As explained in this note, improvements in transport infrastructure (e.g., the highway network has doubled over the past decade), the introduction of GST (in 2017) and new business models which have migrated from the developed world to India over the past decade, are resulting in India’s 20 largest profit generators earning a staggering 80% of the nation’s profits as compared to around 40% a decade ago. This in turn is leading to an increasingly polarized stock market.

In the decade ending 31st March 2012, the Nifty added around $440 bn in market cap. In these ten years, ~80% of the value generated came from 17 companies and the median Total Shareholder Return (TSR) CAGR was 26% for these 17 companies. Moving forward by a decade, in the decade ending March 31st, 2022, the Nifty added ~$1.4 trillion in market cap. And 80% of the value generated in these ten years came from just 20 companies whose median TSR CAGR was 18%. As the table above shows, wealth creation in India is being driven by a dozen and a half companies. Another way to understand this is to look at the polarisation in Free Cashflows to Equity (FCFE). A decade ago, the top 20 FCFE generating companies in the Nifty (in the decade ending March 2012) accounted for just 23% of India Inc’s FCFE. Moving forward by a decade, if we look at the top 20 FCFE generating companies in the Nifty in the decade ending 31st March 2022, they account for 51% of India Inc’s FCFE.

The list of these companies is below

In a recent paper, former RBI Deputy Governor Viral Acharya used the Prowess data to document a sharp rise in business concentration with industries. The market share of the Top 5 firms by sales has started rising since 2016 after having declined for long.

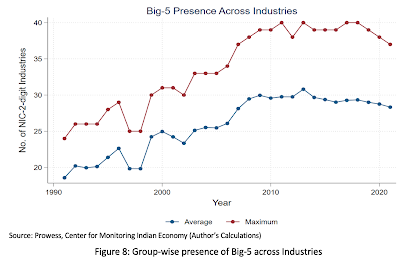

Much the same trend of reversal is observed in case of Top 5 by assetsThis concentration has been especially pronounced among the Big Five corporate groups (Ambani, Tata, Aditya Birla, Adani, and Bharti Telecom). The sales share of the Big 5 have been rising, compared to the declining share of the next five.

The Big Five have been consolidating their presence at the extensive margin (expanding into newer industries)

And also at the intensive margin (deepening their assets share in the already existing industries)

Finally, Ishan Bakshi in the Indian Express documents several duopolies across sectors, mostly foreign owned,

The automobile sector in India is dominated by Maruti Suzuki and Hyundai. Both are foreign-owned. Together, the two account for roughly six out of every 10 cars sold in the country. Add Tata Motors, the biggest Indian auto player, and these three players control almost 70 per cent of the total car market... Three players — Hero MotoCorp, Honda and TVS Motor — account for nearly three-fourths of the total two-wheelers market. Two of these – Hero and TVS – are Indian-owned while Honda is a subsidiary of a Japanese firm... the mobile phone market in India is dominated by the Chinese brands Xiaomi, Vivo and Realme, and the South Korean giant Samsung. Vivo, Realme, Oneplus and Oppo are reportedly linked to the same Chinese company. Together these companies controlled roughly 70 per cent of the market in 2022. The smart TV market is similarly dominated by the likes of Xiaomi, Samsung and LG. Similar patterns can be observed in other consumer appliance markets as well as in various segments of the FMCG market... Indian players exercise more control in the core infrastructure sectors. For instance, in steel, the four biggest companies — JSW Steel, SAIL, Tata Steel and JSPL — control more than half the market... Similarly, the four biggest Indian cement firms command half of the market share in the country...The telecoms sector is dominated by two large players (Jio and Airtel) and a weak third player (Vi) with an uncertain future. Together, Jio and Airtel account for more than two-thirds of the market... The airline industry (domestic travel) is also now dominated by two players — Indigo and Tata (Air India, Vistara, AirAsia India and Air India Express). Taken together, the two airline groups accounted for more than 80 per cent of the domestic market share in the year so far (Jan-Feb). In the private banking space, HDFC, ICICI and AXIS account for a significant share (though all of them have sizeable foreign ownership), while concentration is also evident in airports and ports. Similar patterns can be observed in online markets as well. For instance, the retail market is dominated by Amazon and Flipkart; the payments market has been cornered by PhonePe and Google Pay; food delivery is split between Zomato and Swiggy; and transportation between Ola and Uber. Most of these companies are either foreign-owned or majorly backed by foreign players.

No comments:

Post a Comment