Adam Tooze points to a world facing a "poly crisis",

A problem becomes a crisis when it challenges our ability to cope and thus threatens our identity. In the polycrisis the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts. At times one feels as if one is losing one’s sense of reality. Is the mighty Mississippi really running dry and threatening to cut off the farms of the Midwest from the world economy? Did the January 6 riots really threaten the US Capitol? Are we really on the point of uncoupling the economies of the west from China? Things that would once have seemed fanciful are now facts... What makes the crises of the past 15 years so disorientating is that it no longer seems plausible to point to a single cause and, by implication, a single fix. Whereas in the 1980s you might still have believed that “the market” would efficiently steer the economy, deliver growth, defuse contentious political issues and win the cold war, who would make the same claim today? It turns out that democracy is fragile. Sustainable development will require contentious industrial policy. And the new cold war between Beijing and Washington is only just getting going. Meanwhile, the diversity of problems is compounded by the growing anxiety that economic and social development are hurtling us towards catastrophic ecological tipping points.

I'm not convinced by the economic (winding down of the monetary accommodation etc), political (threats to democracy), geo-political (new Cold War), social (widening inequality), and medical (pandemics) aspects of the polycrisis. We've been through these and congruently at that. On each of these, one can point to examples of simultaneous and deep crisis over the last hundred years, which have been overcome and societies have flourished. Without being complacent, I am inclined that the over-exposure and over-analysis traits of our present times may be exaggerating the threats of these trends beyond earlier times.

But the environmental challenges are different. Unlike the earlier times, we may be treading the boundaries of irreversible and catastrophic "tipping points". It's not the rise of temperatures or recession of coastlines or the depletion of glaciers or the recurrence of floods, droughts, and wildfires or breakout of pandemics that is the matter of worry. It's the staggering and unprecedented pace of these changes that should worry us. Given that there are thresholds beyond which our eco-systems start to fail, this is indeed a bigger crisis than any of the ones that modern humanity has encountered.

What makes the problem deadly is that any solution involves fundamental and significant changes to our current livelihoods and lifestyles. And the extent of adjustments will be inversely proportional to people's wealth. It's fundamentally about asking the elites and well-off to adjust downwards their expectations and consumption. The developed economies should be satisfied growing at 1-2% and developing countries at 5%. We need an Age of Great Moderation. Try telling this to them.

It's actually even more difficult. Human beings are collectively wired towards expanding the boundaries of knowledge and increasing prosperity. The central thesis of western philosophy is progress. Consider the ongoing debates on the Great Stagnation, even as human beings enjoy the quality of life which would have been unimaginable for those living even forty years back. The lament about Great Stagnation while surprising given the quality of life enjoyed by people today is also understandable given our insatiable hunger for continuing improvements in human condition.

Upending this norm is the biggest challenge. Societies, like individuals, accept deep changes only when it's forced on them. But by then it's too late to salvage the situation, in case of irreversible catastrophic changes like climate change. It's for this reason that the long history of humanity is recurrent with cycles of growth and disappearance of civilisations and populations. It remains to be seen how likely will we be able to avoid this trend.

This is not case for freezing progress, but instead looking at progress in more holistic, equitable, and sustainable terms. For a start, it's worth keeping in mind that there is nothing to support the belief that economic growth of this generation and a couple earlier is the natural order of things. It is well-acknowledged that the growth spurt since the late nineteenth-century has not only been unprecedented but also outside the norm for centuries of human existence, and there is therefore nothing to suggest that it should continue.

It's also about eschewing the current benchmarks of progress which is focused on income growth, greater convenience, greater efficiency, and constant and rapid innovation. In any physical system, there is a limit to how much can be extracted out of it. The same is true of earth too, and there are enough signs that we may be at those limits, if not already exceeded it. Similarly, some degree of physical labour, inconvenience, stress, pain and slack may be essential to ensure that individuals and societies learn, remain vigilant, and retain the capacity to protect what we often take for granted. In this context, this commencement speech by Robert Foster Wallace is a must watch. There is a case that the quest for convenience and efficiency has reached a stage of damaging returns.

So what would be an alternative path to progress?

Reversing some of the damages that have been inflicted and ensuring that we get back to within the sustainable boundaries should become the top priority. This should be a collective commitment of humanity. And given the importance of leadership, it's imperative that the elites and rulers assume this role. While there is policy engagement, this is more about reshaping expectations and adjusting and changing lifestyles. It's also about formulating a new purpose of life, which goes beyond the purely material and reductionist modern western philosophy and embracing the Eastern and classical philosophies.

Besides, it's undeniable that we a problem of poverty, which is an issue of development and redistribution. This should become the single biggest public policy challenge. It's a shame that we live in societies, all of which have shameful excesses of plenitude co-existing with acute deprivation. This, along with improving the quality of progress, should be the policy endeavour. The objective function of progress should incorporate resilience, sustainability, fairness, equity, and political aspirations, in the place of efficiency. The application of innovation and entrepreneurial energies should be focused on these paths of progress.

In a model, the current version of Progress can be defined as

P (Now) = f (GDP, efficiency)

The alternative version would be

P (Alternative) = f (GDP, resilience, sustainability, fairness, equity, political demands)

Simon Kuper has an article which points to the possibility of Netherlands being possibly the first country to hit the limits to growth.

Update 1 (06.11.2022)

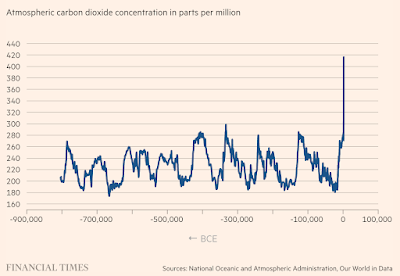

Martin Wolf has two graphics which highlight the enormity of the environmental changes confronting us. The first shows the alarming rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide, to the highest levels ever and rising steeply.

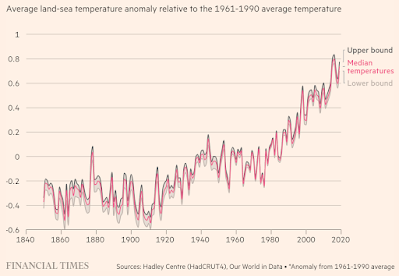

The second refers to the rise in average land-sea temperature difference.

There are irreversible tipping points which are being crossed.