I have blogged earlier about unaffordable housing and traffic congestions being the biggest threat to urban growth.

Take the example of housing. Increasing the stock of affordable housing is arguably one of the biggest public policy challenges. Even when the stock of housing increases, it's often the case that the increase is confined to the supply of higher value units. Worse still, thanks to trends like gentrification and housing increasingly an investment asset in the largest cities, the stock of affordable housing ends up shrinking. Sample this from New York City (via this report),

Between 2017 and 2021, New York City lost almost 100,000 units that had rented for less than $1,500 per month, while it added 107,000 units that rent for at least $2,300 per month... In Manhattan, for example, the median effective rent in April 2022 was $3,870, more than 38 percent higher than a year before and the highest level ever recorded.

One could say that these effects are much more pronounced in rapidly growing cities of the developing world. Rapid growth of the biggest cities have made them pockets of continuing asset bubbles which in turn attract speculative and other investors, thereby pricing out the middle-class and below.

On the transportation side, nearly 160 years after the first metro rail system was launched in London in 1863, the £19 bn Crossrail project connecting the west and east of London became partially operational last week. It's designed to halve journey times and bring the city's four airports together with just one interchange, the Elizabeth Line will bring an additional 1.5 m people to within 45 minus of central London. The project is four years late and £4 bn over budget.

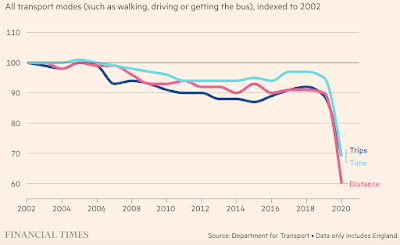

The opening of Crossrail comes at a time when metro rail systems globally are facing a crisis. Passenger growth in metro railways have been stagnant for the last decade and Covid 19 dealt a body-blow. Even after the passing of Covid, commuter traffic is only 60-70% of pre-covid levels. Even more strikingly, overall all transport modes have declined over the last two decades as people have stayed at home.

Between 2002 and 2019, the average distance people in England travelled annually fell by 10 per cent and the number of trips by 11 per cent, according to official UK data. The decline was observed across almost all modes of transport, from short walks to public transport to driving. The trend is similar in Europe and the US, even though it is sometimes masked by population growth. Even before the pandemic, fewer people were commuting the full five days a week, and more employees were on short-term contracts or working in the less routine “gig” economy. This has weakened the economic case for shiny new urban transit projects in those places. Of the 56 new metro systems that opened worldwide between 2010 and 2020, 44 were in the Asia-Pacific region, according to the International Association of Public Transport, and just one was in Europe... The pandemic has accelerated and cemented the shift. Today, more so-called knowledge workers are based at home or in third spaces closer to home, such as cafés or co-working spaces, than ever before... In Greater London, public transport use last week was still down around 33 per cent compared with February 2020 levels, according to Google Mobility data.

While commutes are stable or declining in mature urban systems in developed countries, they're exploding in the rapidly expanding developing country cities. Worsening the problem is the unaffordability of housing, which pushes people out to the suburbs, thereby increasing commute times. In other words, at their prevailing population levels, congestion and commute times increases faster than the urban population growth itself in most major developing country cities.

No comments:

Post a Comment