Gillian Tett points to an insightful

presentation by BIS Chief Economist Hyun Song Shin which explores the reasons for the current global economic slowdown. Shin starts off by describing the changes in global value chains (GVCs), which along with MNCs underpinned the current wave of globalisation and growth in trade, especially with the arrival of China.

The snapshot of network structure of goods and services trade in 2000 and 2017, where the hub-and-spokes link two economies if one is the largest trading partner of the other or if one accounts for more than 25% of the trade for the other, is illuminating.

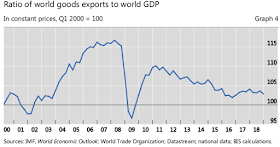

China's emergence as a hub and as connector between Germany and the US is remarkable. Shin then points to the trends in gross exports to GDP ratio, the numerator of which increases with complexity of GVCs since they generate multiple export sales of intermediate goods, all of which add up. It rose 16% from 2001 to 2008 as GVCs exploded in complexity, only to collapse during the Great Recession and has since 2010, pre-dating the current protectionist trend, been on a secular decline.

Clearly, just as the GVC activity boosted global trade in the noughties, its unravelling has pulled down trade this decade.

While the growing share of services in global trade and technological innovation like automation making in-shoring more cost-effective are important contributors to the current secular decline, Shin point to another intriguing possibility, finance. He writes, pointing to an uncanny resemblance of the graph above to the global banking cycle,

Building and sustaining GVCs are highly finance-intensive activities that make heavy demands on the working capital resources of firms. When the financial requirements go beyond the firm’s own resources, the necessary working capital is dependent on short-term bank credit. The financing requirement for GVCs arises because firms need to carry inventories of intermediate goods or carry accounts receivable on their balance sheet when selling to other firms along the supply chain... As supply chains grow longer and the time period between shipments becomes more extended, the marginal financing needs grow at an ever increasing rate, so that very long GVCs are viable only with very accommodative financing conditions.

If you will excuse a colourful metaphor, firms enmeshed in global value chains could be compared to jugglers with many balls in the air at the same time. Long and intricate GVCs have many balls in the air, necessitating greater financial resources to knit the production process together. More accommodative financial conditions then act like weaker gravity for the juggler, who can throw many more balls into the air, including large balls that represent intermediate goods with large embedded value. However, when the shadow price of credit rises, the juggler has a more difficult time keeping all the balls in the air at once.

When financial conditions tighten, very long and elaborate GVCs will no longer be viable economically. A rationalisation of supply chains through “on-shoring” and “re-shoring” of activity towards domestic suppliers, or to suppliers that are closer geographically, will help reduce the credit costs of supporting long GVCs. In its 2014... around 35% of trade was financed by the banking system. The rest – around 65% – was financed by the firms themselves, either by the seller in the form of “open account financing” or by the buyer paying upfront in a “cash-in-advance” purchase. Crucially, the CGFS found that around 80% of bank trade financing was denominated in US dollars, reflecting the prevalence of dollar invoicing in world trade... Among the many indicators of the availability of dollar- denominated bank credit, the dollar exchange rate plays a particularly important role as a barometer of the dollar credit conditions faced by firms. Lending in dollars tends to grow faster when the dollar is weak, and lending in dollars is subdued or declines when the dollar is strong... When combined with the fact that GVC activity tracks dollar financing conditions, the upshot is that the fluctuations in the trade-to-GDP ratio plotted in Graph 4 closely track the strength of the dollar, with a stronger dollar associated with subdued GVC activity... During periods when the dollar is strong, trade is low relative to GDP. During periods when the dollar is weak, trade is high relative to GDP.

