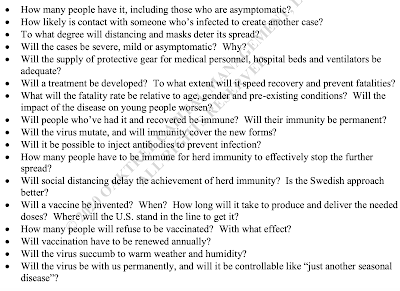

Then there is the sheer complexity of the challenge at hand. To understand it, consider the following set of questions that Howard Marks posed in the context of the emerging SARS Cov 2 pandemic in May 2020.

Who can respond to this many questions, come up with valid answers, consider their interaction, appropriately weight the various considerations on the basis of their importance, and process them for a useful conclusion regarding the virus’s impact? It would take an exceptional mind to deal with all these factors simultaneously and reach a better conclusion than most other people.

He writes about the challenge of making forecasts in the face of uncertainty, and the skills required to be able to make good judgements. This is not about some rote application of technical knowledge. When faced with decision that need to balance several strands of considerations and requirements, it's more an exercise in trying to make practical judgements. That's the realm of public policy and not technical expertise.

As a physician, I was trained first and foremost to think of the individual in front of me… Physicians tend to be conservative in their practice of medicine. We fear a bad outcome disproportionately and will do almost anything to prevent it… But blown to the scale of a whole country, that kind of focus on individuals has often led us in the wrong direction during the pandemic. Much of my frustration at the response to Covid is that too many officials in senior positions at the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention seem to be thinking this way — if something isn’t close to perfect or doesn’t maximize the safety of each individual person, it’s not worth it at all.

For example, a focus on doing the “best” for the individual leads to a belief that if you’re going to test people for the coronavirus, the tests used must be of the highest quality, and that’s a professionally collected PCR, even if those tests are harder to perform and supplies are limited. Focusing on the individual can also lead to excessive fears of bad outcomes, even if they’re rare. Leaders can come to think that any risk of infections is unacceptable, leading to policies that close schools even though the danger that schools appear to pose is low.

A population-level view, on the other hand, often focuses on reaching as many people as possible rather than perfection. This view argues that repeated and regular testing is preferable, and that’s more easily done with tests taken at home even if they’re less sensitive than P.C.R.s in some ways. That the F.D.A. and the C.D.C. have trouble recognizing the utility of at-home tests as a public health tool, as opposed to purely a clinically diagnostic one, shows the shortfalls of always seeking the best. More frequent imperfect testing may pick up more cases, even if we miss a few we might have caught with perfect tests. Getting many people to be somewhat safer might achieve more than getting fewer people to be really safe.

Just this week, my own state, Indiana, made a decision through an individual lens and not a population one. We are running short on rapid antigen tests at state-run sites. The state therefore chose not to use them at all for adults ages 19 to 49. Instead, they’re prioritized for those 50 and above as well as children, and patients have to be symptomatic to get a test.From a clinical lens, this makes sense. You want to save the tests for those at highest risk. Most younger adults will be fine, while older, sicker people might need more attention. But from a population lens, this is the absolutely wrong choice. A test does not prevent you from getting Covid; it gives you the information you need to avoid spreading it. Young people may be at low risk individually, but they’re a big risk to others because they often go out and interact with people. Rapid tests are ideal for them.

The third one is about masks,

If you can have only the best, you’ll focus on N95 masks, see they are in short supply at the start of the crisis and tell most people they shouldn’t wear masks at all because only certain ones provide the best protection, and we have to save them for those at highest risk. A population-level view argues that cloth or surgical masks — which aren’t anywhere near as good as N95s but were easier to get — would lower the risk for everyone when the pandemic was beginning, and therefore would be helpful. It took until April 2020 — many weeks into the pandemic — for the C.D.C. to recommend mask wearing for the general public.

The point of all these is to provide the perspective on expert knowledge and public policy.

This blog came to the view very early on in the pandemic that much of the debates and narratives around Covid are consciously or unwittingly being framed around the works of narrow expertise and powerful interest groups. And they are deceptive or plain wrong or dangerously misleading. Worse still, the veneer of respectability around these opinions and advisories means that they crowd-out even common-sense. Any practical suggestion, based on exercise of judgement, is decried and stigmatised.

Given all the above, a simple response to the pandemic going forward could be - enforce masking, prioritise vaccination (including boosters), continue normal testing, maintain surveillance and limit large gatherings based on any increase in case trends, and get back to normalcy in life. And especially important is to not close down schools since the one lasting legacy of the pandemic is most likely to be the irretrievable loss of learning years with its consequences on economic output for a cohort of learners. Note that this blog had said much the same as early as March 30, 2020. While elements of this response are grounded on firm evidence, the response as a whole is an exercise of practical judgement.

On closely related notes, I have blogged earlier on the "smartness" dominance in development debates, the distinction between being smart and wise, the twin tyrannies of quantitative methods and expert wisdom, challenge of marrying experiential and evidentiary knowledge, the ideology of evidence-based policy making, marginalisation of priors and elevation of evidence generation in policy making, and the trend of ahistoricism and data analytics in economics.

No comments:

Post a Comment