outside China to build up an electronics supply chain ecosystem, and has so far attracted the bulk of Apple's non-China manufacturing investment. Twenty-five Apple suppliers have already set up production facilities to handle materials, components, modules and assembly. There were only 14 in 2017... The number of suppliers in India grew quickly to 14 by 2022, up from four in 2017, but unlike in Vietnam, they operate at lower levels of technology, manufacturing and assembly, and package components made elsewhere. There are still relatively few component and electronics module makers... Hsu of CIER said it will take India longer than Southeast Asia to build an electronics supply chain. "Tech suppliers took 20 to 25 years to build a mature, complete information technology supply chain in China," Hsu said. "Suppliers also went to Vietnam in the mid-2000s after the country joined the WTO, which is more than 15 years ago. India was not part of the global electronics supply chain before and it only joined it in recent years. The infrastructure is not yet ready, and still needs some time to build."

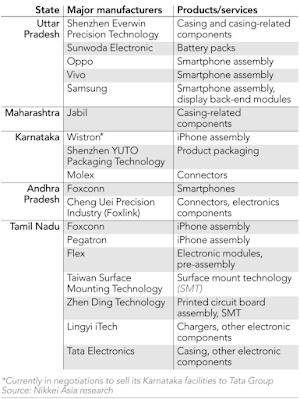

This is a good summary of the mobile phones manufacturing eco-system

One thought here on Apple's Indian foray. The Indian market, especially for such premium products as Apple's, is much smaller than what Apple and others estimate. But the segment below the premium category is large, especially for an aspirational product like the iPhone. Apple will want to capture a major part of this segment. This will require making Apple prices more affordable. Therefore, at some point, Apple will either lower its prices or, more likely, differentiate and come up with lower-cost variants of its products. This will be a first for a company like Apple.

In this context, some observations on industrial policy.

1. There is no doubt that India's ongoing integration with the mobile phone manufacturing supply chain and its emergence as the main competitor to China is an achievement of the government. More needs to be done to move up the value chain, but the success is unmistakable and the trend might have become irreversible. This success can be attributed to the strategy of picking winners and industrial policy. The government should do more of this, albeit carefully.

2. Conventional wisdom would have it governments should not pick winners. India's courting of Apple and mobile phones success is a good example that questions this wisdom. Mobile phones and Apple/Foxconn (and Samsung) are winners. Just as electric vehicles and Tesla, or semiconductor chips and Samsung/TSMC could be. Solar and wind power generation equipment manufacturers and defense manufacturers are another two examples. The same can be said of contract manufacturers Pou Chen, Feng Tay, Hong Fu, Apache, etc in footwear, and Toray, etc in apparel. The facilities of these companies will be large enough to create a manufacturing ecosystem that has transformational impacts in its town or region.

In fact, there's a strong case that instead of spreading resources thin by targeting economy-wide measures like concessions and input subsidies, an outcomes-focused industrial policy for a government would be to identify a few winners (sectors and large brands or contract manufacturers) and court them. Success would be measured by the ability to get one of them to actually make a meaningful enough investment.

The initial investment will invariably be at the lower part of the value chain with components being imported, and local activity being limited to assembly. Industrial policy and government engagement will be essential to create the ecosystem of component suppliers and gradually move up the value chain. This could take several years and would be a genuine success. Governments have to remain engaged to nudge and facilitate this transition. There's the risk of such support being entrapped in an equilibrium of low-value manufacturing.

3. The importance of a large investment in catalysing economic growth is a surprisingly less researched area. Much of the academic research on the development of economic clusters and industrial policy focuses on macro-level measures like special economic zones, plug-and-play facilities, fiscal concessions, and input subsidies.

But large iconic investments offer the clearest pathway to a step change in the industrial capacity and economic fortunes of the region. There are countless examples of such investments transforming the fortunes of regions across the world. In fact, it's the old-fashioned manufacturing story of small towns built around a particular firm.

Such investments bring in their component manufacturers, establish linkages with the wider suppliers network, and provide a solid foundation to build on the value chain. They also lead to learning by doing skills upgradation and technology, and spill-overs of practices and technologies that have large economy-wide productivity improvement impacts.

4. Once these manufacturers become established and start to move up the value chain, it triggers a powerful self-reinforcing dynamic that is strong enough to overcome the typical constraints that hold back manufacturing in India - infrastructure, skilled manpower, poor quality of entrepreneurship, credit for small and medium enterprises, lack of lifestyle facilities, excessive regulations, etc.

Addressing these constraints separately (independent of the anchor company) runs into several co-ordination and financing problems. There's something about the dynamics triggered by the requirements of an emerging ecosystem that aligns incentives and solves the co-ordination and financing problems. This picking-the-big-winners-and-backing-them for an extended period approach stands in contrast to the economic orthodoxy that scorns industrial policy. As discussed in the earlier point, even within industrial policy approaches, this is distinct from the accepted strategy of providing regular industrial policy incentives of subsidies and fiscal concessions.

The education quality deficiency appears less daunting as government skill development programs can effectively link with manufacturer-driven skilling initiatives. The SMEs who are component manufacturers and ancillaries suddenly become credit-worthy enough for banks. Entrepreneurs come forward to offer support services like logistics of transporting workers and/or accommodating. The hotels, restaurants, and other entertainment facilities which otherwise would not have happened emerge. The ecosystem emerges. A wholesale transformation of the region ensues in a few years.

For a country grappling with acute capital deficiencies in terms of poor quality of education, inadequate credit availability, etc, the picking-the-big-winners-and-backing-them for an extended period may be the most effective strategy for manufacturing transformation and good jobs creation.

5. This policy of identifying and pursuing winners has its challenges and risks. Success is critical in picking the right kind of winners in both the industry and the company. Such support can easily get captured by local vested interests and lead to crony capitalism. Success also depends on continuous and active engagement with the identified winners for several years, something that governments with weak capabilities and incentivised primarily to attract new investments generally struggle to do effectively.

The biggest worry is that an industrial policy chasing large investors can end up crowding out the focus on small and medium enterprises that form the basis for economic dynamism, job creation, incremental output expansion, etc. As a comparator, the focus on health insurance has squeezed out spending and attention on public health across governments.

No comments:

Post a Comment