He also argues that this inter-twined nature of finance and trade could explain the persistence of the strength of the dollar despite the monetary accommodation in the US,

The relationship between financial conditions and the dollar will reflect many forces operating in the economy, but among these may be balance sheet channels involving non-financial firms that are linked through GVCs. Strong corporate balance sheets enable firms to meet the heavy working capital needs of being part of GVCs. However, higher corporate debt combined with currency mismatches on the firm’s balance sheet can undermine the firm’s ability to finance working capital, especially when credit conditions tighten. Firms weighed down by currency mismatches and excessive leverage will need to reduce debt and rebuild capital. Globally, high corporate leverage has emerged as a source of vulnerability for growth. Corporate leverage has remained high even as profitability has declined sharply in some jurisdictions, such as China and especially among small and medium-sized enterprises in the manufacturing sector. Within this broad context, the continuing strength of the dollar may reflect, in part, efforts at balance sheet repair by such firms. A stronger dollar would increase the urgency of balance sheet repair, as it would sharpen the incentives to repay dollar debt. Perhaps for this reason, recent moves in the currency market have overturned the usual rule of thumb that looser monetary policy in the United States is associated with a weaker dollar. The dollar has remained strong, especially against emerging market currencies.

Trade rose rapidly within nearly all global value chains from 1995 to 2007. More recently, trade intensity (that is, the ratio of gross exports to gross output) in almost all goods-producing value chains has fallen. Trade is still growing in absolute terms, but the share of output moving across the world’s borders has fallen from 28.1 percent in 2007 to 22.5 percent in 2017... The decline in trade intensity is especially pronounced in the most complex and highly traded value chains... In 2017, gross trade in services totaled $5.1 trillion, a figure dwarfed by the $17.3 trillion global goods trade. But trade in services has grown more than 60 percent faster than goods trade over the past decade. Some subsectors, including telecom and IT services, business services, and intellectual property charges, are growing two to three times faster... counter to popular perceptions, today only 18 percent of goods trade is based on labor-cost arbitrage (defined as exports from countries whose GDP per capita is one-fifth or less than that of the importing country)... Moreover, the share of trade based on labor-cost arbitrage has been declining in some value chains, especially labor-intensive goods manufacturing (where it dropped from 55 percent in 2005 to 43 percent in 2017)... In all value chains, capitalized spending on R&D and intangible assets such as brands, software, and intellectual property (IP) is growing as a share of revenue. Overall, it rose from 5.4 percent of revenue in 2000 to 13.1 percent in 2016... The share of trade in goods between countries within the same region (as opposed to trade between more far-flung buyers and sellers) declined from 51 percent in 2000 to 45 percent in 2012. That trend has begun to reverse in recent years. The intraregional share of global goods trade has increased by 2.7 percentage points since 2013, partially reflecting the rise of emerging-market consumption... Regionalization is most apparent in global innovations value chains, given their need to closely integrate many suppliers for just-in-time sequencing.

As to the drivers of these trends,

The map of global demand, once heavily tilted toward advanced economies, is being redrawn—and value chains are reconfiguring as companies decide how to compete in the many major consumer markets that are now dotted worldwide... By 2030, developing countries are projected to account for more than half of all global consumption... The biggest wave of growth has been happening in China... by 2030, they are projected to account for 12 cents of every $1 of worldwide urban consumption... In 2016, 40 percent more cars were sold in China than in all of Europe, and China also accounts for 40 percent of global textiles and apparel consumption... Within the industry value chains we studied, China exported 17 percent of what it produced in 2007. By 2017, the share of exports was down to 9 percent. This is on a par with the share in the United States but is far lower than the shares in Germany (34 percent), South Korea (28 percent), and Japan (14 percent)... In 2002, India, for example, exported 35 percent of its final output in apparel, but by 2017, that share had fallen by half, to 17 percent, as Indian consumers stepped up purchases... The rise of domestic supply chains in China and other emerging economies has also decreased global trade intensity... As a group, emerging Asia has become less reliant on imported intermediate inputs for the production of goods than the rest of the developing world (8.3 percent versus 15.1 percent in 2017)... The decline in trade intensity reflects growing industrial maturity in emerging economies. Over time, their production capabilities and consumption are gradually converging with those of advanced economies... New technologies are changing costs across global value chains... Instant and low-cost digital communication has had one clear effect: lowering transaction costs and enabling more trade flows... the next wave of technology could dampen global goods trade while continuing to fuel service flows...

In goods-producing value chains, logistics costs can be substantial. Companies often lose time and money to customs processing or delays in international payments. Three sets of technologies will continue to reduce these frictions in the years ahead. Digital platforms can bring together far-flung participants, making cross-border search and coordination more efficient. E-commerce marketplaces have already enabled significant cross-border flows by aggregating huge selections and making pricing and comparisons more transparent... Logistics technologies also continue to improve. The IoT can make delivery services more efficient by tracking shipments in real time, and AI can route trucks based on current road conditions. Automated document processing can speed goods through customs. At ports, autonomous vehicles can unload, stack, and reload containers faster and with fewer errors. Blockchain shipping solutions can reduce transit times and speed payments. We calculate that new logistics technologies could reduce shipping and customs processing times by 16 to 28 percent...

Automation and additive manufacturing change production processes and the relative importance of inputs... The growing adoption of automation and advanced robotics in manufacturing makes proximity to consumer markets, access to resources, workforce skills, and infrastructure quality assume more importance as companies decide where to produce goods. Service processes can also be automated by artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual agents. The addition of machine learning to these virtual assistants means they can perform a growing range of tasks. Companies in advanced economies are already automating some customer support services rather than offshoring them. This could reduce the $160 billion global market for business process outsourcing (BPO), now one of the most heavily traded service sectors... Overall, we estimate that automation, AI, and additive manufacturing could reduce global goods trade by up to 10 percent by 2030, as compared to the baseline...

New goods and services enabled by technology will impact trade flows. Technology can transform some products and services, altering the content and volume of trade flows in the process. For example, McKinsey’s automotive practice estimates that electric vehicles will make up some 17 percent of total car sales globally by 2030, up from 1 percent in 2017. This could reduce trade in vehicle parts by up to 10 percent (since EVs have many fewer moving parts than traditional models) while also dampening oil imports. The shift from physical to digital flows that started years ago with individual movies, albums, and games is now evolving once again with streaming and subscription models... The advent of ultra-fast 5G wireless networks opens new possibilities for delivering services. Remote surgery, for example, may become more viable as networks transmit sharp images without any delays and robots respond more precisely to remote manipulation. In industrial plants, 5G can support augmented and virtual reality–based maintenance from remote locations, creating new service and data flows.

The biggest declines in trade intensity were observed in the most heavily traded and complex gvcs, such as those in clothing, cars and electronics... talking to many firms in three industries reveals different patterns of fragmentation. The clothing sector is globally footloose; the car industry is coalescing around regional hubs; and the electronics business remains rooted in China.

This about the challenges facing India's ability to benefit from the disruption to GVCs caused by President Trump's actions on China is illuminating,

Mr Trump’s tariffs on China have pushed Big Auto’s supply chains to become even more regional. “We’re finally ready to leave China,” says a senior supply-chain executive at a global car maker. His firm is looking seriously at shifting its sourcing for the global market from China to India, but finds Indian vendors “unreliable”. It thought about dividing between India and Mexico, but saw that its supply base would lose economies of scale. The winner will be Mexico, he says.

This is a fascinating examination of how innovations by Amazon and Alibaba are contributing to shortening and expediting the GVCs,

China is leapfrogging from ropey logistics to supercharged supply chains, just as it did with e-commerce and mobile payments, in which it went from laggard to world-beater... Amazon leads in the use of ai-powered robots in logistics, but China’s entrepreneurs have the edge in speed. Mainland innovators are capable of cutting-edge inventions, for example in facial-recognition software. However, they are also good at frugal engineering, throwing together cheap solutions that can get to market faster than the gold-plated ones favoured by Western innovators.